Let’s start with the things Rasmus Munk is not: the world’s best chef is not American. He’s not dressed in an expensive designer T-shirt, and he doesn’t store his jeans in an oven. His blue eyes are not twitching with stress, and he’s not an ego-driven posturer who loves to shout expletives. You probably wouldn’t recognize him and likely have never heard of him, but at 33, Danish chef Rasmus Munk has achieved more than most chefs will in a lifetime.

Dressed in a plain black T-shirt and trousers with dark inkings of ferns and leafy plants on his arms, he’s seated across a low table from me in his Copenhagen restaurant, Alchemist, digesting what it means to be voted the World’s Best Chef at the 2024 Best Chef Awards. He speaks with a Danish accent, at times so quietly that I need to push my recorder across the table to catch what he’s saying.

“It means a lot to receive it, and I feel very privileged,” he says, taking a pause. “Of course the title is amazing, but I don’t believe in such a thing, that there’s a best chef in the world, because how do you compare them? But I do think we’re one of the most interesting restaurants in the world right now.”

The accolade recognizes his avant-garde approach and visionary contributions which have, the awards team says, redefined modern gastronomy. The immersive theatrical experience he has created at Alchemist has earned him global acclaim, two Michelin stars within seven months of opening and a coveted spot in the top 10 of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

The first person he called when he got the news was his mum, a retired care worker in Jutland, rural Denmark, where he grew up.

“She was like, ‘so, there’s nothing more to achieve now,’” he says, laughing. “‘You achieved everything, right?’”

He’s laughing because the idea of packing up now, at the peak of his game, is ridiculous. There’s just so much more at stake.

“Every time they award the best restaurant in Denmark or Europe or the 50 best in the world, you want to do as well as possible on those lists because a prize like this opens doors,” he says. “I’m very aware of using this spotlight to create something for the greater good.”

If Munk was simply a world-renowned chef serving billionaires dinner four times a week in his extraordinarily expensive restaurant — the fixed 50-course, six-hour dinner costs around $765 per person before drinks — it would still be impressive. But his ambitions go way beyond just feeding the 1%: For him, it’s about changing how we look at food. Along with Alchemist, Munk runs Spora, an innovative food lab working on global food challenges, as well as JunkFood, a charity that provides food for the homeless in Denmark and other multidisciplinary projects, including the development of better hospital food.

Alchemist is a portal for this altruistic work. His signature Space Bread came out of work he conducted with MIT’s Media Lab designing food for space travel. Using a new technique, they created a ball of soy with the texture and crunch of bread that disappears on the tongue. In space, crumbs are banned due to the hazards they can create in machines and tubes. The research has been useful in many ways, not least in devising options for long-term sick children in hospitals who want to eat something crunchy but can’t because of their health conditions.

Social justice has interested Munk since the start. His culinary school teacher, Martin Knudsen, said that when he was younger, the chef had expressed interest in being a lawyer “because there was so much injustice in the world.”

“He won all the competitions as a young chef,” said Knudsen. “But it was always more important to him that he was changing food and using it to tell stories. The purpose of his brilliant restaurant is making the world a better place. He’s a man with a big heart.”

In his restaurant, the former theater set-building workshop of the Royal Danish Theater, this story plays out four nights a week.

The 13-foot-high bronze doors open silently. My dinner companion and I start in a small room where a large cubed TV is broadcasting scenes from history. Man lands on the moon. The Berlin Wall falls. The Spice Girls are singing; Geri Halliwell wears a Union Jack dress. It takes me a moment to realize that Geri has my face. In fact, all the characters are me and my companion: In this retelling of mankind’s history, we’re cast as the main characters, our faces shining out from the TV. As the doors open into the next room, a cozy lounge bar, I’m already dazzled and disconcerted, which is, of course, the point.

We watch through a window as teams of chefs create the perfect omelet in front of our eyes, make pisco sour cocktails that sit like an egg yolk in the middle of a silver flower and meticulously plate freeze-dried nettle butterflies on a silver branch. We eat multiple delicious mouthfuls, bug-eyed with amazement.

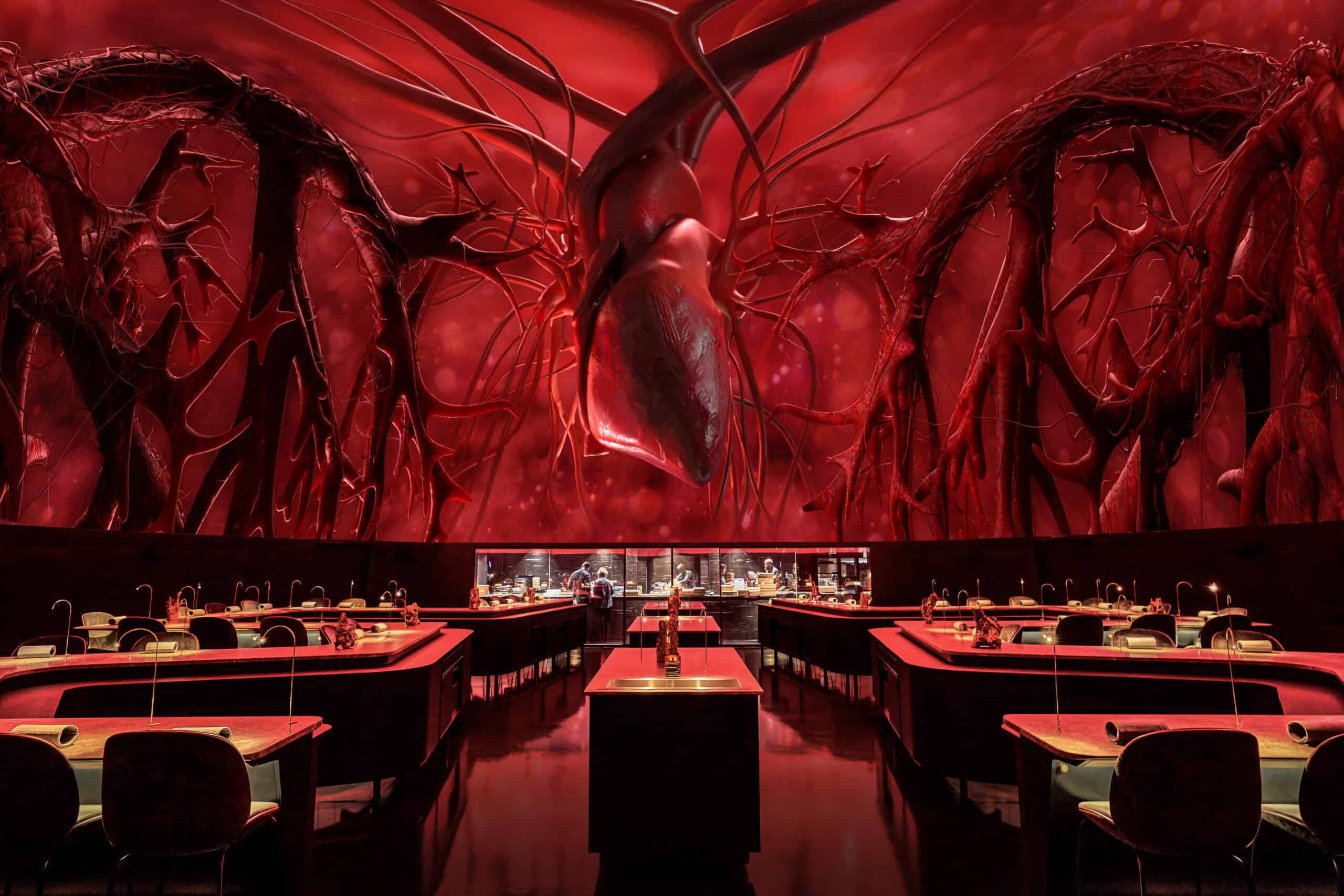

In the main dining room, projections play above our heads of turtles swimming in a Pacific-blue sea, caught up in plastic garbage. The domed ceiling evokes a planetarium or immersive artwork and brings a sense of drama. Lava fills the screen, and then we’re inside a giant body, watching a beating heart as the first course arrives at our table.

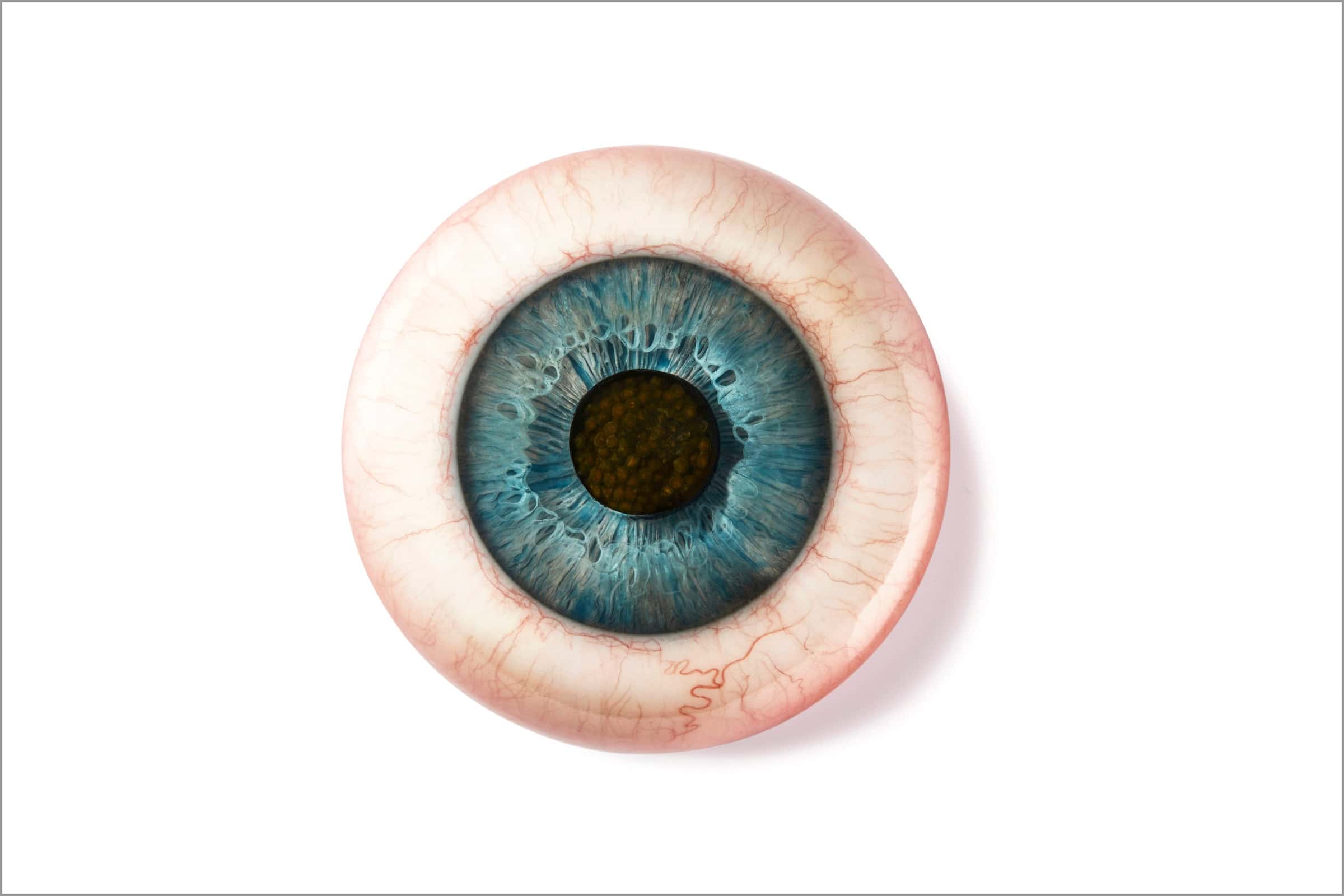

We begin with a dish called Autumn Kiss. Served in an anatomically accurate model of a human tongue, this beef tartare appetizer is meant to highlight how cutlery can change the experience of a meal. Next up there is Hunger, a thin layer of rabbit decorated with wild flowers draped over a silver skeleton meant to evoke the plight of undernourished children. As we swallow our guilt along with the rabbit, we are presented with Plastic Fantastic, a mini ocean garbage patch of edible plastic floating on a square of blue resin that tastes like the most divine bite of fish and chips I have ever tasted. Then there’s 1984, a delectable medley of steamed lobster claw, yuzu juice, roasted cherry tomatoes and caviar that’s served in an enormous resin model of Munk’s eye. As we tuck into what tastes like heaven and looks uncannily like the chef’s own pupil, dystopian images of screens and a huge eye watch on above us in the ceiling projection to remind us of the surveillance state we live in. The experience is to other restaurants as a James Turrell art installation is like a Turner landscape.

Twenty courses in, my dining partner and I are feeling overwhelmed. Munk told me that during nearly every service, one or more guests will cry. I feel like I could be one of them. It’s not that the experience makes me sad; it’s the pure sensory overload of it all. I cut into a tiny, perfect heart, and blood pools on the white porcelain plate. This one has eight flavors, one for each of the people you could save if you participate in organ donation.

It’s not all this heavy: Among the more jarring dishes, a tiny lightbox shows up with a cream of white beans in the shape of my face. I’ve never eaten my own face before. I can’t stop laughing. We eat a scrumptious crab toast made from local Danish crab and a divine lobster claw inspired by a Connecticut lobster roll. Before leaving the main dome to repair to the final lounge for petit fours and coffee, we take a detour into an art room where we dab edible paint all over the walls. I draw a series of big smiley faces.

Munk has been popping up all night and is there to see us in the final coffee lounge again. He is present at every dinner in the restaurant, serving impressions, supervising the kitchens and talking to guests.

While the food here has broken frontiers in my mind — I’m still marveling that I ate my own face — Munk has his eye on another frontier: space. In late 2025, Munk will be cooking food at the edge of the earth’s atmosphere for the space travel firm Space VIP. With the team, he is currently brainstorming how to create his unique brand of boundary-pushing gastronomy in a tiny area with a kitchen the size of two airline trolleys. Oh, and without a naked flame.

“In many ways, it’s a strange idea for me because I’m a control freak and I’m afraid of heights,” he says. But like the title ‘best chef,’ it’s a way to open doors so people want to collaborate with us.”

“In those collaborations, a lot of magic happens. We try to connect all of those different perspectives, and the outcome sometimes becomes an innovation.”

That’s the Munk process right there: Shoot for the moon, and you might land among the stars. Or if you’re him, you’ll achieve the impossible and land on them all.