Photography by Mary Jo Hoffman

Minneapolis chef Alex Roberts has run the iconic Alma restaurant for almost 25 years, is a James Beard Award winner and, it turns out, possesses a remarkably accurate first serve wide to the deuce side. Sommelier Nicolas Giraud, who has worked for Alain Ducasse in France and Gavin Kaysen in Wayzata, is sneaky quick, with a nearly un-playable drop shot. Stephanie Shimp, owner of Blue Plate Restaurant Company, has a crackling two-hand crosscourt backhand. And Peter Bian of Saturday Dumpling Club can serve a tennis ball 100 mph. I only know this because I too am a member — informally, as we all are — of Hospitality Tennis.

It began with a chance meeting at Norseman Distillery between Bian and Erik Eastman of Minnesota Ice. Some Ping-Pong was played. Some dumplings were bought. Bian introduced Eastman to a spectacularly talented local tennis pro, Mohanad Alhouni, and soon enough, a tennis friendship blossomed.

To understand what happened next, it helps to know a bit more about Eastman. He’s one of our most talented mixologists and purest hearts. Over the past decade, he has managed to fold much of the local food, wine and spirits community into a warm, long-armed embrace through his unlikely profession: selling ice to Minnesotans.

After he saw the light — that day across the net from Bian — he began evangelizing the joys of tennis to all who would listen. Coming from anyone else, this might have amounted to the mere patter of a good salesperson, but when Eastman spoke, people listened. And not only listened, but believed. And joined.

Chef Thomas Boemer, co-owner of Revival Smoked Meats, joined us with his howitzer serve. David Fhima, executive chef of Maison Margaux, brought his elegant slice backhand. And Joe Kotnik, founder of Rootstock Wine Co., came with his nimble footwork.

In this setting, the high standards, the narrow margins, the bad Yelp reviews — all the daily pressures and judgements that await anyone attempting to make a living in the food and wine world — fell away for an hour or two. Our regular Sunday gatherings of professional rivals in a difficult business ended, without fail, with a congenial exchange of hugs, best wishes and gratitude that such a thing existed.

The Minnesota tennis year is a hard-court affair, indoors or out. Northern winters aren’t kind to grass and clay surfaces. But last summer, we all watched, mesmerized, as tennis’s newest superstar, 20-year-old Spaniard Carlos Alcaraz, captured the Wimbledon gentlemen’s singles title in imperious and impeccable style. And like kids who throw the pigskin around at Super Bowl halftime or play catch between World Series innings, we ended the Wimbledon fortnight hungry to play tennis on grass.

As it happens, just outside of Charles City, Iowa (about three hours south of Minneapolis), there’s a modest farmhouse on a dusty gravel road, surrounded by what looks like most of the state’s 12 million acres of corn. Next to the house, a picket fence encloses a former cattle feedlot that’s now an unlikely sight: a pristine, perfectly flat, emerald-green, chalk-lined grass tennis court.

This is the All Iowa Lawn Tennis Club, built by an obsessive gentleman (one uses that term in the realm of grass courts) named Mark Kuhn. He grew up listening to BBC Wimbledon broadcasts on a short-wave radio in the 1960s, dreaming of someday creating his own Centre Court. By 2003, he managed to pull off that far-fetched feat, and today, his manicured kingdom is available by reservation to anyone willing to make the drive and pay the $480 daily fee (100% of which supports his nonprofit, the All Iowa Lawn Tennis Club Foundation).

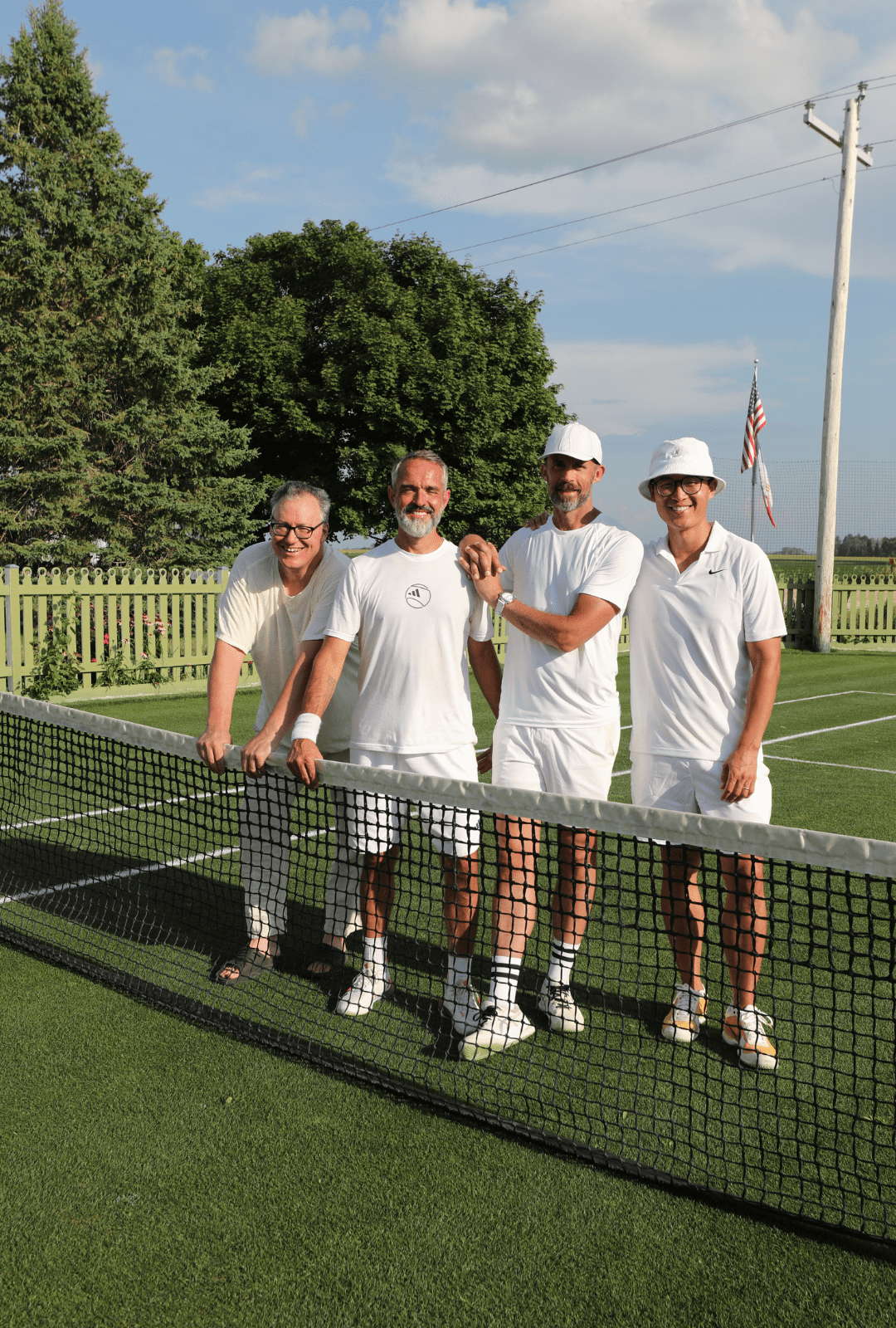

So it was that four members of Hospitality Tennis — Eastman, Bian, Roberts and I — arrived in Charles City on a 90-degree August morning, with the court to ourselves for the day.

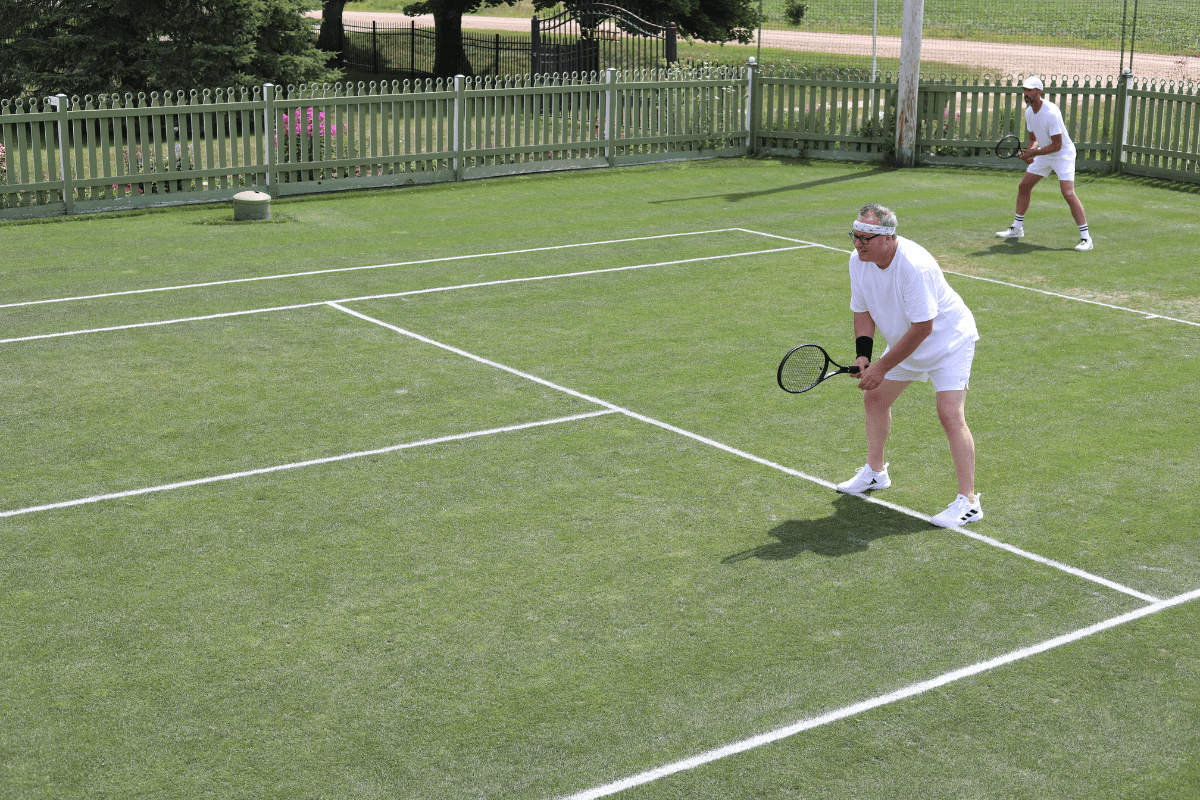

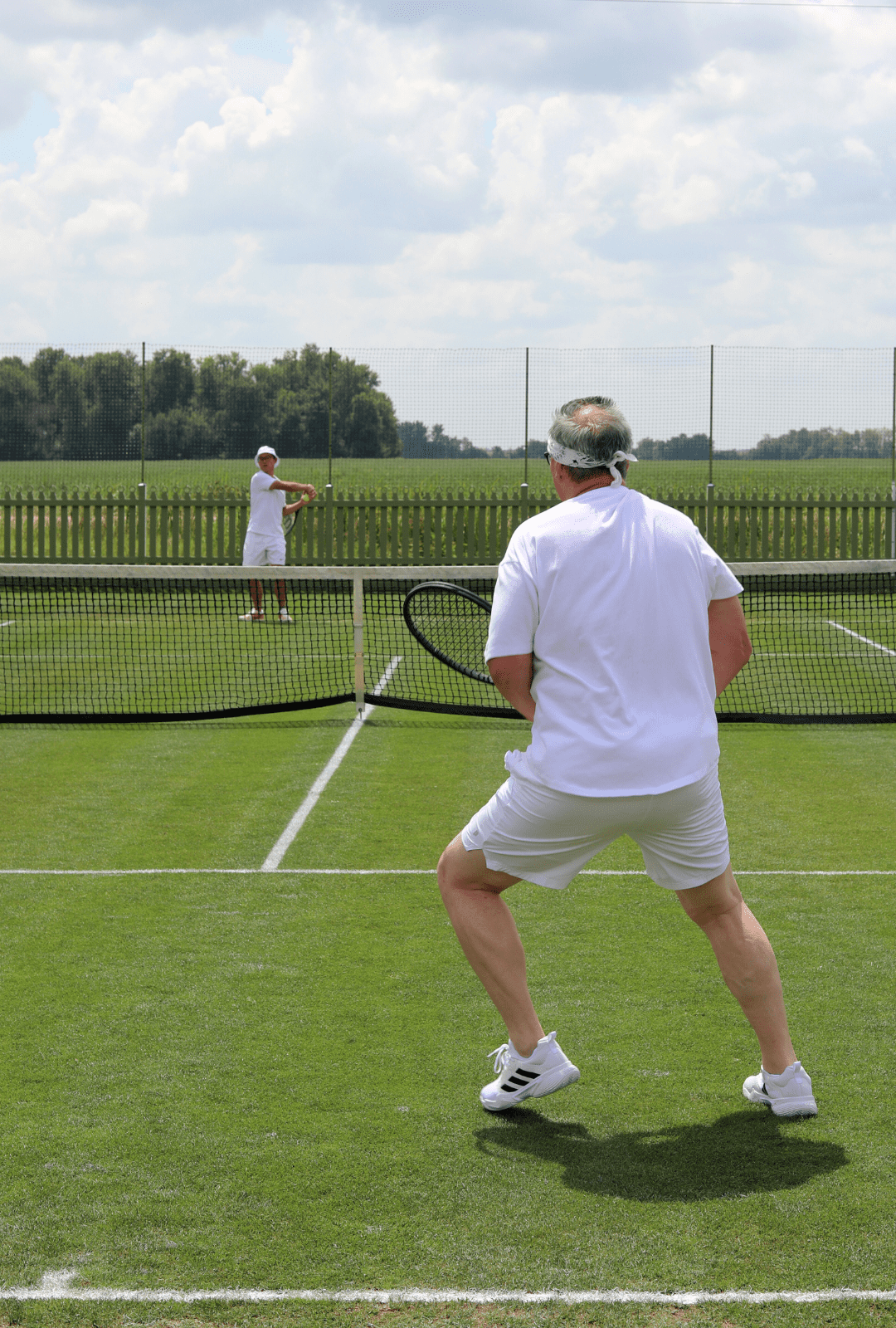

Well, not entirely to ourselves. Kuhn, smiling under his Stan Smith mustache, was there to host, talk tennis, offer ice water and invite us into the air conditioning for a spell. He had surely seen far better players grace his court, yet he remained encouraging and commiserative as we sweated under the hot summer sun in our tennis whites (bought specifically for the occasion) and learned, by trial and many errors, how to judge the bounce of a tennis ball off a 7/16-inch carpet of mown bentgrass.

Over lunch, we learned that Kuhn’s quixotic efforts to bring grass-court tennis to Iowa had captured the imagination of the Wimbledon staff and that he had made several visits there, first as a grounds crew intern then as an honorary court attendant. He regaled us with insider stories as we ate Roberts’ fried-chicken sandwiches (which he had prepared that morning at dawn, because that’s who Alex Roberts is).

It had been clear almost from the start — from our first steps out of rural Iowa, through the looking glass and into Kuhn’s private dominion — that the day wasn’t solely about tennis.

The court began as a boy’s implausible dream but was completed as a family project. Kuhn spent long hours with his sons, Alex and Mason, cutting sod, picking rocks, laying drainage tile and individually cutting, with a jigsaw, the 628 pickets for the bordering fence.

Then in 2016, Alex took his own life at the age of 34. Mark hadn’t seen it coming and, in some sense, has never recovered. But in the way that the smallest daily habits can help get us through the worst of our grief, it seems that the demands of the grass court — the constant tending, the reassuring geometry of white chalk stripes on 10-millimeter blades of grass — provide him with a form of succor, however insufficient, and a connection to his son, however imperfect.

That summer day, we talked about the comforts of tennis, which is sometimes just a game, and sometimes more than a game. And about the comforts of sharing a meal, which is sometimes about food, and sometimes about more than that.

The four of us returned to the court for the afternoon in a different frame of mind, counting our small wins and losses on the scoreboard amid the larger losses that surrounded us, on a tennis court that was not only a tennis court, but also a memorial.

While the sun set over the cornfields and the towering wind turbines, we gathered in Mark’s living room, where he served us strawberries and cream, washed down with wine that Bian had saved for just the right occasion, among just the right people.

In its most important incarnations, hospitality is not really an industry, nor is it simply a way of tending to the wishes of patrons, although that work can approach a kind of sublimity when done just right. Fundamentally, hospitality is about attention and comfort, about tending to the deeper needs. And it can, now and then, be about recognizing when a moment has opened up into something new.

As we prepared to climb back into our cars in the vaguely lonesome and crickety darkness, Mark suggested we make a stop in town on our way home and join him for the summer’s final Party in the Park, where we could share a beer and some tacos and listen to a pretty good Doors cover band.

We all agreed — kind of relieved that the evening wasn’t yet over — and spent an hour in Central Park with Mark and some of his neighbors, a few blocks from Trinity United Methodist Church, Mara bridal shop and the Fullerton Funeral Home. Just southeast of us, on the Cedar River, a white gazebo overlooked a memory garden designed by a Charles City resident who had lost her son in childbirth, started a support group for families whose children had died and wanted to create a place of solace for all grieving parents.