Jessica Lange is all about the outlandish and the grotesque. She likes her acting roles theatrical in the extreme, the more vaudevillian the better. During her 38-year career, she has played the angel of death, a sociopathic witch, a murderous seductress, a hypersexual gothic queen. Her characters have been lobotomized, electroshocked and stabbed in the neck.

But as histrionic as her film and TV career has been, it doesn’t compare to her life before she was an actress, when she was unknown and young and roaming the earth with American aristocrat Danny Seymour and photographer Paco Grande. For eight years from 1968 to 1976, Lange lived the life of the artiste bohémien. She got tear-gassed in Paris during the 1968 student revolution. She drank in cafes with fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld, who favored high heels and furs for his daily outings. She pantomimed in Washington Square Park in New York City for loose change.

Here is the mostly untold story of Jessica Lange’s bohemian life, before she ever set foot on a movie set.

Jessica Lange was born on April 20, 1949, in Cloquet, a town most famous for being the site of a massive drought fire that killed 453 people in 1918. Her father was a restless wanderer, constantly rooting around for something — anything — better. He moved his brood around more than 18 times during her childhood, seeking this job or that: railroad worker, salesman, teacher. Her mother was the emotional glue of the family, a relaxed, jovial woman who learned Finnish from her immigrant parents and spoke it on the phone with her aged mother.

By the time Lange was graduating from high school in 1967, Cloquet was deflating and depopulating — “a worn-out little mill town,” as she described it in 2008. She escaped to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis with plans to study painting. She tried to get into the campus culture and even attended some Vietnam War protests. But she felt strangely removed. Speaking with a London Sunday Times writer in 2008, she recalled having “a kind of yearning” during those first months at the U. “But I didn’t know what I yearned for,” she mused.

In the spring of 1968, Lange took a class with a young photography instructor named Jay Hines. It was this class that opened the door to her new adventuresome life. The studio-arts department was a favorite hangout for two young photographers, Francisco “Paco” Grande and Danny Seymour. Grande, then 24, had been born in Madrid to an eminent physiologist and his pharmacist wife. Though descended from a long line of distinguished doctors and scientists, he had wanted to be a photographer since he was 12 years old and saw Edward Steichen’s exhibit The Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art. His pal, the 23-year-old Seymour, was the son of poet Isabella Gardner and Russian show-business photographer Maurice Seymour and a distant relative of multimillionaire art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, whose tremendous wealth flowed from linen, produce, railroad, milling and mining investments. Friends for years, the two bonded over their shared interest in photography.

When Grande laid eyes on Lange for the first time, he was struck to the core. He related the story in a 2013 interview with Peruvian writer Vladimir Herrera: “A friend of mine told me he had a beautiful girl in his photography class. And I went to see, and indeed, there she was, the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. And I pursued her like a missile. I convinced her to drop everything, to leave school, to leave her family and come away with us.”

That “us” of course included Seymour, who was plotting an adventure to Europe. That February, the three of them left the country, bringing along an entourage of artists. Seymour rented a house in Spain for the crew and took Grande and Lange to stay with his half sister, Rose Van Kirk, who was living with noted music director Anzonini del Puerto. They took still photos of the Andalusian peasants and the homes they had fashioned out of caves.

In May, they went to Paris to see the cultural revolution firsthand, but the chaos and violence were more than they had bargained for. “Hundreds of people had parked near the Arc de Triomphe and just left their cars to make a blockade,” recalls Grande. “People had taken chainsaws and piled up tree limbs at the big intersections. All the major arteries of the city were cut off.”

The crew parked on the Rue des Saints-Pères near the city’s medical school. All around them were med students trying to treat the bloodied protesters. “I tried to stay away,” says Grande, who was particularly disturbed to see the French police firing water cannons at a group of WWI vets. “But every day Danny and Jessica went to see what was going on and came back hours later smelling of tear gas.”

In the middle of the chaos, Lange and Seymour met a toothless street peddler named Ralph Levene who was mad because the protest was hurting his business. “He would yell at the protesters, ‘Go home so your mommies can tuck you into bed,’” Grande remembers. Seymour told Levene he would buy him new dentures if he came away with them, so the four of them — Lange, Grande, Seymour and Levene the street peddler — piled into a secondhand Land Rover and made their way to Amsterdam.

In the Netherlands, they met Londoner Peter Wynne-Willson who was on tour with Pink Floyd as the band’s lighting designer. “I was standing on a cobblestone street in Amsterdam, and some guy pulls up on a motorbike and says ‘Hop on’, so I did,” remembers Wynne-Willson. “We went to this artist’s loft, and there was Paco surrounded by all his courtiers. Paco yelled over his shoulder, ‘Hey, Jessie, come in here and look at this barefoot hippie we found.’”

After their European adventure, Lange, Grande and Seymour moved to New York, where they lived with performance artist Ellie Klein at Broadway and Prince Street. They got to know aerialist dancer Batya Zamir and her experimental artist husband, Richard Van Buren. Lange and the others put on a mime performance at 23rd Street and Union Square called “The Mime & Medicine Show.” Grande remembers that for the show, Klein put sparkles all over his hair and beard, and outfitted him in color-splashed white overalls with metal snaps down the inside of both pant legs. “It was supposed to be silent, but the metal snaps on my overalls kept clicking,” he says. After that, the threesome moved to a loft at Broome Street and West Broadway but got kicked out for too many noise complaints. They put on a second mime performance, “Mondo Frico,” at a loft on Leonard Street rented by artist Alan Shields.

At the end of 1968, Seymour used some of his family money to buy three lofts at 184 Bowery, a former SRO hotel boarded with plywood and marred with graffiti. He took up residence on the top floor; Lange and Grande set up shop on the sixth floor; and Seymour gave the third loft to Swiss photographer Robert Frank, who just had been kicked out by his first wife. The building quickly became a hangout for young photographers interested in documentary surrealism, such as Danny Lyon and Larry Clark. Lange dabbled in photography and conceptual art, painting tiny Formica boxes.

“But by the summer of Woodstock, we were really sick of New York,” says Grande. The two sold their loft, bought a van and drove to California. In San Francisco, they hung out with blues musicians Michael Bloomfield and Mark Naftalin. In San Rafael, a mutual friend introduced them to some drug smugglers from Minnesota who claimed to have pulled off a major operation. Grande dubbed the shady characters the Mystic Mafia of Minnesota, or 3M, but he was intrigued.

In January 1970, he and Lange went to Mexico, and Grande boarded a twin-engine, nine-passenger Cessna 402A with 40 23-pound boxes of very fine marijuana. “My big idea was to make a documentary of a drug-smuggling operation,” he says. But during the flight, there wasn’t enough oxygen in the plane, and both Grande and the pilot passed out. When the captain came to, he had just enough time to land the plane on its belly at the tiny airport in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The pilot made a run for it and wasn’t caught for six months. Grande was nabbed right away and thrown in “the same jail where they filmed Easy Rider,” he says.

His distinguished parents were appalled but jumped into action. “My mother came and cried in Spanish, and then Jessica came and cried in English, looking beautiful,” says Grande. On his lawyer’s advice, he got a straight job glazing doughnuts in Albuquerque, and he and Lange got married back in Cloquet on July 29, 1970. For their honeymoon, they lived on Seymour’s sailboat off Shelter Island in New York during August 1970.

That fall, while Grande made regular visits to his probation officer, Seymour put together the cast for Home Is Where the Heart Is, a short film about loneliness and drug use. Lange played a waitress, her first onscreen performance. After that, the crew became enamored with Marcel Carné’s 1945 film Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise) about a tragic love between a theater mime and a worldly actress.

With Klein’s urging, Lange decided to go to Paris to study with master pantomimist Étienne Decroux. She left without Grande, who was still on probation and couldn’t leave the country. She rented a place on Rue des Rosiers in Le Marais across from the famous Jewish deli Chez Jo Goldenberg. She got a tattoo of a quarter moon on her hip and adopted a pet bird.

Back in the states, Seymour and Grande were entertaining John Lennon and Yoko Ono, who were making the film Fly at Seymour’s loft. “Lennon wanted some heroin, and Danny was trying to find it for him, and I really think that was when Danny started shooting heroin,” says Grande. “To Danny, musicians were the highest form of people, even more than artists.” Ono had little Styrofoam containers with black houseflies, and she gave them little bursts of carbon dioxide to get them drunk. Grande remembers all the naked women auditioning to be in the film and Lennon playing “I Don’t Want To Be A Soldier” on a guitar gifted to Seymour by bluesman Michael Bloomfield.

In early 1971, Grande got the charges dropped and his passport back and subsequently chased Lange to Paris. She kicked him out after a few months, though, and he ended up rooming with a mime and a saxophonist from Algiers. By August, the couple had made up, and he traded his Leica camera for a beat-up Volkswagen. They stayed for a month at the Grande ancestral home situated in a small village in northern Spain and dating back to the 16th century.

When they returned to Paris, Lange got serious about mime. Her classes were held in the basement of a small brick house in Boulogne-Billancourt. Decroux was 73 years old by this time but still as feisty as ever. The narrow basement had a single theatrical light and a pair of limp white curtains strung at one end. “Never forget,” the instructor would say, “the first Christians worshipped in catacombs!” Sometimes Decroux taught in flannel pajamas, a terry-cloth bathrobe and bedroom slippers. That or a pair of black boxing shorts and a long-sleeve, collared black shirt, his white-gray hair slicked back.

Decroux was tempestuous. He despised theater with words: “The poets’ lines follow one another inexorably like the trucks of a freight train. The poor actor can’t squeeze himself in between them.” He abhorred dance: “Dance is the weakest of the arts, the one that can’t exist alone, like potatoes, the weak vegetable, a parasite on meat!” Most of all, he loathed 19th century pantomime, like the kind revitalized by his former student Marcel Marceau.

What he loved — and believed himself to be the only truly competent teacher of — was corporeal mime, a style invented by Jacques Copeau before World War I. Nineteenth century pantomime emphasizes expressive hands and face, and follows a logical, often funny story line. Corporeal mime, by contrast, focuses on the trunk of the body and is very abstract, often with no story line at all. On Friday evenings, Decroux would lecture his students then demand impromptu performances. His commands were famously cryptic. “Portray a thinker,” he might say. “After a while, you will become thought. Emotion leads to motion, thought begets immobility. Begin!”

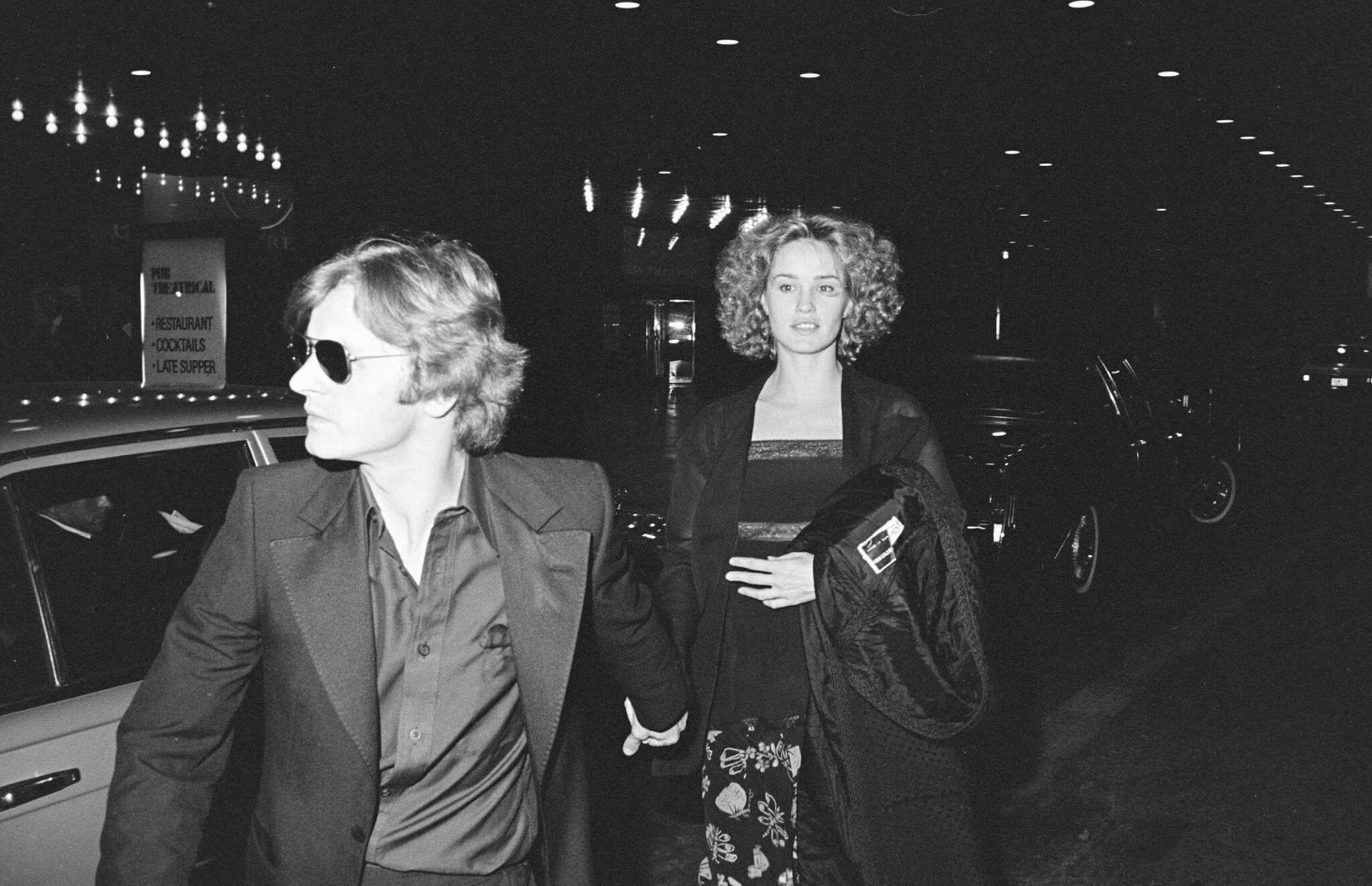

Fashionable Americans started arriving in Paris in droves. Andy Warhol showed up in 1970 followed by Paloma Picasso. Models Grace Jones and Pat Cleveland arrived, as did Texan Jerry Hall, with her waist-length blond hair. The center of this Parisian monde was the private salon of Puerto Rican artist Antonio Lopez and his partner, Juan Ramos. The first time Lange went out on the town with Lopez, he dressed her in a gold lamé evening dress by Karl Lagerfeld. It would be her first time wearing couture. “In many ways, Paris was hotter than New York in the seventies,” says Grande.

In the summer of 1972, Lopez bought a Kodak Instamatic and started taking pictures of the new Paris haute bohème. Lange became one of his favorite muses, tossing around her blond curls and seductively smoking cigarettes in neon lighting. Lopez pronounced her name the French way, L’Ange, to make it sound like “the angel.”

That year, Lange and Grande broke up again, and he went back to Minnesota to live in an artist commune near Lake of the Isles. Seymour went on the road with the Rolling Stones, acting as the band’s cocaine hookup and the sound guy for Robert Frank’s ultra-grainy 16-mm documentary Cocksucker Blues. Grande went to see his old friend in Chicago and was stunned by how bad Seymour looked, completely strung-out on heroin. “He was floor decoration,” he recalls. “But it’s not like I could say anything to him, because way back when, he had admonished me for trying heroin.” The Stones brought Seymour, Grande and Frank to a party at Hugh Hefner’s infamous bunny pad at 1340 North State Parkway, where they saw Stevie Wonder carousing with the Playboy bunnies.

Seymour talked about getting clean, maybe going for a sleep cure or getting a blood transfusion. But when the Stones tour ended in October, he bought a 38-foot wooden yacht for $70,000 cash and subsequently disappeared. Lange and Grande met up in New York and immediately flew to Colombia to look for him. “At the beginning, we were worried, but not too worried,” says Grande. “We knew he would turn up.” After one of the largest manhunts in maritime history in the spring of 1973, the search was called off. The yacht was found, but Seymour’s body never was. He wasn’t officially declared dead until 1981, the year Lange and Grande ultimately divorced.

After the trauma of losing their closest friend, the couple got back together and rented a small fifth-floor walkup in Greenwich Village. She started waitressing at the Lion’s Head Tavern and taking classes on Bank Street with a burly, bald acting coach named Herbert Berghof, who had been a close friend of Marlon Brando. Lange fell in love with acting. “It was the first thing I landed on that felt complete,” she told the London Sunday Times Magazine in 2008. Grande by this time was mostly blind from a genetic disorder called retinitis pigmentosa.

On Sunday afternoons, she would mime in Washington Square Park for loose change while he took pictures with his Nikon F3 and drank vodka out of a paper bag, accompanied by his seeing-eye dog. They got to know a lot of the other buskers and a few drug dealers who pretty much lived in the park. In 1974, Lange signed on with Wilhelmina Models because she had heard that movie directors were hiring models rather than trained actresses for choice parts.

Her strategy worked. In 1976, Dino De Laurentiis called the agency looking for a potential scream queen for a remake of the 1933 classic King Kong. Someone at Wilhelmina vaguely recalled that Lange had studied acting. Within 24 hours, she and two others were on a plane to California. During her screen test, the director cried out, “I found my Fay Wray!” And that was that. Soon Lange was costarring with a 45-foot-tall mechanical gorilla. Her bohemian life was over.