Deep within the heart of the Ozarks settled under Springfield, Missouri, is an old urban legend: caves filled with cheese. As the story goes, back in the eighties, the subterranean spot housed enough surplus cheese — some 1.4 billion pounds — to wrap around the U.S. Capitol. That heyday fizzled out in the nineties, when the federal government got rid of it. But like any good folklore, the mystique lives on.

The mere existence of cheese caves sounds like the plot of a, well, cheesy sci-fi flick. One that begs a lot of questions: How did this all start? Where did the cheese come from? Where did it go? And what’s stored in those caves now?

Let’s start at the beginning, in the seventies, when the United States experienced an unprecedented dairy shortage. The decade’s energy crisis tanked the economy, sending dairy prices soaring. To address the issue, President Jimmy Carter set a new subsidy policy in 1977 that dumped $2 billion into the dairy industry over a four-year period. But by the eighties, America had gone from too little milk to too much of it.

The solution? Turn lemons into lemonade. Or, in the government’s case, turn milk into cheese. The U.S. Department of Agriculture purchased the surplus milk, processed it into blocks of cheese, and tucked it away hundreds of feet below Springfield in 3.2 million square feet of former limestone mines. An elaborate cooling system regulated the warehouse’s temperature (around 36°F) and relative humidity to help preserve the goods.

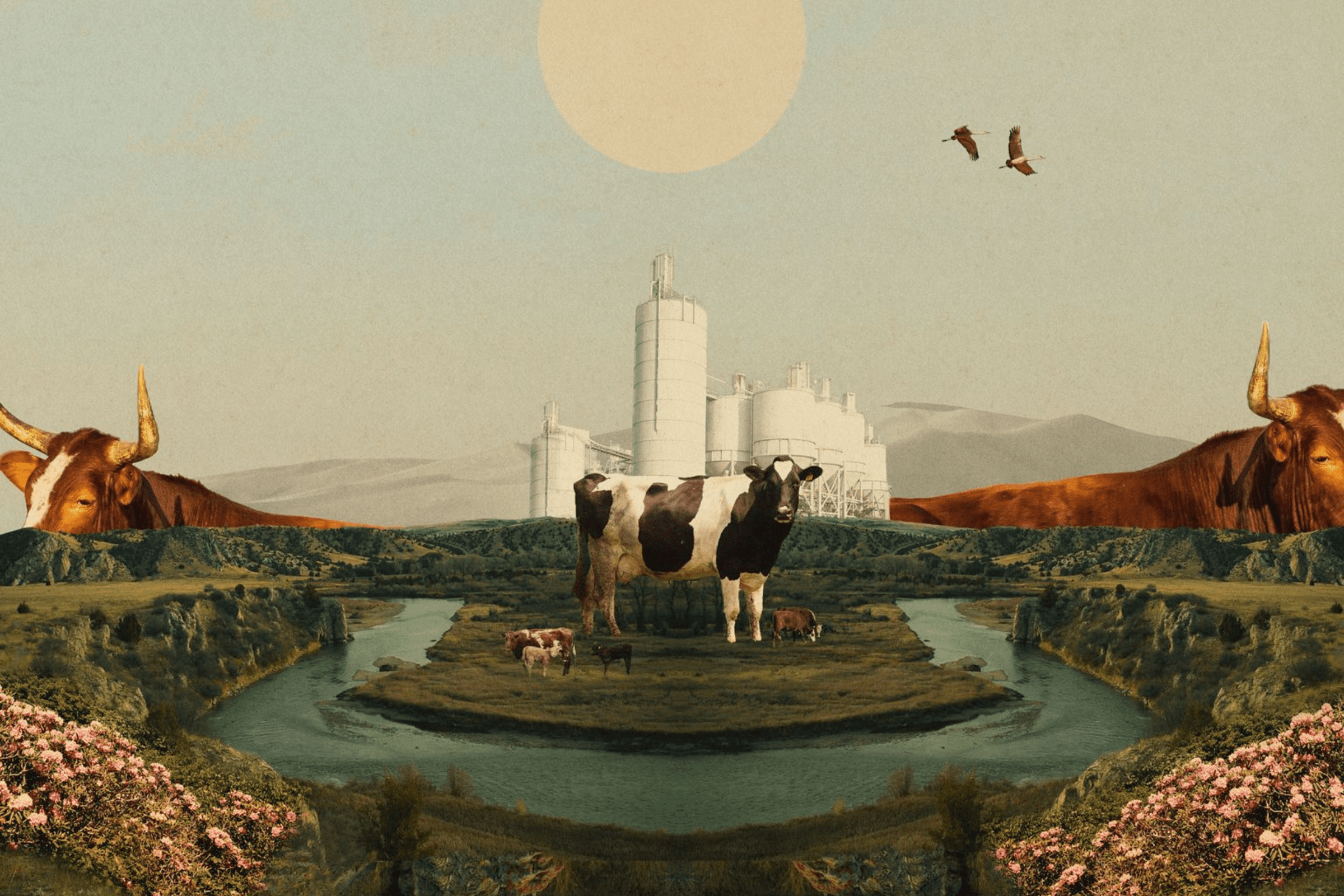

Illustration by Frank Moth

“The U.S. government owned so many stocks of cheeses, butter and nonfat dry milk, they were running out of places to put it,” explains Cornell Agricultural Economics Professor Andrew Novaković. “So, they used this underground storage facility — think Indiana Jones and the final home of the Ark of the Covenant.” By 1981, the government had a treasure trove of aging cheese — and no idea what to do with it. A USDA official even told the Washington Post that “probably the cheapest and most practical thing would be to dump it in the ocean.”

But President Ronald Reagan had a better idea. Spurred on by public criticism, in December 1981 he announced his plan to give it away. He debuted the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program, which ultimately distributed some 30 million pounds of cheese to elderly and low-income individuals.

For some people, the handouts brought joy. “The kid generation had these really fond memories of the cheese,” says University of Louisville Associate Professor Kristen Lucas, who interviewed families of this generation to understand how they remembered the 1980s recession; every single person brought up the cheese. “One woman remembered how her brother kept the cheese boxes because he stored his baseball cards in them. Even years later, they had these moments of nostalgia.”

Reagan’s program was alive and well in places like Ishpeming and Negaunee in Michigan. During the recession, countless men in these remote mining towns were out of work due to the suffering auto industry. “For them, the cheese tasted like shame,” Lucas adds. “They couldn’t provide for their families. For them, there were no happy memories about it.” A clear theme surfaced: The cheese was more than just cheese, representing both hardship and resilience.

But even Reagan’s TEFAP program didn’t deplete the stockpile. So in the nineties, the National Dairy Promotion and Research Board created Dairy Management Inc. to empty the caves once and for all. Its prerogative? Squeeze as much milk, cheese and yogurt into big-name brands as possible. Bloomberg went as far as calling DMI the “Illuminati of cheese,” describing it as “a secretive, government-sponsored entity putting cheese anywhere it can stuff it.”

And stuff it they did. This cheesy Illuminati is to thank for food phenomena like Domino’s seven-cheese and stuffed-crust pizzas, Taco Bell’s Quesalupa, Yoplait yogurt chips, and even the celebrity-studded “Got Milk” ad campaign. DMI’s hard work paid off, and soon enough the cheese caves were effectively emptied. In fact by 2000, Americans were eating 32 pounds of cheese each — four times what we consumed in 1970.

“An ill-fated attempt to prop up the farm price of milk got out of hand in the 1980s, but that problem went away in the 1990s,” explains Novaković. “The government ratcheted down its price support policy until the program became all but meaningless. These days, programs enable the government to buy food for donation purposes, including dairy products.” Essentially, the USDA decides what food will be sent to hunger-relief organizations like Feeding America, then it gets delivered to their warehouses for distribution — no caves necessary.

And yet the rumors persist. “Folks are still trying to sensationalize these numbers by suggesting that the cheese stockpile is still bigger than the Capitol building,” says Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Now, the caves are primarily used for cold storage for all kinds of products, not just dairy.”

So are the cheese glory days behind us? It depends how you look at it. Today, Americans consume more cheese than ever, with each of us eating about 40 pounds per year. For the families who experienced the government cheese handouts of the eighties, like the miners of Michigan, those memories are visceral. The legendary Missouri caves still hum just above freezing, but not for a mountain of cheese (more like a molehill). Despite that, the mystique remains. After all, who doesn’t love a good tale about hidden treasure?