“Train! There’s a train coming!” Shouts and yells undulate across the hobo jungle in a wave, sending swarms of people sprinting toward the tracks to wave their caps at an oncoming locomotive. I’m sitting at a picnic table eating mulligan stew across from a grizzled old hobo named Redbird. He is covered in tattoos and has been reading me poetry from his journal, where he copies in immaculate penmanship poems about travel. Merely from hearing the rumble, Redbird knows exactly what kind of train is approaching and where the best place to hop on might be. He knows the grades and distances of the track between the Britt station and other stations crisscrossing the continental United States like an intricate steel spiderweb, paying homage to a now-distant age.

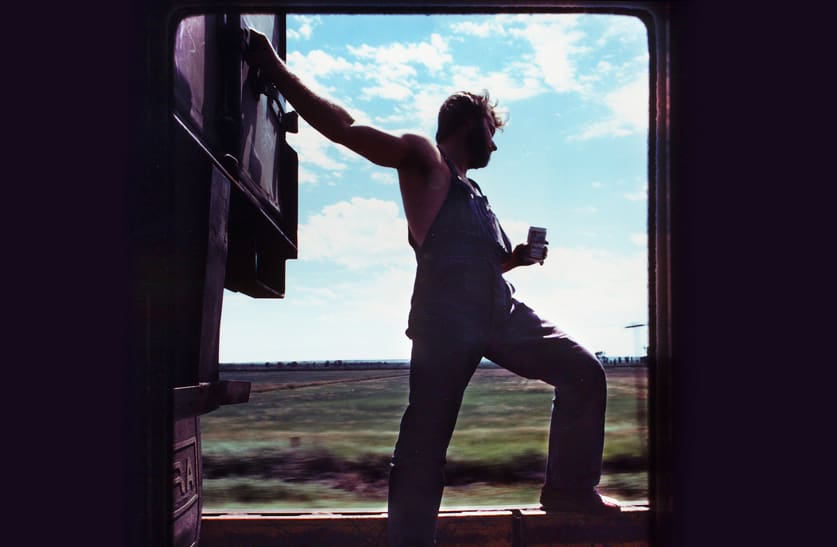

Hoboes wave enthusiastically at the train until it passes. Its whistle resounds as the conductor tips his hat to the only other group of people in the world that loves freight trains as much as he does. The train passes, and the magic is over. We return to our stew. The whistle gives way to the metallic clinking of silverware and steel-toed boots as the train cuts across the open fields, plowing onward to its next destination. The moment epitomizes the hobo way of life: adventure, fantasy and the grandeur of the open road contrasting with the stark reality of life on the tracks.

I’m at the National Hobo Convention in Britt, Iowa. The annual gathering coalesces hundreds who flock from across the country to celebrate their heritage and their history. If you didn’t know hoboes still existed, you’re not alone — but you’re simply not looking in the right places. On your commute across the I-35W bridge or your pause along the Wayzata railroad tracks, you may very well be crossing paths with one who chooses to ride under the radar.

When I first began my research on hoboes years ago, well-meaning friends would offer to introduce me to homeless people on their street corner. This association is a common misperception. Indeed, hoboes are unlike any other itinerant population in existence; the key to being a hobo is that a hobo chooses his identity. Ask any hobo, and she’ll tell you emphatically that hoboes, tramps and bums are nothing alike. Hoboes travel across the country by hopping onto trains (although other modes of transportation are also acceptable), but crucially they work for their living, performing seasonal labor and taking on odd jobs. Tramps travel, either via rail or hitchhiking, but they rarely work (and instead often beg). Bums evade both these categories, neither traveling nor working. The topos of the hobo is historically rooted, rising from a group of wanderers who gradually created an entire subculture reliant on train travel, replete with nicknames, signs and symbols, and distinct language, literature and music.

Hoboes remain one of the most pervasive subcultures ever evolved from American homelessness, partly because they cultivate a distinctly American ethos of freedom and independence. Hobo culture transforms the country’s transportation infrastructure into a veritable playground and rejects the perceived banality of middle-class existence for a life of adventure, albeit one often marred by danger, poverty and sadness.

History of the Hobo

Two waves of hoboes evolved into the modern hobo. In Knights of the Road: A Hobo History, Roger Bruns notes the crucial coincidence of the Civil War’s end with the birth of the railroad: “The Civil War had turned thousands of boys into disciplined foragers, resilient, hardened, able to find food and shelter in all conditions, proficient in the use of the railroad.” These disenfranchised boys returned home from war, but most found that no home was left. So they took to the road, hopping on a newly extensive network of trains to find work and see the world.

Nobody really knows where the term “hobo” came from, but Bruns explains that “Jeff Davis, longtime hobo king and showman, claimed that the word referred to ‘hoe boy,’ a term used in the 18th century for a migratory agricultural worker.”

The Great Depression produced a second wave of hoboes who used the rail system to find seasonal labor, but many never returned home. Entranced by the freedom and excitement of life on the road, “hobohemia” (a term coined by hobo scholar Todd DePastino) lured Americans out of suburbia and onto the rails.

The itinerant population gradually created its own community and culture, which found its nexus in the hobo jungle. “Usually located just outside of town, near running water and the tracks, the jungle served as pub, restaurant, hotel, literary gathering place and information center for traveling hoboes,” writes Bruns. They would congregate each evening and make mulligan stew, a pleasant euphemism for a combination of whatever ingredients each person happened to contribute to the communal soup.

Tourist Union No. 63 was created in the early 19th century to help hoboes avoid being arrested for vagrancy, and it remains one of the oldest continuous-running unions in the United States. The Hobo Museum (also in Britt), Hobo Olympics (now in its sixth year) and soon-to-be-founded Hobo Church all serve the members of their namesake community.

Hoboes even have their own lexicon, an elaborate system of communication that lets others know where it would be safe to rest their heads. In the Hobo Museum, a denim tapestry made by a hobo named Texas Madman functions as the most iconic dictionary of hobo symbology. Everything from “Good Road to Follow” to “Cowards Will Give To Be Rid of You” to “Easy Mark Sucker” would be scratched in yards and roads as messages to the rest of the community.

Sometimes being a hobo is temporary. Other times, these nomads grow up along the tracks and find it difficult to desert the way of life. Lore recalls stories of elderly hoboes escaping their nursing homes to hop a freight, unable to leave the rails behind. The wanderlust was in their blood, and polite society had become unbearable.

Riding the rails is historically fraught with danger, not only from law enforcement but from within the hobo community. For Gilded Age and Depression-era hoboes, starvation and exposure to the elements were common causes of death. Threats came from fellow travelers, as well.

“There are many stories of boys kidnapped by force or lured into concubinage, induced to beg for money, food and clothes for their captors, and sexually molested,” notes Bruns. Train companies, of course, historically have been no friend to the hobo. Still today, arrests by railroad police (known as “bulls”) are common. And as one might expect, the hobo community has its fair share of mental illness, substance abuse and suicide.

The National Hobo Convention

The convention is full of firsts for me: I’ve never been offered miscellaneous beverages from unmarked milk jugs. I’ve never witnessed a cow-chip chucking contest or a toilet-bowl race. I’ve never had a source with a name like “Connecticut Shorty.” “Shorty” is not her birth name, of course. It’s her hobo moniker, and it’s deeply important to her identity as a hobo. These names are simple yet colorful and descriptive: the famous Steam Train Maury, the late celebrated poet Iowa Blackie, librarian Bookworm Bonnie, Joey Bag o’ Donuts, Fry Pan Jack, Pistol Pete, Mountain Dew. Bestowed by a more seasoned hobo, these designations are worn like badges of honor. During my weekend in Britt, the closing ceremony includes conferring an adult name on a teen girl who isn’t particularly pleased with the hobo moniker she’d received at birth: Droopy Diapers.

The hoboes I meet in Britt are fiercely proud of their history and are dedicated to carrying on the tradition of the ’bo.

They wear steel-toed boots, which are necessary for hopping trains without losing a foot, and the younger hoboes don loose-fitting cargo pants and vests. New Age hoboes, referred to by the ancients as “young-uns,” reject the traditions of past generations, carrying smartphones instead of rucksacks.

For the most part, the hoboes I meet are welcoming and happy to share their stories. Former hobo king Luther “the Jet” Gette tells me he took an Amtrak here from Pennsylvania because he’s too old to hop freights any longer — though he still is tempted when he sees one pass by. Sunrise, a former hobo queen, explains what it’s like to travel as a single female out on the road; it’s about as safe as you’d imagine. She finds a male companion or rides up front with the train conductors when they let her.

I only experience one queasy moment, in which a hobo picks me out of the crowd. Not because of what I’m wearing, but because of my teeth. They’re white and straight from years of braces, which leads him to ask if I’m a “rich little bitch.” He stares at me as he spanks his dog because “bitches deserve to be spanked.” It’s fairly disturbing. For me, this moment cements my understanding of the hobo experience, which is one of dichotomies. There’s adventure, camaraderie and joy, but they simply are inseparable from danger, instability and terror.

Minneapolis: A Hobo Hub

In some cases, these hoboes aren’t disenfranchised and aren’t as far from our daily lives as we might imagine. At the convention, the vast majority of attendees traveled from Pennsylvania or somewhere in the North. Known for its Minnesota Nice even among ’bos, Minneapolis in particular functions as a centralized hub for hoboes.

In fact, if you live in Minnesota, one of these hoboes may very well be your neighbor or your child’s professor. Take the late Todd “Adman” Waters. A successful advertising executive by day with a stunning Lake Minnetonka home, he spent more than 40 summers riding freight trains across America.

Why did he become a hobo? Well, as he told writer Matt Stopera before his death last July, he had always done it. “He hitchhiked up to Cheyenne, Wyoming, but got arrested,” explains Stopera. “As soon as he got out, he jumped on a train. That night, he saw the most beautiful sunset he’d ever seen and thought to himself, “Fuck, I’m gonna do this forever.” And as it turned out, the hobo way of life was in his genes: After Adman had been a hobo for decades, his father gave him a packet of postcards from his grandfather, who, unbeknownst to his grandson, had been a hobo during the Great Depression.

“Todd fit well in both worlds,” says his wife, Dori Molitor. “He lived an entire life here in what he called ‘polite society,’ but then he could switch to a world of hoboes and travelers.”

For his family, his excursions were simply part of who he was. “When we were growing up, every summer, he was gone for four to eight weeks,” explains their daughter, Alexandra. “We knew it wasn’t normal, but it was always a grand adventure for us kids. It was always exciting when he was rolling his pack on the kitchen floor. I wanted to go with him from the time I was 7 years old.”

Adman would leave with his pack, an old newspaper bag, a gallon milk jug for water, and very little money, “$20 or so to get him to the train station,” says Dori. “He didn’t take a cell phone because he said, ‘The more you take, the less you experience.’ He would call with his three quarters every so often, and we’d talk to him for as long as we could.”

Did Dori ever think of asking him not to go? “Never,” she says emphatically. “At our wedding, numerous people asked, ‘Are you still going to let him ride the rails?’ Of course! He had done it before I knew him, and it was so much a part of who he was. We got married, we had babies and he still went every single year for 40 years without a break.”

Adman took Alexandra along for the ride when she turned 18. The hobo population ranges from professors to the truly homeless and everyone in between, she notes: “I even met a guy who was born on the road. He existed well into adulthood without a social security number just because that’s the life he was born into.” Or there’s Sack Kid, the tech genius whose company kept giving him sabbaticals because “all he wanted to do was be on the road riding freight trains, and all they wanted to do was keep his brilliance close.”

You might walk into a hobo jungle and end up in a philosophical discussion only to find out you’re talking to a philosophy professor who was drawn by the allure of trains. “You find people living their own dualities — people with big dreams,” Alexandra explains. “Until you understand that level of adventure and freedom and wanderlust they are living and seeking, I don’t know that you can truly understand who they are.”

Compelled by the hobo community from a young age, she would eventually fall into her own duality. “People would jungle up in Minneapolis along the river, so I’d go with my dad and have dumpster-dived pizza and old coffee grounds mixed in a pot of water,” she says. “The next day, I’d throw on a sweater, put my hair up so it didn’t smell like smoke and meet my mom for brunch.”

Adman’s motivation was to “get this world to understand that these hoboes lived, that they’re real humans and that they matter,” says Dori. “In that world, he was a great spokesperson, even down in Britt at the convention. He was able to translate what the hoboes were looking for and bring it to the city in a way that they could better understand. He was a bridge between them.”

At last summer’s convention, the deeply nostalgic and tradition-centric community mourned Adman’s passing with a tear-stricken funeral. In the hobo world, he had found what he was lacking in “polite society.” Before his death, he wrote that “riding freight trains doesn’t guarantee that one has found inner peace. It does, however offer the opportunity to free our minds from the committee of chaotic voices that scatter our inner peace.”

“Living in civilization’s rut, with our minds stuck on autopilot — routines followed rather than choices made — makes us a prisoner in the freest country on earth. But being on the road, living spontaneously and confronting a myriad of incidents every day, is living fully and creatively where one cannot count on routine to survive, having the audacity to live reckless and free in order to live a life in technicolor brilliance! Some of us are capable of totally shedding responsibility for a time to walk to the edge of a cliff and purposely choose to live.”

Hobo Royalty

Think the Miss America pageant but for hoboes: Each year, the community elects its royalty, choosing a king and queen to represent them. Competition is intense and involves extensive campaigning during the National Hobo Convention. Campaign signs speckle the walls of the hobo jungle, and candidates prove their loyalty by performing service for others and prove their reputation as authentic hoboes who have ridden freight trains.

In fact, when I meet current king Tuck, a hardened hobo with tattoos of locomotives and the confidence of a long-time train hopper, he doesn’t have time to speak with me — he has too much campaigning to do. It is a particularly important year for him, as he and his wife, Minneapolis Jewel, are vying to become the first ever married king and queen. A former Great Lakes merchant marine, she adopted the hobo way of life after reading an article on the subject in Penthouse magazine back in 1979. She has a tattoo that reads “Stay Hungry.” This is his second reign, her fifth. According to the couple, who lives in the Twin Cities, Minnesota is home to the most former hobo kings and queens of any state.

Read this article as it appears in the magazine.