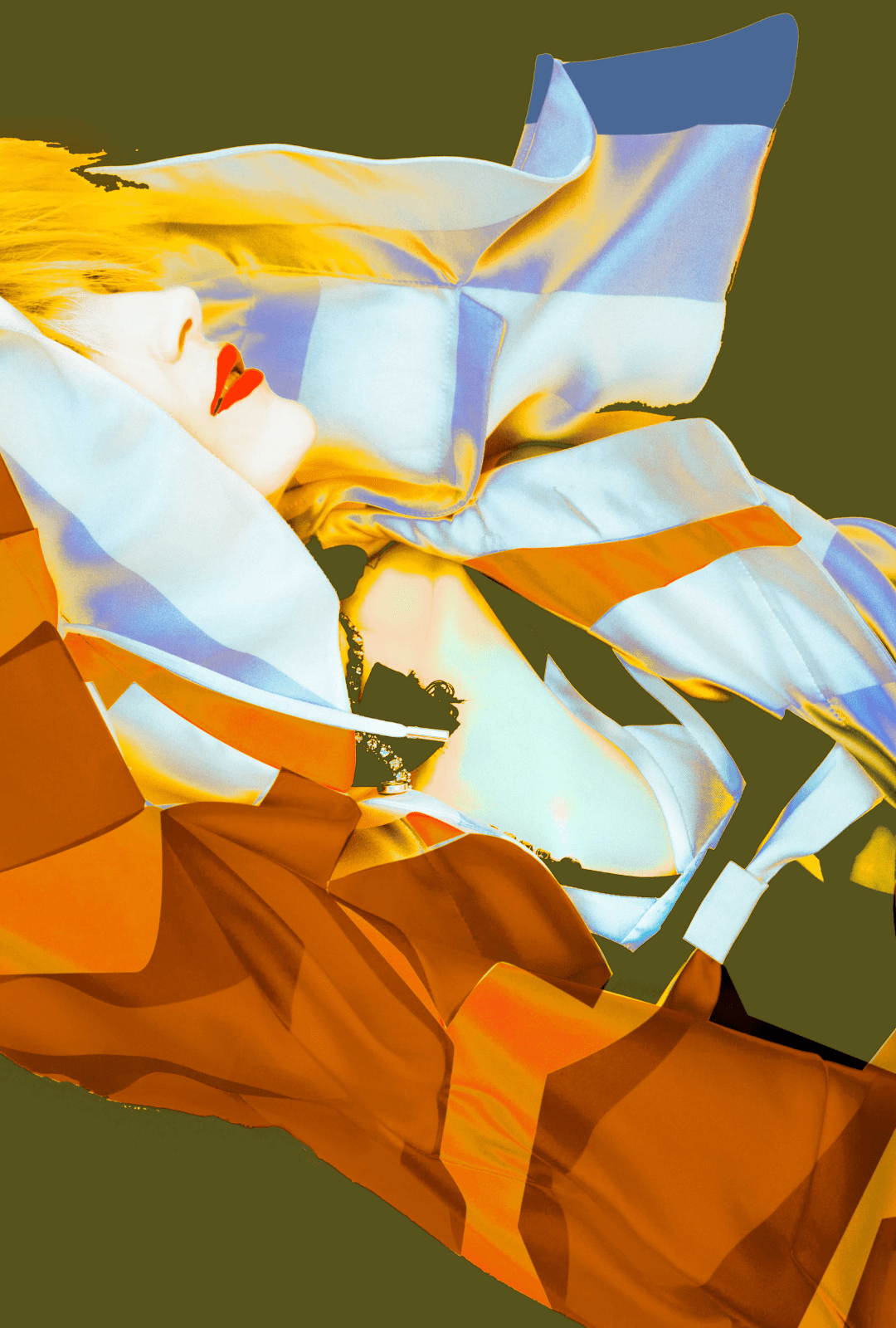

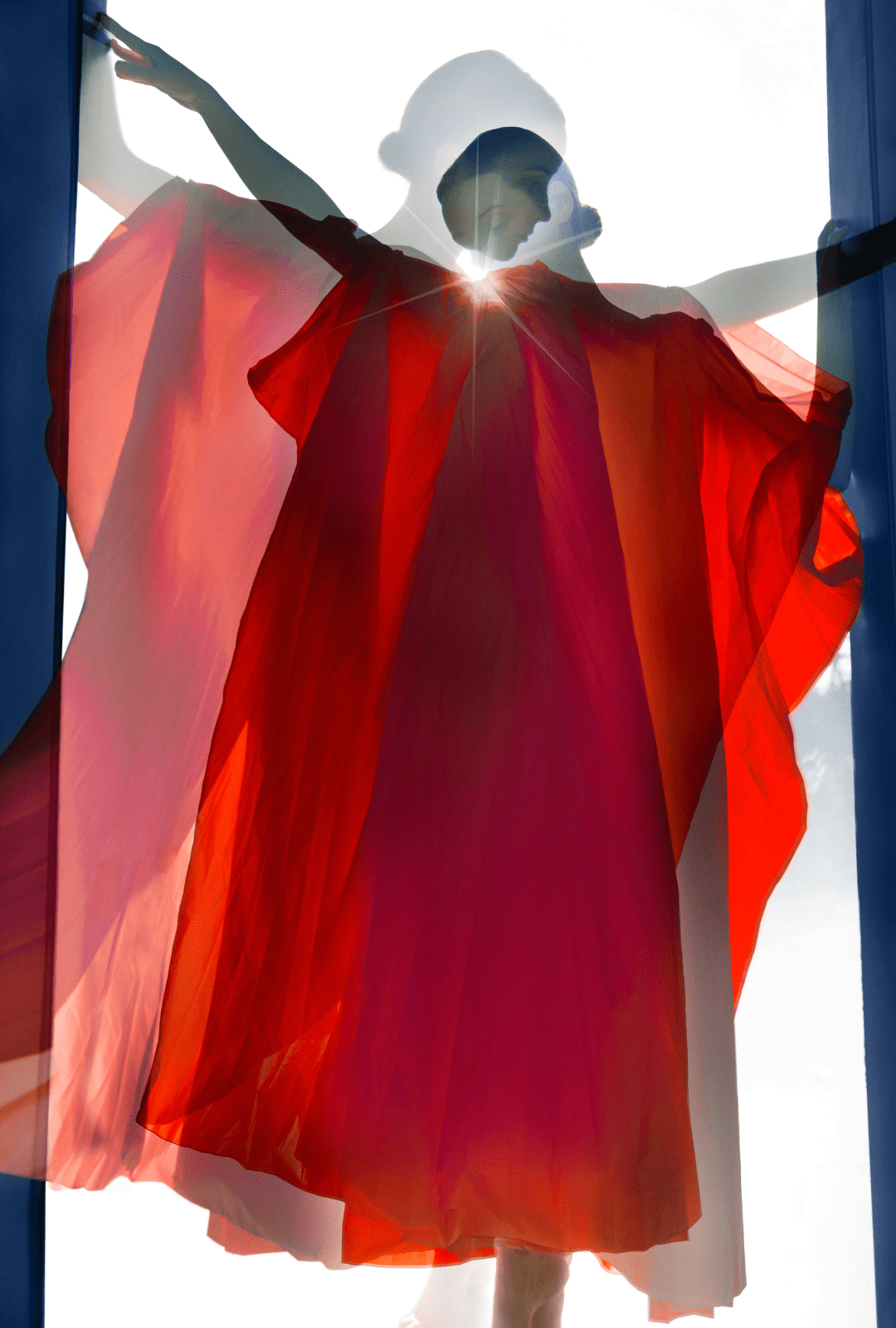

Step into Erik Madigan Heck’s ethereal realm and you’ll be in a world of pure imagination. Born and raised in the Twin Cities, the famed photographer is regularly called upon by the world’s top fashion houses and magazines — the likes of Valentino, Carolina Herrera and Comme des Garçons as well as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar — to craft his signature fantasy worlds. He has been tapped by commercial clients including Nike, Levi’s and BMW, and in 2012 became the youngest creative to shoot Neiman Marcus’ iconic Art of Fashion campaign. His work has been displayed the world over, including at Minneapolis’s own Weinstein Hammons Gallery. Considered one of the most innovative artists in contemporary photography, he has received accolades including a Forbes 30 Under 30 nod, an International Center of Photography Infinity Award, a FOAM Fotografiemuseum talent award and an Art Directors Club gold medal. And rightly so.

Heck’s love of art started at an early age, with his late painter mom and his avid collector dad ensuring he had a steady diet of creative pursuits, including weekly visits to the Minneapolis Institute of Art and Walker Art Center. “I had a very idyllic childhood splitting my time between Excelsior, a tiny village, and Edina, a very affluent white suburb,” says the 40-year-old artist. “My mom taught me how to paint, and my dad collects Papua New Guinea art, so I grew up surrounded by all these tiny statues, shields and spears.” These days, he calls rural Connecticut home but spends much of his time working in London and Paris.

It was during high school at Benilde-St. Margaret’s that he delved into the world of photography. Newly equipped with a 35-millimeter Canon EOS 630 gifted by his mom — the same lens he uses to this day — he established his first aesthetic: moody black and white. The reasoning?

“I was very conservative with how I thought art needed to be and had a very classical sense of what photography was,” he explains. “When you study photography, you start at the beginning with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Edward S. Curtis, and all the early pioneers of black and white. Then you get to the sixties, with William Eggleston and others introducing color photography as art photography. No one had really made color photography great that I could see. Around the time I got into photography, digital photography was just starting, but it looked awful. The only manipulation you could do was these really crass levels that created really bad art. So I decided I was going to be a purist and only do black and white.”

Indeed, the deep appreciation for art history that influenced him in the very beginning still informs his work today. “When you look at art history, everything that came after the late 1800s has had a shelf life,” he notes. “Painting and sculpture are the only mediums that will never stop; they are always changing and are just as relevant as they were 400 years ago. Everything else has a very finite timeline. Black-and-white photography ended in the sixties. Color film photography ended in the late nineties. Digital photography ended a year ago with AI. It’s just an acknowledgement that when you start using a medium that’s dead, your work can only be based in nostalgia. At this stage, I’m more interested in what comes next as opposed to looking backward. I’m super fascinated by AI and what that’s going to do to digital photography.” (More on AI later.)

Before Heck zeroed in on photography, his teenage creative interests ranged from music to fashion to digital art (and he still dabbles in multiple mediums to this day). “If I were to make a hierarchy of art mediums, music has always been my No. 1 thing,” he says. “But I’m not an inherently talented musician. As a teen, I DJed a lot and spent all my money on records; I wanted to be a hip-hop producer.”

His dad’s house in Excelsior was just minutes from Prince’s Paisley Park, yet Heck didn’t listen to the Purple One’s storied songs until after he’d left the Twin Cities. “He’s obviously a legend, but I didn’t grow up worshiping him like a lot of my friends did,” he explains. “Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis were also legends who were pretty underappreciated; a lot of people didn’t know they produced Janet Jackson and a whole bunch of amazing tracks. When I grew up, we had a lot of hometown heroes who were appreciated elsewhere much more than they were in Minneapolis.”

He was equally fascinated by fashion. “I was in high school in 1998 to 2002, which was arguably the peak of avant-garde fashion,” he shares. “You had Belgian designers like Ann Demeulemeester, Martin Margiela and Dries Van Noten and Japanese designers like Yohji Yamamoto. As a kid coming of age in Minneapolis, fashion let me connect with the rest of the world, because it was truly the stage for the world coming together in a very avant-garde, punk rock way. It was still really underground, so as a 14-year-old studying fashion, I sort of felt like I was in a secret club. And I wanted to be a part of that world.”

After staying true to his black-and-white approach for nearly a decade, Heck’s viewpoint began to broaden upon moving to Paris in his early twenties. “When I was there, I started shooting 8-by-10-inch Polaroids, and that’s when I started dabbling in color,” he recalls. “By that point, I had put in my 10,000 hours in the dark room with black-and-white photography and was getting bored; I was ready to try something new. Plus Photoshop was already really great by then, so I could make the photograph I wanted to make.” Thus began his love affair with the color-soaked ethereal imagery that has become his trademark.

Ann Demeulemeester, once an inspiration, soon became a friend and collaborator. Haider Ackermann followed, along with a bevy of other burgeoning fashion designers. “It was the very underground part of fashion that unfortunately doesn’t exist anymore,” he says. “I never really wanted to shoot for fashion magazines per se. I started my own, which wasn’t really a magazine and wasn’t really fashion; I was collaborating with fashion designers to make art for five or six years until just after graduate school. At that point, I started getting commissioned by magazines, and that’s how I got into it.”

It was during his nearly decade-long tenure in New York City — including getting his MFA from Parsons School of Design — that he founded Nomenus Quarterly. Deemed Heck’s self-paved “golden pathway” to success, the definition-defying publication featured work by designers like Demeulemeester, Jean Paul Gaultier and Dries Van Noten as well as artists like Christian Boltanski, Lucian Freud, Kiki Smith and Lawrence Weiner. It wasn’t really a publication at all, but rather a limited-edition box containing prints of oft-unseen artist etchings and photographs. It was at once exclusive — the dozen or so boxes per run cost some $7,500 at its peak — and universal since it was available online for free. Much like the artist himself, it was utterly enigmatic.

So for Heck, where does fashion end and art begin — or are they one and the same? “I don’t think anybody of a critical mind would say that fashion is art,” he posits. “Because fashion is functional firstly, it cannot be art. So even in the most sculptural abstract idea of fashion, like Viktor & Rolf, it is still a wearable item and therefore negates itself as being art. However, I think there is so much craftsmanship and beauty in fashion when you actually look at how things are made and the ideas that go into them. You can make a compelling case that it comes close.”

“Fashion is fashion, and I think it’s fine to just be what it is,” he continues. “I don’t think fashion needs the accolade of being labeled art with a capital A; that’s never what it wanted to be. It’s a symptom of society needing to label everything these days, and people believe that if you call something art, it makes it more grandiose. Fashion is fashion — an object you put on your body. Food is food — nourishment for your body. Art, to me, has no purpose other than to exist for the sake of pure delight. A painting is a painting. A photograph is a photograph. You don’t wear it or eat it. They just exist for what they are.”

Heck has made a name for himself creating art with fashion. The influence behind his ethereal aesthetic goes back to his early art history education. “I grew up looking at mostly French impressionist painting, and most of it was very colorful and romantic showing people in nature,” he notes. “I think when you’re bombarded with that as a child, it seeps into your brain and shapes your worldview for what is good art.”

But the acclaim and adoration he now regularly receives wasn’t instantaneous. “When I went to graduate school, I wanted to make very romantic photographs — but the contemporary art world doesn’t necessarily like that,” he recalls. “There was a lot of ‘Why?’ The answer for me is that there are enough things in the everyday world that give us reasons to be cynical, scared or upset. All you have to do is go on your social media feed and you would think the world is ending in 10 minutes. So when I make artwork, I want it to be beautiful and make people happy, because I feel that’s the responsibility we have as artists now.”

His is a refreshing if not overly popular take. “It’s definitely not an in-vogue perspective on art,” he admits. “I find a lot of contemporary photography to be very cynical, even the work of [Minneapolis artist] Alec Soth, who I adore. But there’s no surface between his lens and the people he’s photographing; it’s just this 1:1 relationship. Whereas I like the sort of dream of a film that takes me to a different place rather than just showing me what’s exactly in front of your eyes.”

Heck’s signature fantastical worlds might give the impression of being created in Photoshop, but they are in fact the real deal. Much of it is captured using that same lens he received as a teen, with little manipulated in post other than amping up the color for visual effect. “If something is shot in studio, we build everything; if it’s shot outside, that’s just nature — I can’t take credit for that,” he notes. “But I don’t invent anything in post-production.” Given that, does he see a future where his work is threatened by AI?

“Anybody who says AI is a threat doesn’t quite understand art history,” Heck affirms. “The exact same thing was said when photography was introduced in the 1800s. Every single painter was like, ‘Oh my God, painting is dead.’ Obviously that didn’t happen. The other thing is that AI is not sentient; it still takes a human to tell it what to do. There’s no difference between giving AI a prompt and pointing your camera somewhere and clicking it. You still have to sample from something. So, if you’re taking a picture of the world, you’re sampling what’s in front of you. If you’re creating an AI image, you’re sampling your own work or something from the Internet. You can always still take a picture; you don’t have to use AI. I think it’s only something to worry about when we cross that threshold of the computer actually thinking for itself. But I’m not a science fiction buff, so I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about that.”

In addition to his fashion photography, Heck has also been tapped to shoot portraiture of notable figures including President Joe Biden, the late great Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, singers Adele and Taylor Swift, and Olympic gymnast Simone Biles, among others. Though a rare honor, the experience is quite a departure from his usual work.

“It’s always very flattering to be asked to shoot portraits, but it’s more of a young man’s game,” he says. “It’s grueling because you’re usually told the night before, you can’t plan for anything and you generally have less than 20 minutes with somebody. If it’s a president, you probably have three to five minutes to make a picture. There’s so much pressure to make something amazing. I actually thrive in those situations, so I was fine with it. But you have to ask yourself why you’re doing it.”

“I think a lot of it comes down to ego so you can tell your friends, or so you have it in your back pocket as a reputation builder,” he continues. “I did most of those editorial portraits in my late twenties when I wasn’t married and didn’t have kids. All I had was my career that I was trying to build and build and build. But now, I would be much more thoughtful about it. Like if I were to photograph a politician, I wouldn’t want to be a tool of propaganda for somebody I didn’t agree with politically. Even with celebrities and musicians, when I ask myself why I would do it now, it would have to be a very compelling reason.”

In addition to the time limitations, Heck also has less creative control given all the players involved, including the subject, the manager, the publicist, the magazine’s editorial team, and on and on. “When you photograph a celebrity or public figure, you’re more constrained in your time and ability to create something personal, whereas in fashion you have much more creative flexibility,” he says. “But both are great for creating; sometimes tight constraints make better work. With fashion, most of the time I’m able to creative direct the whole thing. There are still parameters, like maybe we need to shoot in Scotland. But within that, I can generally do whatever I like — except pick the dresses, of course.”

He tries to shoot every project, whether editorial or commercial, as if it’s personal work. His lauded 2021 book The Garden is the culmination of a six-year daily photography practice shot at his charming Connecticut home, where he and his then-wife relocated in late 2016 to raise their sons. “I tend to get very bored every August because the fashion industry shuts down,” he recalls. “Bri finally said, ‘Why don’t you photograph me and our kids?’ So she forced my hand in a way, but it turned out to be amazing. But I didn’t set out to make it a book.”

The popular coffee table tome features his trademark romantic photography of Bri and their two older sons, Felix and Winston, paired with poetry he wrote surrounding his mother’s 2020 passing from metastatic breast cancer. But, as Heck points out, it’s more fantasy than family album.

“It seems like a dream in hindsight,” he notes. “It was this fairy tale that I was able to make with my ex-wife and kids at the time, which was great, but I don’t view it as a memento. It wasn’t like we were just laying around in trees in dresses; we would set aside time to go make pictures. It was a lot easier when the children were smaller, because it was fun for them and they didn’t really care about the camera. Then they hit a certain age and stopped wanting to be in the pictures, which kind of ruins it.”

The concept also morphed into a way for Heck to make a living during the pandemic, when the fashion world came to a screeching halt. “It was very convenient that we had been photographing Bri and the children because it allowed us to continue working,” he explains. “Companies would send us clothing, Bri would model, and I would photograph. It was an amazing thing to have during the pandemic when nobody was working in my industry.”

Although they moved to Connecticut on a whim based on a recommendation, it suits Heck well. It’s not unlike his own idyllic upbringing in the Twin Cities, which remains one of his favorite destinations. “I think Minneapolis is one of the best cities in the country for its livability,” he shares. “The way it’s structured as a city is very European. You have a lot of likeness to Copenhagen, Denmark, and Stockholm, Sweden, with the lakes. You have quaint little neighborhoods, like Linden Hills, and you have access to a big city downtown if you want. But it’s still very livable. New York City is the antithesis of that; it’s like a concrete terminator that sucks the soul out of you if you don’t leave every weekend. Whereas in Minneapolis, you can have a very relaxed, easy life while still being in a city.”

A decided sense of purpose is driving him these days, a conscious choice he committed to on Instagram, where he’s prone to getting candid. “I think that’s probably just from having three young sons and watching the world change so drastically,” he says. “When you’re a parent and you interact with other families and kids on the playground, it is pretty crazy how you notice an erosion of manners and civility. I experience the same thing in business dealings; the way magazines commission you and the relationships you have are very different now. There seems to be a lack of kindness these days. So I think it is a combination of wanting things to be better for everybody and also turning 40 this year — a natural point in your life when you have to stop and ask yourself, ‘What am I doing?’”

So when it comes to art history, does Heck think he’ll be remembered as a defining figure of this era? “One could hope, but that’s obviously not up to me,” he demurs. “It’s tricky because there’s so much art being made now. I was very lucky to start when I did, because you could still put your stamp on the world. It’s not that it was less competitive, but there were far fewer people making photographs on the world stage because we didn’t have Instagram.”

“And while it’s a good thing that everybody has a voice, I do think it has possibly changed the world for the worse because there’s a lot of noise now,” he continues. “Visual literacy has been diluted because we’re so overexposed to things. It’s a very different world today. But hopefully people still know my work and like it — that’s all I can ask for.” While it remains to be seen how Heck goes down in art history, chances are his enduring ethereal creations will stand the test of time.