In 1960s post–Cold War America, a high-tech, sci-fi future seemed right around the corner. A life filled with Jetsons-style robots, touchscreens and flying cars felt not only possible, but inevitable. At the same time, urban areas across the country had started buckling under the rapid growth of the population.

Rather than flee to the suburbs alongside his white, middle-class peers, Minnesotan scientist and eccentric Athelstan Spilhaus had a bold idea: What if all this new technology could solve modern urban dilemmas like crime, pollution and overcrowding? And what if, instead of trying to incorporate these developments into existing cities, we built an entirely new one — one away from any existing mess, outfitted with the most ambitious advancements and enclosed under a geodesic dome to protect it from the elements?

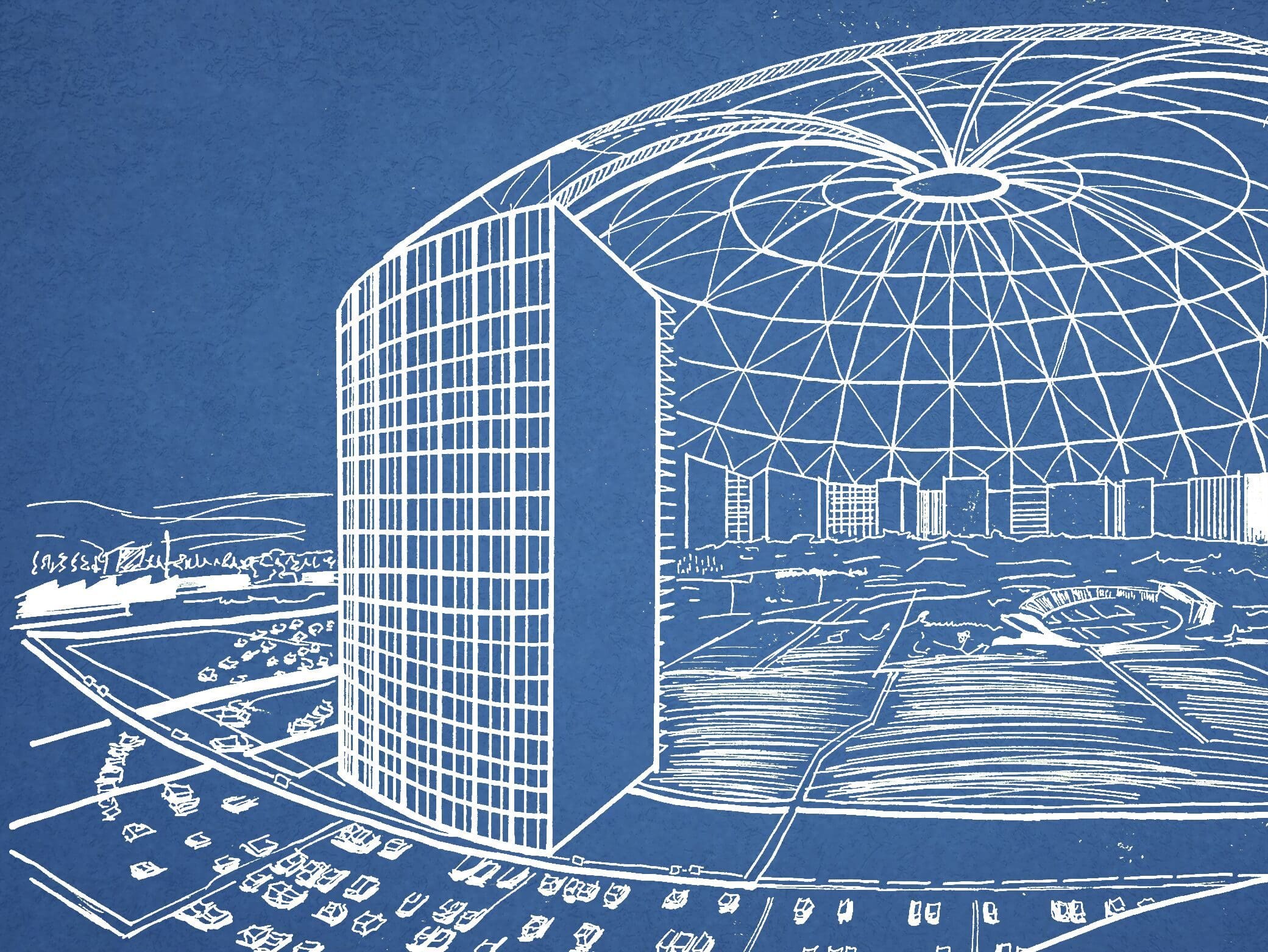

Illustration by Braden Cooper

The idea progressed to the point where a site was chosen: the unincorporated 204-citizen community of Swatara — about as close to nowhere as you can get. Spilhaus and his fellow scientists saw the sprawling farmlands as fertile ground in which to plant their wildest dreams. Some 250,000 people were projected to move to this new city, along with major companies like 3M and Honeywell. Plus the project had buy-in from Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, the state government and a high-profile advisory board of scholarly masterminds like Buckminster Fuller.

There was only one problem: No one told the people of Swatara about the big plans. And once the residents found out, their resistance played a big part in bringing the $4-billion project to a screeching halt.

The story of the North’s failed futuristic city, officially dubbed the Minnesota Experimental City, is so bizarre it’s a wonder that more of the state’s residents don’t talk about it. But of the project’s many missteps, its largest was its failure to reach outside the bubble of elite scientists and social engineers who cooked up the idea and communicate with the public. And so MXC lived and died mostly in secret, with millions of state dollars quietly funneled into a project that amounted to little more than a dozen file boxes of sketches, meeting notes and lost dreams.

Dean of the University of Minnesota Institute of Technology, Spilhaus was a restless, radical intellect. This inventor, geophysicist, meteorologist and oceanographer channeled many of his ideas for the future into the nationally syndicated comic strip Our New Age.

Some of his fascinations proved prescient. His first-ever comic, published in 1958, warned that an increase in carbon dioxide caused by burning fossil fuels could trap heat in the earth’s atmosphere, declaring “We live in a greenhouse!” Other strips envisioned a future filled with self-driving electric cars — an idea that has only recently been embraced by the mainstream thanks to entrepreneur Elon Musk — and personal computers that could connect users to a global network of information.

Photography provided by Chad Freidrichs/Minnesota Experimental City

Spilhaus created the comic strip with the intent of teaching scientific ideas to hungry young minds who were more apt to read the funnies than a textbook. But by the early sixties, the influence of Our New Age on the leading minds of his generation had been firmly established. When he met John F. Kennedy in 1962, the president told him, “The only science I ever learned was from your comic strip in the Boston Globe.” In fact, Spilhaus had already contributed one seemingly far-out invention to the world: a system of covered, second-floor skyways to protect city dwellers from extreme weather, today found across Minneapolis and St. Paul.

So when he began floating the idea of an experimental city in Our New Age, politicians and engineers were intrigued. What might sound like a far-fetched fever dream became a clarion call. Cities were expanding too rapidly to remain healthy, Spilhaus argued, and an experimental city could create a testing ground for new systems of modular building, mass transportation and waste management. A dome would protect residents from the elements and help mitigate the effects of climate change.

“It is not only to be a viable city in itself,” he told Minnesota Public Radio in 1972, “but to be a laboratory for the testing of both technological and social innovations that once proven can be introduced into the older cities.”

As his idea snowballed, Spilhaus launched an informal speaking tour to sell the concept to other leaders in the scientific community. He had the early support of Otto Silha, president and publisher of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune, and together they secured enough funding to officially launch the project in 1966.

Between the two of them, the duo had enough political and social capital to assemble a national advisory committee and begin bending the ears of Minnesota decision makers. They spent the next several years in smoke-filled conference rooms drafting up plans and debating the technical details: Would MXC be a utopia or an ever-fluctuating system of trials and errors? What if the buildings could be disassembled and moved around like modular furniture? And would it have a dome or what?

Oddly enough, discussion of the location for such a major project came late in the game, and it wasn’t until 1972 that the committee began making site visits and narrowing in on economically depressed Aitkin County. By this point, Spilhaus had long departed from the project, frustrated by the bureaucracy and bored by the slow pace of development. The committee had evolved into the state-backed Minnesota Experimental City Authority, with members appointed by Governor Wendell Anderson. It was given a budget ($140,000) and tasked with proposing a site to the state legislature by the spring of 1973. And so the process of whittling down potential locales finally began.

Illustration by Braden Cooper

The authority knew it wanted the experimental city to be at least 100 miles away from a major metro area and surrounded by lots of open green space to stave off the overcrowding that plagued other cities. Swatara fit the bill, with an added bonus: Not only was the town enveloped by large swaths of undeveloped land, a state park and a national forest, but the population was dwindling and struggling to stay employed. Surely they would welcome the chance for something as exciting as MXC.

“Because of the economic situation in Aitkin County, the thought was that residents would be receptive to development, whether or not that happened to be under a domed city,” says Chad Freidrichs, director of the 2017 documentary The Experimental City. “The thinking was that they would be welcoming to people who were bringing economic development to a place that was in dire straits at the time.”

Turns out that thinking was wrong. “Some things you just can’t predict,” he continues. “How can you predict that the people of Swatara weren’t going to want a futuristic city dropped on top of them?”

Visit Swatara today, and you might think you’ve stumbled onto a vacant film set. A weathered general store is frozen in time along the block-long main drag, one ancient gas pump left unattended on the front sidewalk and paint peeling away to reveal rotting wood underneath. Down the street, another building is so dilapidated it looks like a strong gust of wind might blow it over like a house of cards.

The only remaining sign of Swatara’s early 20th century prosperity is an old railroad platform that’s been turned into a roadside sign greeting passersby. The only visitors passing through are the ATV riders and snowmobilers who roar from town to town along the Soo Line Recreation Trail, occasionally stopping off for a beer or a sandwich at a local watering hole. Even that is a rare enough occurrence that a stop at the Corner Club is met with raised eyebrows from the lone bartender and patron who sit inside.

Photography provided by and used with permission from the Minnesota Historical Society

These days, few locals have any desire to discuss the crazy plan for the domed city that almost displaced Swatara. But back in the winter of 1972–1973, it was the talk of the town. As soon as the newspapers reported that Aitkin County had been chosen as one of two possible sites for MXC (the other being a small town in Douglas County), residents began writing panicked letters to the governor, all of which remain neatly stacked in manila folders at the Minnesota Historical Society like a time capsule.

Some saw the experimental city as a chance for a brighter future: “We need jobs badly,” wrote Gladys Garner. “Our forests have been cut down many times. Our fish are few — far apart and small. Our hunting is gone. … We’ve lived here since 1934. My husband and three boys have all had to go away to earn our living.”

Others saw it as a devastating blow to an already hurting town: “My father-in-law and I stand to lose our homes, our land and our small place of business,” wrote Roger Sundberg. “That doesn’t give a man much to live for, does it?”

Ben and Carol O’Brien, meanwhile, wrote countless impassioned letters tagged with the phrase “Save Our Northland” and peppered with dramatic pleas: “Give us liberty or you will give us death (our hopes, dreams and homes).” Unsatisfied with the lack of response, they took matters into their own hands and staged a protest. To show just how upset they were, the O’Briens walked the 170 miles from Swatara to the state capitol in subzero temperatures to hand deliver a signed petition to Governor Anderson.

The Minnesota Experimental City Authority officially chose Swatara as the proposed site on February 12, 1973, but the entire project died soon thereafter due to public backlash, the changing political climate and pushback from the Pollution Control Agency. The legislature, which had turned from Republican to Democratic control in the beginning of the year, completely backed off MXC, writing it out of the following year’s budget. In a scramble to dissect the now very public dilemma, newspapers didn’t know whether to blame the people of Swatara, the committee, the government or all of the above.

Swatara residents did their best to return to their quiet country lives, though many still carry grudges about the doomed domed city to this day. As George Trepanier told the Star Tribune in a follow-up story in 1987, ‘‘You can’t stop progress. But they did.’’