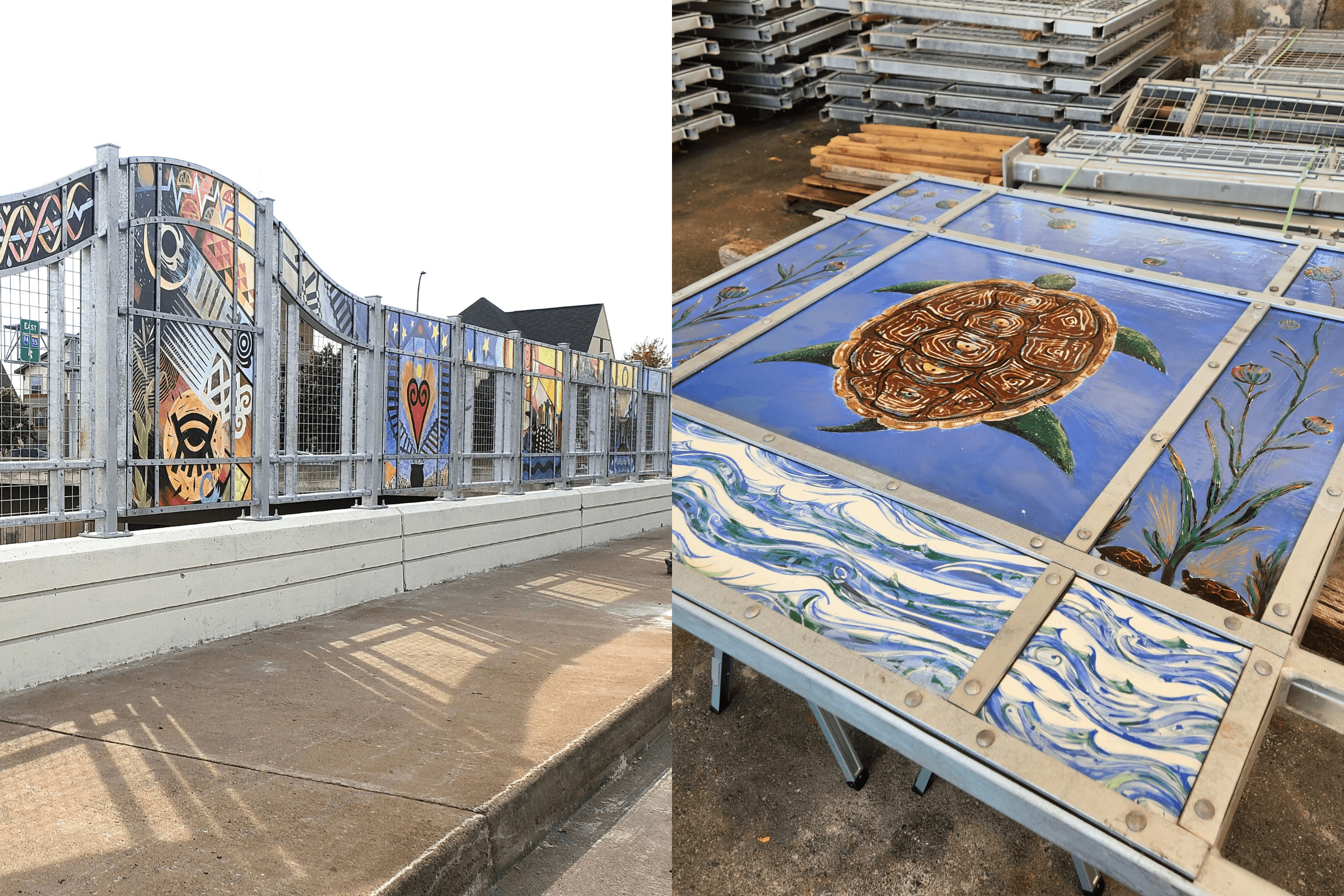

There’s a breathtaking distraction from the billboards and LED displays lining the expressway as you drive north through Minneapolis on I-94: a porcelain bridge emblazoned with African mud cloth symbols and patterns — including hundreds of Adinkra spirals, sun rays and shields. It’s worth taking Exit 230 just to see where the Olson Bridge suddenly bursts with color, welcoming pedestrians who cross it with enormous six-foot enameled panels glazed with bright orange and yellow swirls, turtles swimming in azure blue rivers, and dancing green stars.

There are many stories being told on this bridge — stories about art and politics, a community’s history, and a people’s legacy. “Nothing beats a failure but a try,” says Ta-coumba Aiken. The Guggenheim Fellow was one of the leaders of a dozen community artists who lobbied nearly a decade for the project, then taught themselves how to create it. “Nothing in the United States will outshine this bridge. It’s the gem of the Northside.”

In 1996, nationally recognized artist John Biggers painted his “Celebration of Life” mural on a sound wall of Olson Memorial Highway in one of the city’s predominantly Black areas. The locality had once thrived with businesses, homes and shops, only to be crippled when Highway 55 — one of the first urban freeways — was built through the heart of the neighborhood in the 1930s. Known for creating works influenced by African myths and symbols, Biggers painted the 160-foot mural to be seen from I-94 like a way-finding sign for Near North, better known as North Minneapolis.

It wasn’t long afterward that the city of Minneapolis decided to build Heritage Park, an affordable housing project along Olson Memorial Highway, right where Biggers’ mural stood. It was demolished in 2000, and two years later, the iconic artist passed away.

The pain and anger of the community ran deep. “The mural’s destruction underscored the need to preserve and celebrate such cultural landmarks,” says artist and Juxtaposition Arts’ Chief Cultural Producer Roger Cummings, who was one of the apprentices on the project. “It made Biggers’ legacy an essential reminder of the significance of art in a community’s identity and unity.”

In 2010, a small group met with City Public Art director Mary Altman to talk about the idea of creating a memorial that honored not only Biggers’ work but his dedication to “planting seeds” — developing young Black artists’ careers, like Ta-coumba Aiken, who worked on the original mural. The John Biggers Seed Project was born. Heather Doyle and Victoria Lauing with the Chicago Avenue Fire Arts Center jumped on board and discussed building a new kiln (one of the largest in the country) to create large-scale artwork in enameled steel and training other creatives to help in the process. Artists began working with more than 60 volunteers every week to prep and coat the steel in order to have it ready to install on the Olson Memorial Highway bridge.

But there were setbacks: The 2007 collapse of the I-35W bridge became the No. 1 focus for the city and the Department of Transportation. Changing plans for the bridge created more delays. Then, the global pandemic shut down all installation plans until this year. “Everyone worked together,” says Aiken. “There were hard times, like leaving [the Fire Arts Center] late at night and getting stopped by the police. But it’s amazing.”

“Losing the ‘Celebration of Life’ was an enormous loss for the community; it had to be made up,” says Altman. Artists like Aiken credit her with leading the push for the Seed Project to flourish, despite the obstacles. “It’s important to have this African imagery in the public realm,” she says, referring to Biggers and the works of many of Minneapolis’s Black artists. “This mural is bringing that back.”

The last enamel panel of the John Biggers Seed Project was recently set in place and the project was finalized in late September. “By educating people about African American art and community history, it cultivates a sense of place,” says Cummings, who grew up not far from the “Celebration of Life” mural. “It links the Northside and downtown. This project strengthens community identity and empowers artists to shape their environment at a time of city change with adjacent development.”

Aiken was a little more spiritual about his journey: “It’s like a phoenix rising. The ‘Celebration of Life’ never should have been torn down. But things happen for a reason. Now, there’s new life and new focus on what’s happening in our society.”