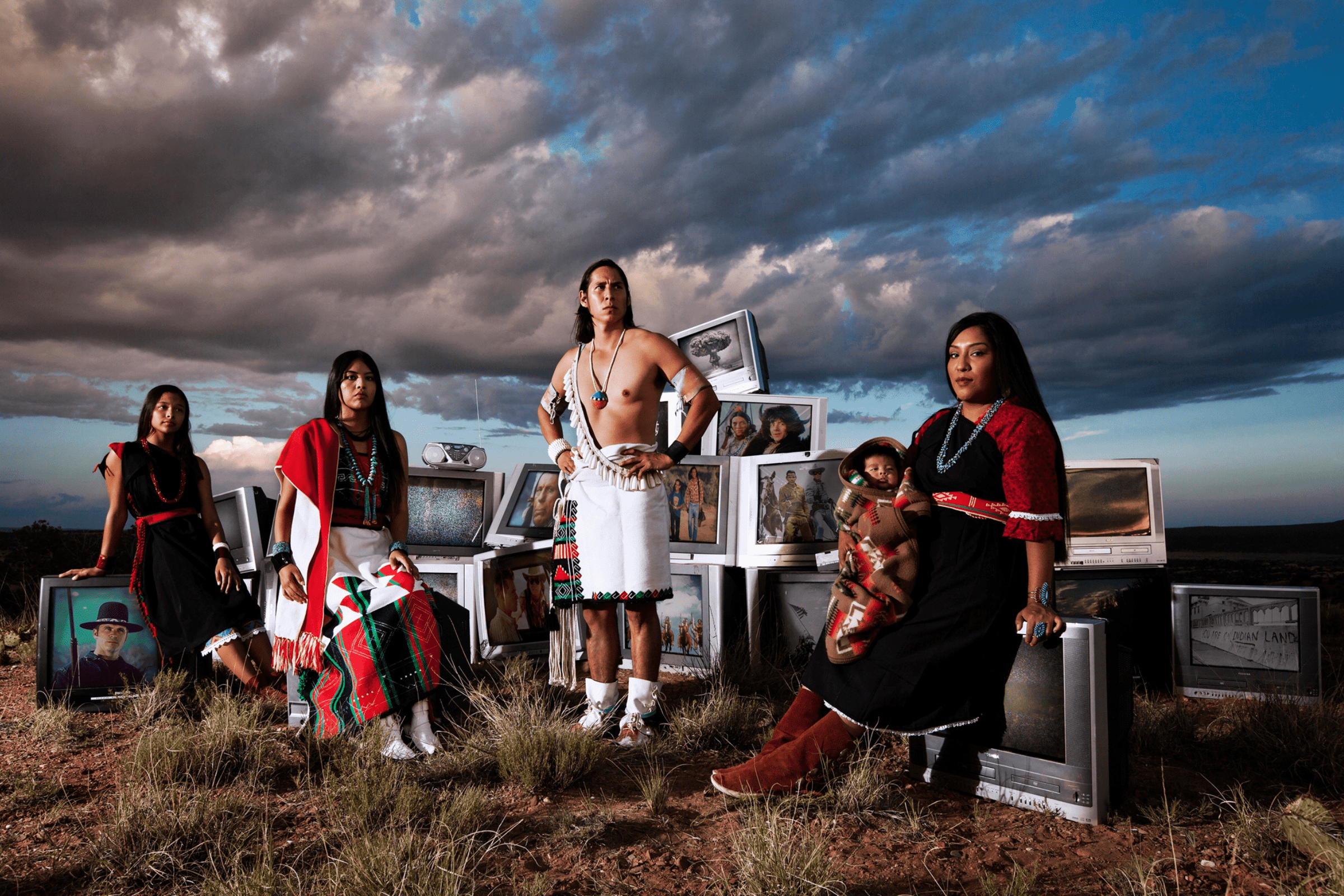

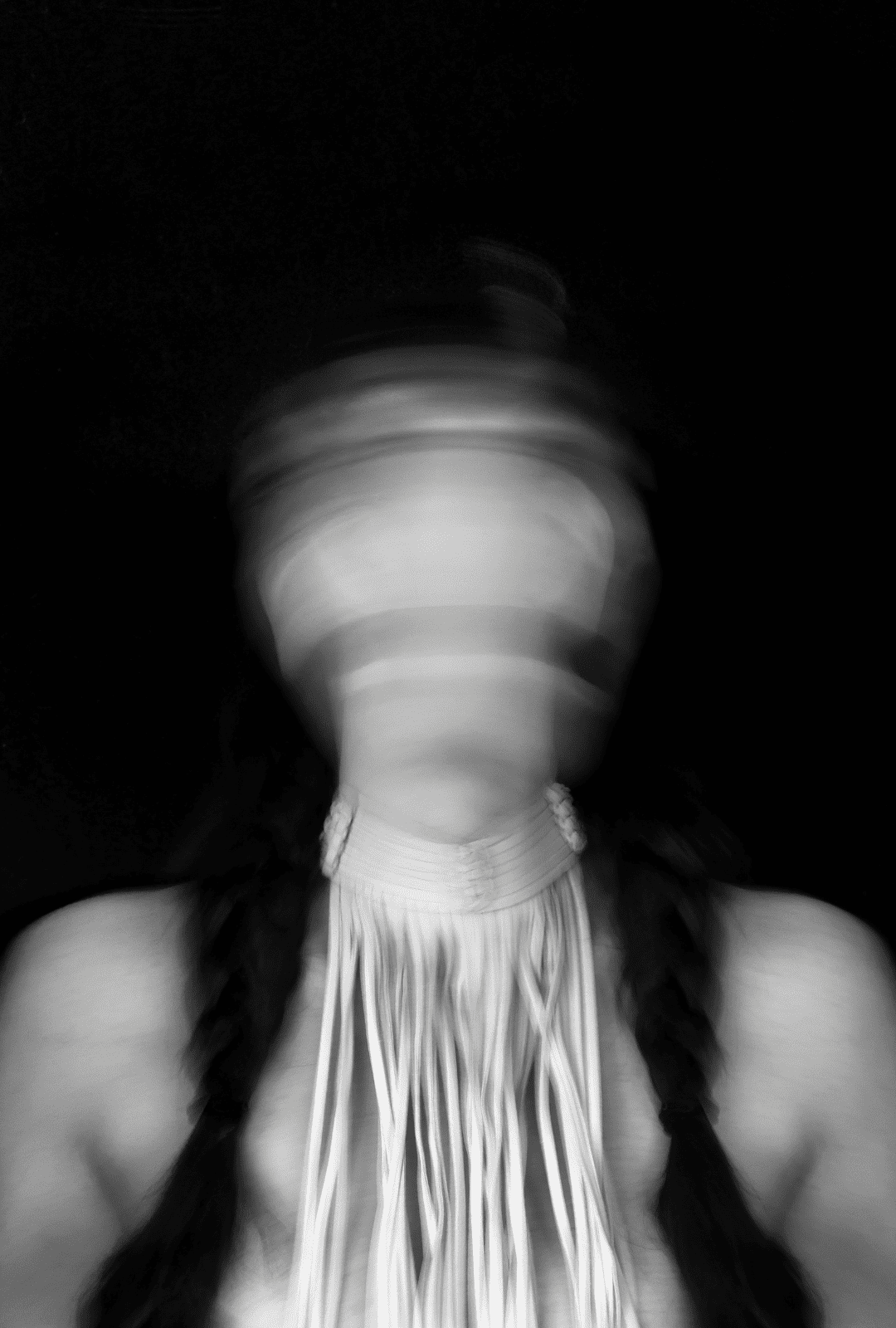

A new Minneapolis Institute of Art exhibition is helping break barriers and shatter assumptions about Indigenous art. On view through January 14, 2024, In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now features more than 150 works by renowned First Nations, Métis, Inuit and Native American creators exploring complex topics such as Indigeneity, environmentalism, human rights and more.

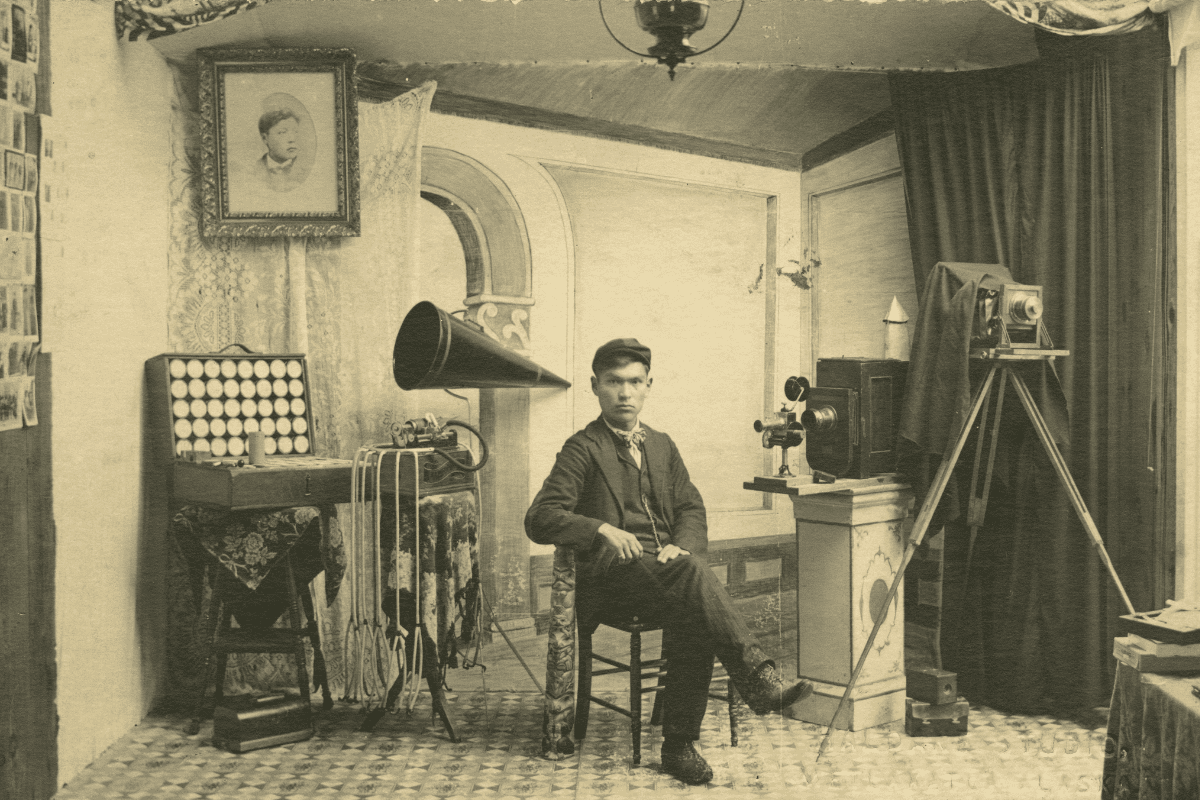

The exhibition highlights celebrated photographers from the past — including Lee Marmon (Laguna Pueblo), Peter Pitseolak (Inuit), Louis Situwuka Shotridge (Tlingit) and Richard Throssel (Cree/Adopted Crow) — and the present — including Kalen Goodluck (Diné/Mandan/Hidatsa/Tsimshian), Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo), Ryan Red Corn (Osage), Sarah Sense (Chitimacha/Choctaw), Matika Wilbur (Swinomish/Tulalip) and many others. To curate this groundbreaking exhibition, Mia engaged a curatorial council of artists, academics and knowledge sharers and also tapped Twin Cities documentary photographer Jaida Grey Eagle (Oglala Lakota) as a guest curator. Here, she discusses why amplifying Native artists is so important and what she hopes museum goers take away from this exhibition.

“Benjamin A. Haldane Self-Portrait in Studio in Metlakatla” | Artwork by Benjamin A. Haldane, provided by Ketchikan Museums

What was the inspiration behind In Our Hands?

When I first came on as a curatorial fellow under the Shakopee Mdewakanton program at Mia, I was interested in Mia’s collection of Native art, particularly photography. Mia was just finishing its incredibly successful run of Hearts of Our People, and I was interested in what was next. Jill Ahlberg Yohe introduced me to Casey Riley so that we could discuss Native photography, and we came to find that there was this incredibly vivid world of Native artists creating work within the canon of photographic practices. We proposed a show uplifting that work, and museum leadership supported it. My role eventually evolved from fellow to co-curator, and I’ve stayed on for a number of years helping bring this exhibition to life while learning from Jill and Casey.

Why was it important to engage a Native curatorial council to bring this exhibition together?

So much of Native history has been erased from the contemporary timeline. It’s important when working on projects to bring forward many different generations of knowledge but also to celebrate the diversity within the Native community. I’m thankful for the curatorial council because it honors and shapes the vast depths of knowledge, timelines and diversity of Native nations. Coming off the success of Hearts of Our People, I believe curator Jill Ahlberg Yohe and artist/guest curator Teri Greeves helped set the path for shows like this to come together through a democratic and thoughtful process that honors Native peoples’ contributions to the field of art, as so often we have been left out of the conversation by institutions.

Can you talk through what museum goers will experience in the three thematic sections?

Upon first walking into the exhibition, you will experience “A World of Relations,” which honors Native peoples’ relationship with all living beings. We understand the living world holistically, choosing to act with deep respect for all forms of life and their interconnectedness. Land, water, the cosmos and all living beings are relatives to be treated as family.

You are then led to “Always Leaders,” which recognizes Native peoples’ leadership within environmental and social movements while also honoring that, since the 19th century, Native photographers have embraced the camera to manifest these values and create a more just and inclusive world.

And finally, the “Always Present” section recognizes that Native people are active in every facet of North American life. I hope that it also serves as a reminder that not only are we still here, but we’ve been here and will remain here. I hope people are impressed upon to use active language when speaking about us and to stop thinking of Native people as in the past.

As a local Indigenous photographer, what does it mean to you to have this groundbreaking exhibition on display in Minneapolis?

I don’t know where else this show would have debuted, to be honest. I think Minneapolis has shown itself to be a leader in so many facets, especially within the Native community. I think it not only makes sense, but it’s deeply meaningful for the place and time.

What do you hope audiences take away from In Our Hands?

I hope people take away a deeper understanding of Native people and embrace our diversity, our contributions and our worldviews. I hope that in the future, shows like this are not needed because we will have set the standard of embracing all viewpoints and voices when speaking about our collective histories and stories.