Matson Holbrook is 74 years old, but when he’s on the Bois Brule River, he feels like a boy again. It’s the smell that gets him, that unmistakable bouquet of wintergreen and sweet fern, wood smoke and damp earth.

“I just inhale, and it’s like I’m 5 years old again,” says Holbrook, who has been vacationing on the northwest Wisconsin river since the end of World War II. “I tell you, they got the needle in me deep, very deep.” He taps one of the blue veins in the crook of his elbow, as if he were ready to inject some of the river’s trout-tinged water.

Holbrook saw it for the first time in 1945, when his mother pooled her gas rations with a neighbor so she could drive northwest from Milwaukee and introduce her young son to the hallowed waters. He says this river was as much a part of his childhood orthodoxy as God and country.

Later, when Holbrook had children of his own, he cultivated a new crop of Brule enthusiasts. When his kids were babies, he had them photographed with infant-size fly-fishing rods in their chubby hands. When they caught their first trout on the river, he treated the occasion like high-school graduation, proudly snapping rolls of photos. When his clan returned each summer to the Bois Brule, he made them write entries in the family ledger, a bound journal with 135 years’ worth of notations about water temperatures and river conditions.

Holbrook isn’t alone, or even unusual, in his reverence for this place. All along the upper portion of the Brule are the summer homes of well-to-do families that have been faithfully vacationing here for at least four generations. Some of the most moneyed names in the North can be found on this river: Congdon, Drake, Ordway, Rand, Weyerhaeuser. Each family has its own sprawling riverfront estate with spectacular views of rushing water and sky.

It hasn’t all been lemonade in the shade, though. Many of the aged vacation homes are unmerciful money pits, with annual maintenance bills easily reaching several thousands of dollars. The river water is shallower and cloudier than it used to be, and more canoeists and kayakers show up every summer to clog the runs.

Over the decades, the legacy families have been pressured by locals and lawmakers alike to share the scenic wealth. But the upper Bruleites have fiercely clung to the river and resisted anyone who would seek to entreat on their retreat. As the years have turned into decades, then into generations, they have created an unusual upper-crust vacation culture with its own architecture, norms, rituals and language.

A River of Their Own

It started in the 1870s, when the first settlers came to the Bois Brule, mostly from Milwaukee; Duluth; Superior, Wisconsin; and Rockford, Illinois, seeking health or serenity or both. Holbrook knows the story of his progenitor by heart: Milkwaukee dentist Arthur Holbrook was instructed by his physician to seek out some natural pine pollen to alleviate the respiratory ailments that had plagued him since the Civil War.

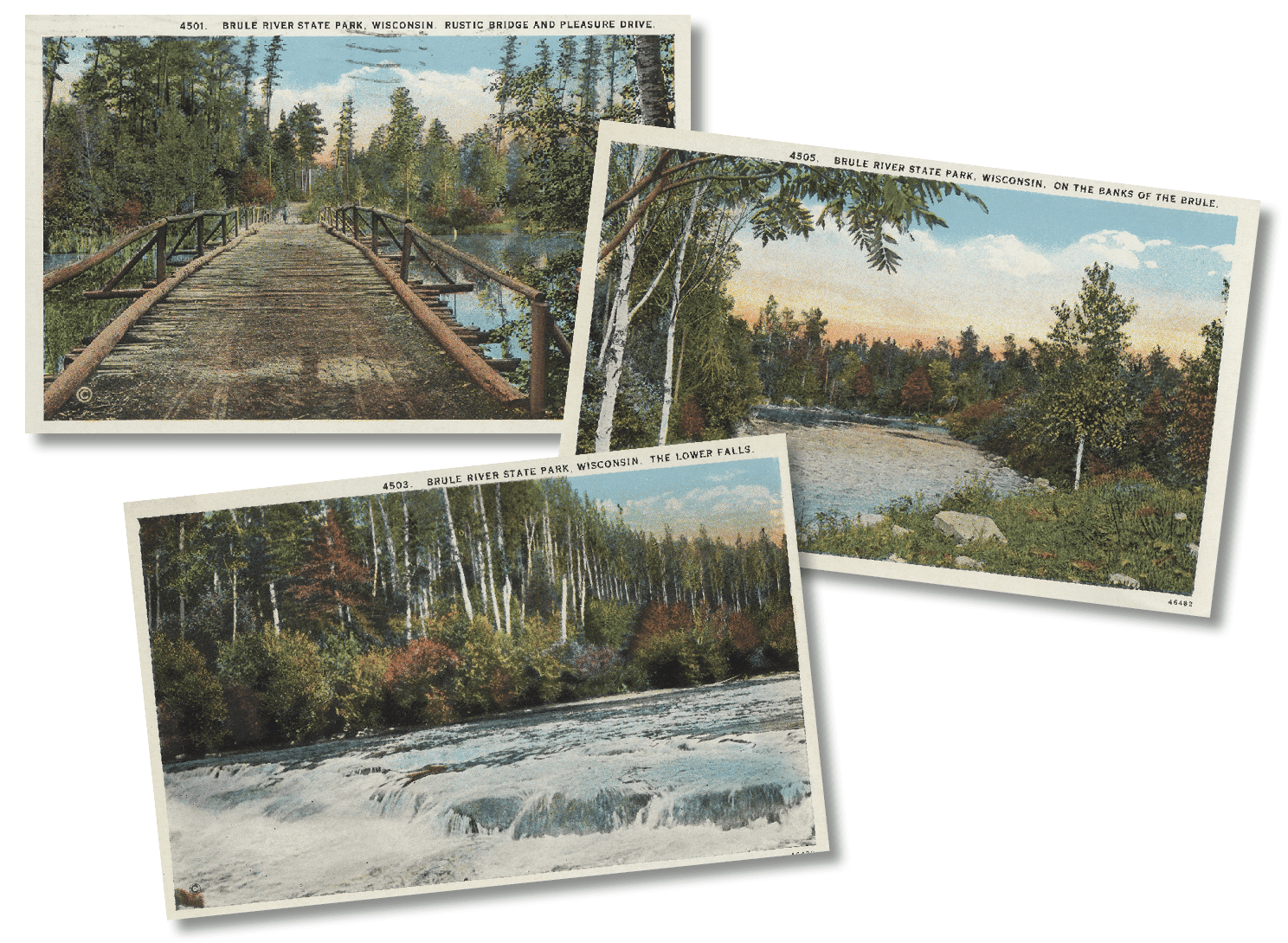

What he and the other settlers found was an unspoiled wild river that flows northward through picturesque Wisconsin valleys and produces millions of gallons of clean, cold spring water from its river bottoms and tributary ponds. The rhythm of the river is fast, then slow, then fast again — lively rapids followed by languid, drifting water through narrow lakes followed by more rapids and more lakes. Local river guides would later call this pattern “puddle and run.” Eventually, the Bois Brule empties into the Lake Superior basin some 25 miles east of the city of Superior.

The settlers, almost all of them financially well-off from banking, medicine, lumber or railroads, set up their primitive camps on the riverbanks among the forget-me-nots and blue flag irises. These camps eventually evolved into sprawling estates with as many as a dozen outbuildings, including icehouses, wood sheds, carriage houses, caretaker cottages, and open-floored bathhouses built directly over the current, for those hardy souls wanting to bathe in cold river water with the Loch Levens, German browns and speckled brook trout.

During the 1890s, loggers sunk their saws into the surrounding valley and trimmed it of 50 million feet of lumber. Consequently, there were few logs for the vacationers’ estates, so most of the multilevel houses on the upper Brule are faux Adirondacks, frame-built and fronted with logs. Almost all have sleeping porches with upholstered mattresses suspended with chains from the high ceilings, lovingly dubbed “Brule beds.” (“As children, we would race to the porches to see who got to sleep on the Brule beds,” recalls Matson.)

The settlers hired local Ojibwa guides to navigate the rapids, pitch their camps and cook them elaborate shore lunches of fresh-caught trout. The wealthy vacationers were so impressed with these “noblemen from nature” that they christened their vacation homes with tribal-like names: Wendigo, Mik-E-Nok, Opechee, Ne Dodgewon. (The Bruleites used Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” as a language guide. Today, linguists agree that he pretty much butchered the Ojibwa language in his epic poem, but que sera.)

The upper Bruleites decorated their riverfront estates with a mishmash of Native American embellishments, including birch-bark lamps and Navajo rugs. A dozen families formed a landowners’ association in 1895, naming it the Winneboujou Club after the Ojibwa deity. A smaller group formed its own association, calling themselves the Gitchi Gummi Club.

The settlers clicked with the Ojibwa-inspired camp theme — there are many romantic references in old letters to “our tribe of Winneboujou” — but they wouldn’t be caught dead wearing deerskin moccasins.

They donned ties and coats on the river and gave each other cryptic, upper-crust nicknames, such as The Judge, The Doctor, The Colonel, The Major, The Baron and The Lawyer. They even published a quarterly magazine, The Brule Chronicles, in the 1890s.

The starched formalities of the early days are now gone, but the new Bruleites have kept the Ojibwa theme, even though the last of the tribal river guides died in the 1940s. Even in 2015, a Bois Brule estate house is still called a “lodge,” not a “cabin.” They hang out in “council rooms,” not “living rooms.” They put their canoes in at “landings,” not “docks.” The oldest families keep photographs of their ancestors with the original Ojibwa guides in the most public room of the lodge, as if to certify that their people were here from the very beginning.

Brule Birthright

It’s no easy thing to keep a culture going for more than a hundred years. Bois Brule families work at it with each successive generation, drilling their offspring on the names of their ancestors. One tradition that survives from the early days? The summertime shore lunches.

“We bring our tablecloths and our big picnic baskets, and it’s a wonderful time,” says Bob Banks, who is descended from two important Brule lineages, Banks and Noyes. A classic shore lunch includes trout cooked “Brule-style.” For this dish, a fish is left whole, rolled in a mixture of flour and cornmeal, and pan-fried in bacon grease over an open flame until light brown outside and moist inside.

Many Brule families spend several thousands of dollars each year to maintain their sagging, century-old estate houses, adding concrete footings to the foundation, leveling floors or replacing logs. The annual maintenance budget at the Wildcat Lodge, for example, is $30,000. But you wouldn’t know it from the inside. Many of the lodges are kept like mausoleums, with tattered, leather-bound books, mice-chewed taxidermy displays and bedrooms with tiny sinks.

“Look here,” says Banks, gesturing to a stack of fishing poles leaning against a corner of Wildcat, next to a dusty shelf of kerosene lanterns. “These fishing poles probably have been sitting just like that for 70 years. And that’s exactly where they’re going to stay.”

It’s the history that is most important, always, on the Brule. “We suggested redoing the bathroom at Noyes Lodge, and Mrs. Noyes just about had a heart attack,” remembers Deborah Holbrook, Matson’s wife. One of the most important artifacts at Wildcat Lodge is a skin mounting of a rainbow trout caught in the river by Banks’ great grandfather, George Noyes.

Fishing, of course, is an important Bois Brule ritual. This is, after all, a premier trout stream that attracts anglers from all over the country. But upper Bruleites tolerate just one kind of fishing: fly-fishing.

“The line between bait fishing and fly-fishing is really cultural,” says Jim Pellman, a historian who has written extensively about the area. “For some people, especially the well-to-do, trout fishing with a fly rod is the only acceptable way. If you use a worm, you’re a slob.”

A Rift Runs Through It

Soon after the settlers had parked themselves on the banks of the Brule, they adopted a code of silence, like a band of tight-lipped morel mushroom hunters. They were afraid people would find out about their forest Eden. In newspaper social columns, the Bruleites would note vague fishing trips to “Lake Superior country” or “northern Wisconsin” or even “the north woods.” Never did they mention the Bois Brule River or the city of Superior.

But people talk. Even turf-zealous morel mushroom hunters. By the end of the 1940s, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland, Herbert Hoover and Dwight D. Eisenhower all had fished the Brule.

No one broke up the secret aura of the place quite as much as President Calvin Coolidge, who decided to make it his “Summer White House” in 1928 and brought with him 60 soldiers, 14 house servants, 10 secret-service men and 75 reporters. He didn’t win any admirers when he fished with worms while wearing his gaudy 10-gallon Stetson hat.

Almost from the start, locals have complained about the legacy families blocking off the river for themselves. In 1906, state legislators took up the issue, and there was an effort at the Wisconsin capitol to have the Brule and its surrounding valley for a mile on either side declared a state forest and fishing preserve.

The newspapers were all behind it. “This would give to the people of the state and country generally one of the most beautiful resorts in the northwest,” mused the Superior Evening Telegram in May 1906. Well-connected upper Bruleites were able to quietly deflate the idea before it went too far.

In 1971, there was a serious effort to have the Brule added to the registry created by the federal Wild & Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. If added, the land around the waterway eventually would pass into federal conservatorship upon the deaths of the current property owners.

The legacy families went into high alert and were able to quash the plan only by putting many of their private properties into conservation easements, perpetual contracts limiting how the land can be developed (or not) in the future.

While batting away attempts at takeover, the upper Bruleites have used the law to mark off their turf as hallowed ground. In 1938, they tried to get a decree issued permitting only fly-fishing on the upper river. After a huge public outcry from regular-Joe bait fishermen, the idea was tabled. They finally did their way in 1998, and now only artificial flies are allowed on the portion of the river where the fancy houses sit. They were successful again in 1981, when a state law banning inner tubes from the river went into effect.

Of late, the legacy families are angry about renovations on Highway 27, which they say destroyed the winding, picturesque drive into the area and possibly caused the silted-up water. “What they did to Highway 27 ripped our hearts out,” says Banks. There’s talk of suing the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. The property owners also are concerned about too much canoe traffic. Personally, Banks says, he would like to see permits for canoers and perhaps even the full prohibition of kayaks.

After all these years, area historian Pellman says there are still heavy class tensions between the upper Bruleites and the people who live year-round near the river. “In some ways, I think it might be a little worse,” he says. “The people on the river used to hire entire staffs of local people to cook and clean for them, and now they don’t do that so much anymore. And the river people don’t often come to town. Or let me put it this way: When they do come in, you hear about it.”

Today, there are more properties for sale on the Bois Brule than at any point in the past. Banks says that’s because the lodges are so big and require so much maintenance. “It’s just too much money for some of the descendants,” he notes. But, he adds, he’s confident that the unusual culture of the river will continue past the 150-year mark: “As long as we keep up the old traditions, I think there will be eight, even nine generations of Brule people. I’m sure of it.”

Chez Ordway

Cedar Island Lodge is the grandest property on the Brule.

Henry Clay Pierce was the son of a prosperous New York doctor, but he aspired to more — much more. He wanted the name Pierce to sing of wealth and power, just as much as Rockefeller and Rothschild.

After he amassed a fortune in oil investments, Pierce had an $850,000, 26-room mansion built in St. Louis, including stained-glass windows personally designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany and a ballroom large enough for 100 partygoers.

When he felt it was time for a status upgrade, he uprooted his five children to buy the Manhattan mansion of multimillionaire banker Richard Thornton Wilson Jr., related by marriage to both the Astors and the Vanderbilts. Pierce bought a yacht from King Carlos I of Portugal and made the papers when one of the monkeys he hired for onboard entertainment bit a guest.

In the 1890s, he heard of a place in Wisconsin where the rich and powerful were beginning to congregate, so naturally, he wanted in. Pierce bought up the largest parcel on the Bois Brule River: 4,100 acres. Over the next 20 years, he constructed 31 buildings on the property, including an eight-bedroom log bungalow with polished, red-cedar walls, and an even larger lodge nearby with a marble-lined kitchen and hand-carved Italian oak library.

Pierce’s compound included all the amenities of a midsize city: a lumber mill, canoe repair, power plant, airstrip, even a small zoo with black bears. He hired famous pisciculturist Fred Mather to design an elaborate fish hatchery and a network of spring-fed ponds for private angling. All told, Pierce spent $1.25 million on his retreat (nearly $17 million in today’s dollars), not including the cost of the forest acreage spanning both sides of the river.

When he died in 1927, Pierce left his heirs without a will, which kick-started a decade of bitter in-fighting. In 1928, eldest son Clay Arthur Pierce invited Calvin Coolidge to spend the summer at the Bois Brule compound. The president brought along his wife, Grace; his collie, Rob Roy; and a fleet of servants, soldiers and reporters.

But it was a short-lived bit of fame for the Pierce family. The estate was declared insolvent in 1938, and the vast Cedar Island Lodge was auctioned off. It was snapped up by Jack Ordway, eldest child of Lucius Pond Ordway, founder of 3M. Though he wasn’t a fan of fish, Jack kept up the ponds and hatcheries, selling prime-grade trout to local restaurants for years.

With Jack’s death in 1966, the place passed to Smokey Ordway, who was known as an excellent fly caster and spent much of his summers fishing the Bois Brule. With Smokey’s death in 2012, the compound passed into the hands of the next generation: John Ordway III, Phil Ordway and Strandy Quesada. Locals say the new owners use the place much less than Jack or Smokey. But the property is perfectly intact, right down to Pierce’s 14-foot mahogany dining table and his maple piano inlaid with gold.