There’s an intersection of art and science in his work. Bright, interwoven geometric patterns in primary colors revealing flashes of Mondrian and Morisson. For a moment, you imagine the patterns look like the building blocks of DNA and wonder if he did, too.

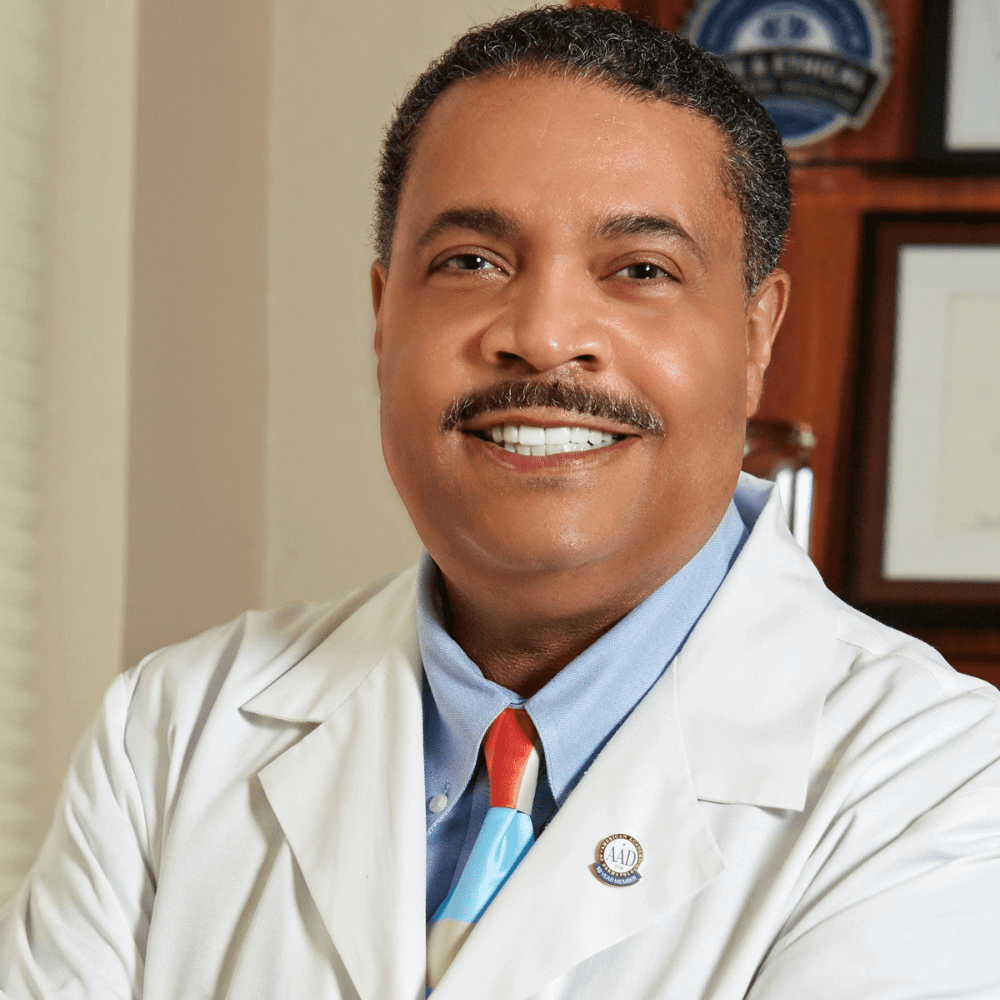

Art inspired Charles Crutchfield when he was in medical school. He walked the halls at the Mayo Clinic as a molecular biology student, taking in the institution’s world-class collection of artwork. He absorbed the abstract shapes and colors of Ellsworth Kelly and the bold, matador-like brush strokes and slashes in black and red by Spanish painter Joan Miró. During what little free time he had between books, hospital rounds and sleeping, Crutchfield painted.

Photography provided by Laurie Crutchfield

“He never had any formal training,” says his wife, Laurie. “He talked about art as a way to escape.” It proved to be vital. Charles had the insight to use art to think abstractly about medicine, pulling apart difficult words and re-envisioning them in the form of an elemental table of letters. Creativity helped him understand that words could be broken apart and reconstituted into sounds, something most people with dyslexia, like himself, can’t do.

That unique way of learning gave Charles the ability to break apart and solve issues within the largest, most complex organ in the human body: the skin. Skin not only protects us from what’s inside of us but also provides a barrier against the world around us. Charles could quickly analyze and give solutions to patients who had been looking for answers for years, like why our immune system creates psoriasis. His weekly news column tackled the cultural flash point of skin bleaching creams in the Black community and helped people rebuild their self-esteem after years of suffering from acne scars and cysts.

His work was featured in more than 100 scientific and educational publications, and he received awards from the American Academy of Dermatology and the Mayo Clinic. Charles was recognized as one of the nation’s leading authorities on skin of color and among the top 100 African American Newsmakers in the United States, per NBC News’ The Grio. And the list goes on: best doctor for women, America’s top dermatologist and more. He was even an expert consultant for CNN’s Sanjay Gupta, MD.

He also discovered that art created a level of empathy within him that connected him closely to his patients and the Twin Cities community in which he grew up. Charles wasn’t just interested in dermatology; he wanted to touch what was under the skin — what makes us feel happiness and sadness. What makes us family. And how we tap into the best inside us. “He spent so much time studying faces in his clinic work,” says Laurie. “He related that to the artwork he created.”

Charles wanted to peel back the sepia-colored images of Black history and give it life. More than simply pages of a book, it was about creating artwork that would make names and faces real for new generations. Fascinated with America’s Negro League players, he pored over faded pictures of obscure athletes — men and a few women who would never be as well known as Jackie Robinson or Willie Mays. Charles researched the colors of their uniforms, eyes and skin tones. He worked with other artists on broad strokes and details. The result was 200 paintings — all shown to the public at the St. Paul Saints baseball field with plans to exhibit them at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, and the Jackie Robinson Museum in New York City.

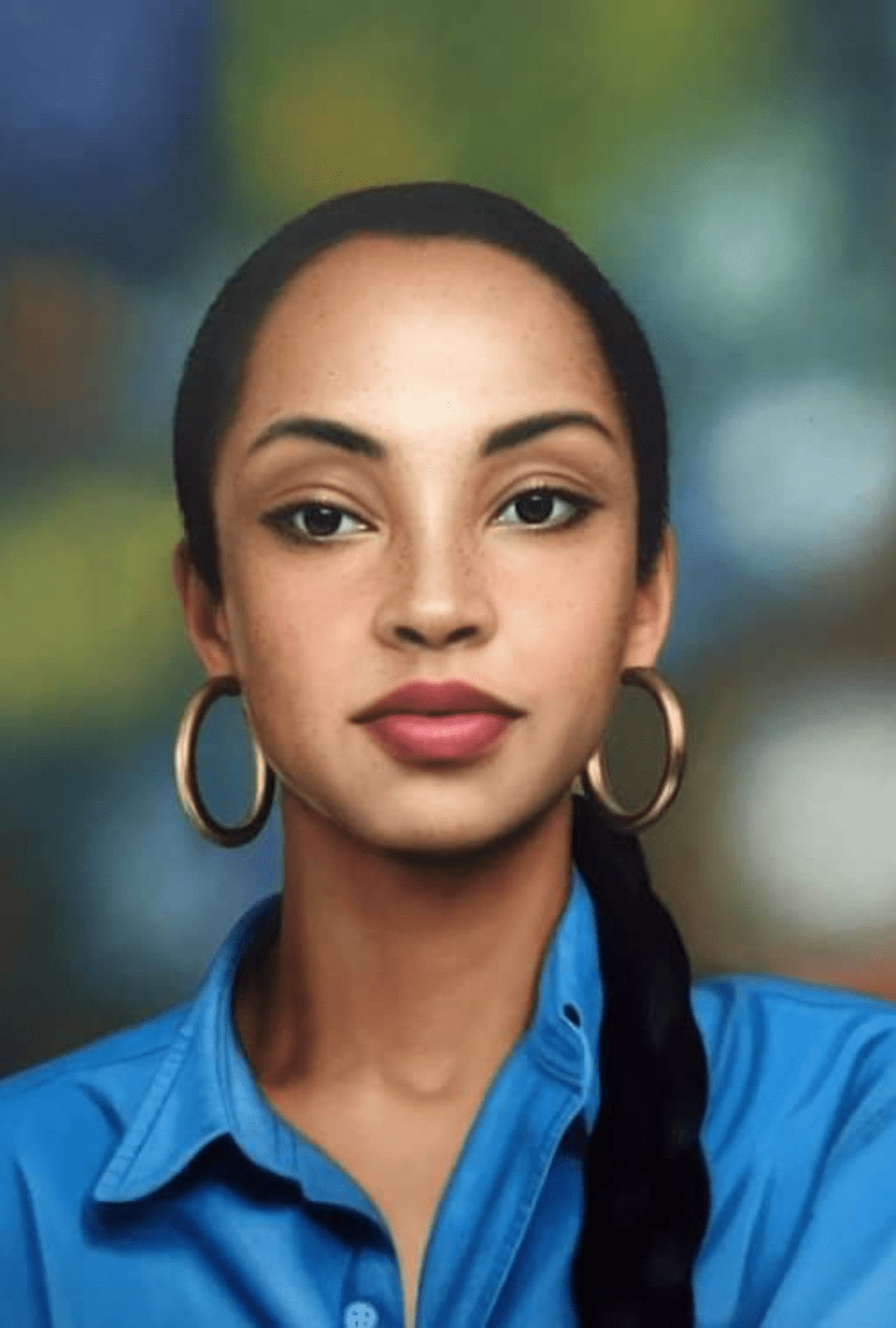

Laurie says that’s when Charles “branched off” with his Icon series: saturated, hauntingly real portraits of notable figures ranging from Frederick Douglass to Sade — each image striking for its obsessive attention to light, wardrobe and skin tone. “There are at least 20 or 30 of them,” she says. “Charles had them framed and gave many of them to relatives and friends.”

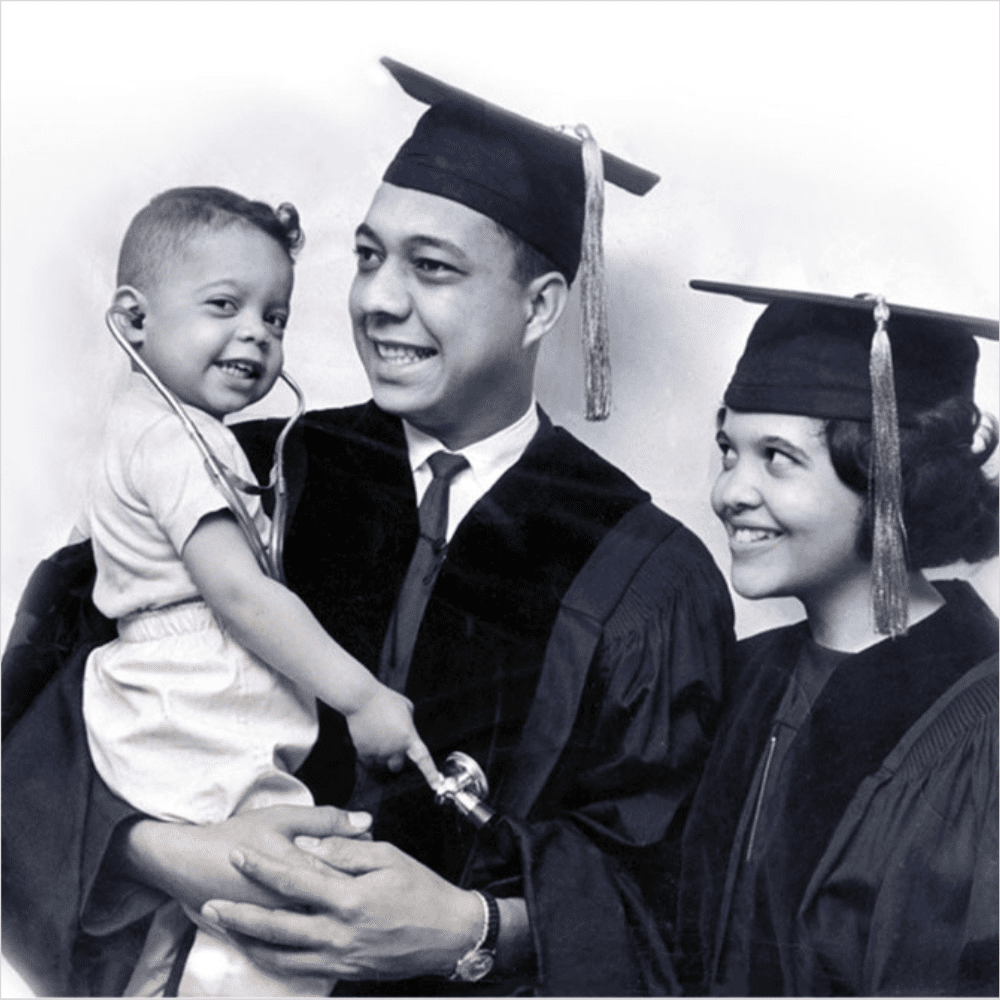

But Charles’ generosity went far beyond giving art away to family members and school pals. Like his pioneering parents (both his mother and father were known for their firsts as Black doctors in the Twin Cities), he was one of the nation’s top authorities on treating skin of color. He provided medical care for children with severe skin trauma so they could safely go to camp. He created a foundation for ethical aesthetic medicine and supported immersive community programs for disadvantaged teens, prompting them to discover new opportunities through music and visual arts. A prolific writer, he even penned a children’s book. Never one to stop creating, Charles had just finished developing a dermatology smartphone app and was working on new projects until the end of his life. He was the true definition of an artist, expressing his creativity both in the clinic and on canvas.