Aliases, entourages, Secret Service teams sweeping the halls: These trappings of a Hollywood thriller might seem out of place at a hospital, much less one in rural Minnesota. But the Mayo Clinic isn’t your typical medical center.

The sprawling Rochester campus has become the doctor destination for the world’s most famous figures over the past 130 years. The remote location does cause some grumbling. A young John F. Kennedy reportedly called it the “goddamnest hole I’ve ever seen.” And comedian Richard Pryor once cracked, “You know this shit is bad when you gotta go to the fucking North Pole to find out what’s wrong with you.”

And yet, Mayo’s sterling reputation has led heads of state, Hollywood elite and world-class athletes to flock to the so-called “miracle in the cornfield” for their most pressing health concerns.

Although stories of some of the institution’s most famous visitors — from baseball great Lou Gehrig to President George H. W. Bush — are enshrined in the clinic’s Heritage Hall, patient privacy reigns supreme at Mayo. So it comes as no surprise that many hospital-gown-clad appearances by the rich and famous have remained shrouded in secrecy. Artful Living went digging in search of some of the most riveting — and consequential — tales of celebrity medical treatment over the years.

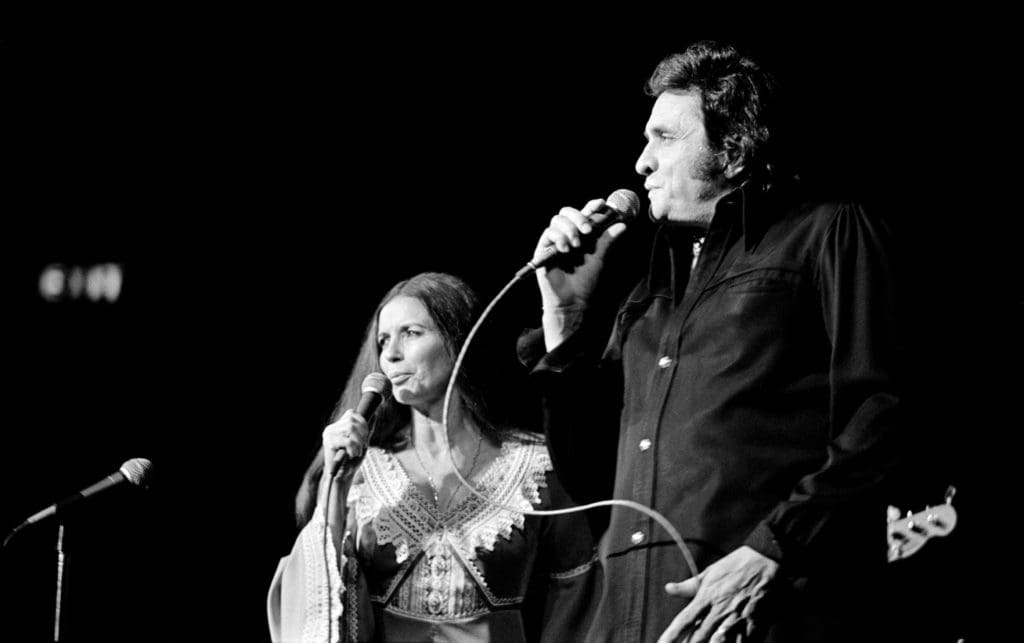

Johnny and June Cash

In August 1981, tens of thousands of faithful fans packed into a stadium in Calgary, Canada, to see Johnny and June Carter Cash perform. But unlike on other tours, the first couple of country music wasn’t headlining the multi-day affair. Instead, they were there to support Johnny’s good (albeit unlikely) friend the Reverend Billy Graham as he delivered the gospel on one of his famed preaching crusades.

But by the end of the two-day appearance, instead of riding high on God’s glory, Johnny was seriously ill. A private jet ferried the country crooner to Mayo, Graham’s hospital of choice. Doctors diagnosed him with an attack of bleeding ulcers, a potentially life-threatening condition. Luckily, he recovered quickly and was released after just four days.

That emergency trip wasn’t the duo’s only trek to see Mayo doctors. Two years later, the Cashes returned so June could undergo surgery for “benign” abdomen issues. “Nothing serious,” Johnny insisted to local reporters at the time.

June also turned to the Rochester clinic for help treating her anxiety. But the cause of her stress, it seems, couldn’t be cured by Mayo’s experts. “One of the doctors there who understood both of them pretty well told June, ‘Your biggest problem is being the wife of Johnny Cash — you’ll have to do something about that before we can do anything for you,’” longtime Cash bassist Marshall Grant told biographer Robert Hilburn.

Mayo doctors were also unable to save Johnny later in life, because they didn’t have the chance. When his health deteriorated following June’s death in May 2003, Graham urged him to return to Rochester for care. Johnny declined. “[He] didn’t have the strength to even consider it,” wrote Hilburn. He died just months later at the age of 71.

Clara Bow

Clara Bow couldn’t breathe. The famed flapper had spent the 1920s charming the masses, becoming one of the biggest stars of the (silent) silver screen. But beneath the gilded surface, Hollywood’s original It girl was increasingly ill and desperate for answers. And so, in December 1939, the 34-year-old boarded a train from Nevada to Minnesota in search of a cure. Claustrophobic and plagued with panic, she didn’t sleep for days.

Bow’s doctors back home had tried and failed to pinpoint the cause of her complaints, a mélange of maladies that included headaches, insomnia and chronic back pain. Just years before, a series of nervous breakdowns had ended her career. Her husband, actor Rex Bell, hoped Mayo’s experts could crack the case. Bow stayed for three weeks of tests and observations, but answers eluded her doctors. One, Frederick Moersch, gave the “delightful and cooperative patient” a clean bill of health. He dismissed her symptoms as being of “little consequence” and the result of “a personality problem.” On New Year’s Day, the starlet checked out.

But that clean bill of health was short-lived at best. Bow’s physical and mental health continued to deteriorate. In 1944, after her husband launched a congressional run, she tried to end her life. In a note, she declared that she preferred death to another turn in the spotlight.

Several years later, she checked into a psychiatric hospital in Connecticut. The diagnosis? Schizophrenia. Bow didn’t believe it. She fled and lived as a recluse until she died of a heart attack in 1965 at age 60.

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali was hungry for a comeback — and some cash. And so in the summer of 1980, just months after he had officially retired, the boxing champ’s team decided to stage one final blockbuster match. He’d go up against heavyweight titleholder Larry Holmes, a skilled boxer in the prime of his career. It would be Ali’s first fight in two years.

With reports swirling about Ali’s deteriorating health, including a potential kidney condition, Nevada boxing officials insisted he get a doctor’s sign off before returning to the ring. He agreed, so long as he could go to Mayo for his care.

In late July, he checked into the Kahler Grand Hotel, the inn of choice for the hospital’s high-end guests, ahead of a series of exams that included a brain scan. Ali was so confident about his ability to fight that he held an impromptu press conference in the hotel lobby.

But the results were mixed at best. One physician found the boxer in “excellent general medical health,” while a neurologist documented troubling symptoms. Ali admitted that basic tasks like touching his finger to his nose and hopping on one foot proved difficult. But even with those issues, Mayo doctors declared him fit to fight. “A staff of seven of the world’s best doctors gave me the green light today,” Ali boasted to reporters, “and that proved all the liars wrong.”

And so on October 2, 1980, the Greatest of All Time stepped into the ring at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, where promoters had built a 25,000-seat outdoor arena to meet ticket demand. Millions in bets were on the line. The match was dubbed the Last Hurrah, but for Ali, it might as well have been called A Giant’s Fall.

Holmes clobbered the battered former heavyweight, landing punch after punch. After 10 brutal rounds, Ali’s trainer called an end to the fight. Sylvester Stallone likened the scene to “watching an autopsy on a man who is still alive.” Ali walked away with loads of cash, but the damage was done. When he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1984, many blamed that fight for exacerbating his condition.

Helen Keller

As her historic 1937 voyage to Japan came to an end, Helen Keller and her companion, Polly Thomson, traveled to Mayo for their annual checkups. For years, the famed author and activist, who lost her sight and hearing as a young child, had complained of stomach pains. A routine physical uncovered a potentially serious cause for her discomfort: a diseased gallbladder.

Doctors recommended removing the organ. Keller agreed, writing to a friend that she thought it was best to “get rid of this obstacle to continued health and usefulness” while she was strong and well.

Her one concern? Having to take time off work as an international advocate for the blind and deaf. “The only shadow,” she wrote, “is my distress at the thought that I shall not be at my post in October.”

Still, Keller reveled in her good fortune to stay in the “sweet, quiet, tree-shaded town.” “Everyone at the clinic is so kind and the atmosphere is so cheerful and wholesome, it heals and strengthens us,” she wrote. She recounted being attended to by some of the clinic’s top doctors, including founding physician Charles Mayo himself. “His noble presence and modest simplicity reminded me of Einstein,” she noted. “Each day, I realize more fully what a worldwide beneficence the Mayos are spreading through the clinic.”

And that kindness went both ways. Keller developed a reputation as a beloved patient as she forged close relationships with doctors and nurses. She was also known for being a gracious guest at local gatherings. At one memorable dinner party, she stood at the piano for a child’s impromptu performance so she could feel the vibrations of the music. And during World War II, Keller was known to make an appearance at farewell affairs for local residents departing for service, taking the time to wish each person good luck.

Ernest Hemingway

On November 30, 1960, Ernest Hemingway checked into Saint Mary’s Hospital (part of the Mayo campus) under a false name. At the time, the Nobel Prize–winning author was one of the world’s best-known writers, so discretion was of the utmost importance. But news of his month-long stay didn’t remain secret for long. Rochester residents spotted Hemingway around town, and soon local reporters were badgering the clinic for information.

Eventually, Mayo released a brief statement saying he was being treated for high blood pressure. But news reports and biographies suggest the real reason for his visit: a bout of severe depression. Doctors prescribed electric shock therapy for his mood disorder and also treated him for diabetes and an enlarged liver.

The writer charmed his caregivers and, at times, seemed to enjoy his stay. Like many famous patients at the time, he was known to socialize at doctors’ homes, where he would sing French and Italian songs alongside wife Mary. “[He] had happy times,” one physician told a biographer. “Although I saw him when he [was] ill, he still had a great, great sense of humor.”

In January 1961, Ernest was released and sent home to Ketchum, Idaho. But he was far from cured, and the rounds of electric shock therapy were said to have lingering effects on his memory.

Within three months, a severely depressed and suicidal Ernest returned to Rochester. Once again, doctors put him through electric shock therapy. Although he was under close supervision, the writer was allowed to leave hospital premises. Residents spotted him at a local watering hole and at the target range. By late June, doctors cleared him for release, and Mary reluctantly brought him home to Idaho. He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound less than a week later.