Great art doesn’t stick with us as much as it becomes a second shadow that reveals its secrets when the light is just right.

For me, that shadow is The Great Gatsby. You remember — the book we had to read in high school, the one about star-crossed lovers, American exceptionalism and 1920s drinking habits? Gatsby started shadowing me in senior English class, where I fell hard for its poetry and moody melodrama. It followed me through my twenties and into my thirties, at which point I realized that it’s less a doomed romance than a cautionary tale about desire and hard choices and the fact that everyone, no matter where you stand, must look into the void at some point and take stock. In other words, it’s a story about adulthood.

I lost track of the book for a while, though I did see Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation, which is basically a two-hour music video starring Leonardo DiCaprio’s angry eyebrows. Then, one day in 2016, the shadow re-emerged. My family and I had just moved to the east side of White Bear Lake, and while we were settling into our new community, someone casually mentioned that F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, used to hang out at the White Bear Yacht Club and in the surrounding Dellwood area. Like many lifelong Minnesotans, I knew of the writer’s deep St. Paul roots, but I had never heard about his connection to the iconic lake and the club that’s still in business today situated less than two miles from my house.

Compelled by my inner fanboy and reporter’s spidey sense, I decided to dig deeper. In a dusty corner of the Internet, I came across a letter Fitzgerald sent editor Max Perkins from Dellwood in 1922. Scott and Zelda were near the peak of their fame at the time, drunken avatars of the Jazz Age who had danced naked in New York City water fountains and dined with the Churchills in London. But Fitz had yet to produce his greatest work. At the yacht club, he began outlining his third novel. In the letter to Perkins, he wrote that it would be set in “the middle west and New York of 1885 I think. It will concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually and will be centered on a small period of time. It will have a catholic element.”

That’s not exactly how The Great Gatsby turned out, but the skeleton is there. Minnesota versus New York. The short, not-so-sweet timeline. Less superlative beauties, like Myrtle Wilson, the novel’s doomed mistress.

Though well-known to Fitzgerald scholars, the letter made me wonder if, in obsessing over Gatsby’s Long Island parties and manic Manhattan energy, the experts had underestimated the influence of Dellwood and White Bear Lake. The book was set in the summer of 1922, after all. Are there other, less obvious connections? Is there a chance that this Great American Novel is, in some small way, a Minnesota lake novel? Am I a hubristic jerk to think I know better than the historians?

“You can’t repeat the past,” notes Gatsby narrator Nick Carraway in one of the novel’s most famous scenes. To which the eponymous billionaire responds, “Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!” Now, we all know that’s not true — just ask Gatsby himself, whose misguided optimism proves to be his fatal flaw — but surely you can rethink the past, right?

![]() Thomas Boyd arrived at the two-story Colonial in Dellwood sometime in the afternoon. The young literary critic and a friend had left work early that day, driven from the stuffy St. Paul Daily News offices by the late August heat. On a whim, they’d grabbed a bottle of gin and motored out to White Bear Lake, kicking up dust as they passed pumpkin fields and farmhouses along the county road.

Thomas Boyd arrived at the two-story Colonial in Dellwood sometime in the afternoon. The young literary critic and a friend had left work early that day, driven from the stuffy St. Paul Daily News offices by the late August heat. On a whim, they’d grabbed a bottle of gin and motored out to White Bear Lake, kicking up dust as they passed pumpkin fields and farmhouses along the county road.

When they reached Dellwood, they flagged down a laundry truck and asked the driver if he knew where they could find the famous writer who was renting a house in the area. He led them to a pretty summer cottage half a mile from the northeast corner of the lake. Boyd parked the car, grabbed the gin and walked up a brick pathway to the front door. “I’ll be down in a minute,” came a voice from inside.

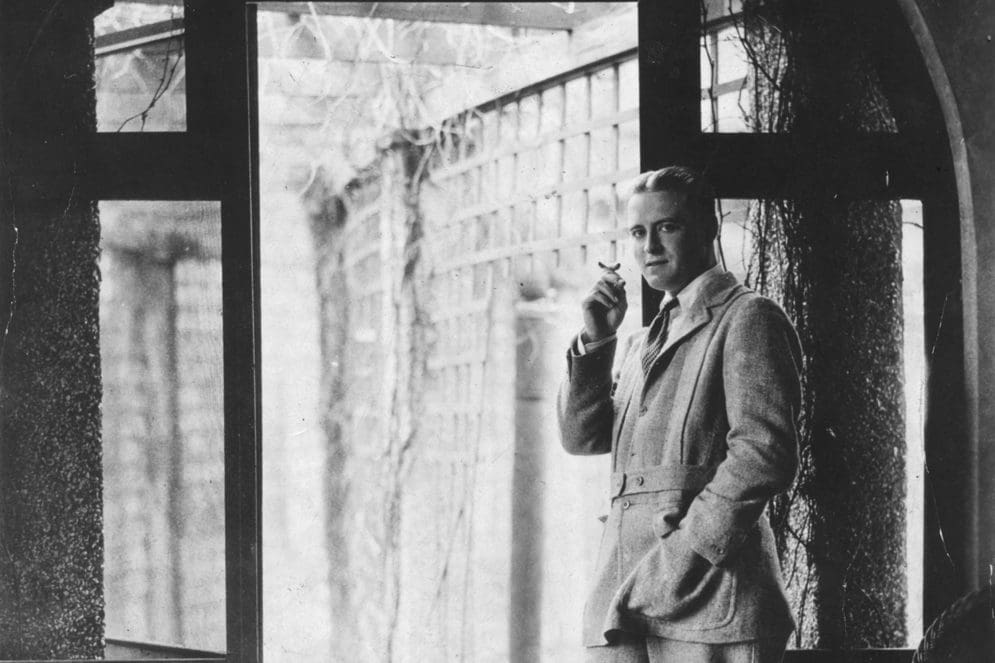

Boyd and his friend retired to the screen porch, and a moment later, there he was: F. Scott Fitzgerald, all of 24 at the time, dressed in robin’s egg blue pajamas and holding lemons and oranges to pair with the gin. Though Boyd had never met the author in person, Fitzgerald had sent him a letter earlier that year asking why the newspaper never reviewed his work. Boyd responded by becoming a super fan, and now here he was, face to face with the author in the summer of 1921.

“Why, I thought you’d be wearing a frock coat and a long white beard,” said Fitzgerald, teasing the 23-year-old book reviewer.

“And I thought you would be a baby with rouged lips,” Boyd shot back.

They spent the rest of the afternoon riffing on everything from poet Carl Sandburg to World War I. Fitzgerald remained uncharacteristically sober. Boyd got good and tanked, and those hot, boozy hours must have made an impression, because he would eventually write four different articles about that day. “Scott Fitzgerald is a youth that American literature will have to reckon with,” he predicted in the August 28, 1921, edition of the Daily News.

Nearly a century later, I walk up to that same Dellwood house and knock on the front door. The exterior looks nearly as it did in 1921, though the screen porch was swapped out years ago for a four-season addition. I half expect the ghost of Minnesota’s most famous literary son to answer, but instead I’m greeted by semi-famous Minnesota state Representative Matt Dean, whose family now lives here.

He invites me in and points out the area where Fitz and Boyd would have met. It’s a sitting room now, but the traditional furnishings make it easy to imagine that 1921 happy hour. I ask Dean how he feels about the home’s Fitzgerald connection, and he responds in the most Minnesotan way possible: “Kinda neat.”

It is kinda neat! Not only is that blue house off Highway 96 notable for being the site of the only extended interview Fitzgerald ever gave, but it’s one of the few tangible pieces of evidence we have from his often-overlooked White Bear period. After a quick stay in Zelda’s native Alabama, the nomadic couple moved north, spending August, September and part of October at the cottage. They returned to Dellwood a year later and rented an apartment at the White Bear Yacht Club for the better part of three months.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. To truly understand Fitzgerald’s time in Dellwood, you should know that White Bear is a lake of stories. It takes its name from a Dakota legend about a giant bear killed on Manitou, its only island. After white settlers drove out Native American inhabitants in the mid 1800s, the lake became a playground for upper-crust St. Paul residents who were drawn to its spring-fed waters and wooded lagoons. By the end of the century, resorts lined its western shores. Visitors arrived by train, among them Mark Twain, who wrote the following appreciation in his 1883 memoir Life on the Mississippi: “It is a lovely sheet of water. … There are a dozen minor summer resorts around about St. Paul and Minneapolis, but the White-bear Lake [sic] is the resort.”

Other narratives aren’t nearly as flattering. In the 1930s, the lake was a hideout for Ma Barker and other gangsters. And later came the horrifying murder of three-year-old White Bear resident Dennis Jurgens by his adoptive mother, a case that made national headlines when she was prosecuted in the late 1980s.

These stories and others sit on the bookshelves of the White Bear Lake Area Historical Society library. Or, more specifically, in a small research room that smells like cigarettes and musty attic. If you ask nicely, a staff member will help you find a large bound book filled with original copies of the area’s long-running weekly rag, the White Bear Press.

Paging through yellowed 1922 editions of the paper one afternoon, I find a short item that reads, “Mr. and Mrs. F. Scott Fitzgerald, of St. Paul, moved to the White Bear Yacht Club this week, where they will remain during the summer months.”

The news ran on June 1, 1922, in the publication’s Ripples Around the Lake section, an exceedingly polite gossip column that tracked the comings and goings of notable residents. For all the shenanigans the couple was rumored to have partaken in that summer, I’m surprised the four-line blurb is the only mention I can find of them.

Before leaving the library, I ask the woman working that day why Fitzgerald still matters. “It’s the sentences,” she says. “In just a few words, he can bring you right there. He lulls you into this perfect place.”

![]() In desperate need of more ripples around the lake, I turn to Dave Page, historian and author of multiple books about the writer’s time in the Twin Cities. His latest is coffee-table tome F. Scott Fitzgerald in Minnesota, a glossy tour of sites that doubles as a biography. I skip past the St. Paul trivia (born there in 1896, returned with his family in 1908) and head straight for the chapter about White Bear.

In desperate need of more ripples around the lake, I turn to Dave Page, historian and author of multiple books about the writer’s time in the Twin Cities. His latest is coffee-table tome F. Scott Fitzgerald in Minnesota, a glossy tour of sites that doubles as a biography. I skip past the St. Paul trivia (born there in 1896, returned with his family in 1908) and head straight for the chapter about White Bear.

Page, bless the man, has done his homework. Fitzgerald’s White Bear story starts in his teenage years. Though his family always had money (they lived in a string of cushy Summit Avenue row houses), he ran with the über-rich — a lifelong habit that he wrestles with in all of his best work. And back in the 1910s, St. Paul’s über-rich summered at White Bear. Privatization of the lake was in full effect. The public still flocked to the amusement park in Mahtomedi, but many of the resorts had burned down and in their place stood enormous lake retreats.

A teenage Fitzgerald spent time in some of these homes, including the Manitou Island cottage of hardware wholesaler Charles H. Bigelow, grandfather of Fitzgerald’s friend Alida. He also visited his friend (and crush) Elizabeth Clarkson at her parents’ chalet-style getaway in the exclusive new Dellwood settlement. In September of 1913, the Clarksons invited him out to the lake for dinner. Afterward, they all went down to the White Bear Yacht Club and watched a staging of Coward, a play the 17-year-old Fitzgerald had penned as a member of St. Paul’s Elizabethan Drama Club.

That fall, Fitzgerald went off to Princeton, and, as far as I can tell, didn’t return to Dellwood until he and Zelda rented the two-story Colonial in 1921. The years between visits were dizzying for Fitzgerald. He graduated from college, joined the Army, met and dated a Southern belle who eventually dumped him because he didn’t have any money, and published a well-received debut novel, This Side of Paradise, that gave him some money and ultimately convinced the Southern belle to marry him. Cue the Champagne pop and big-band soundtrack.

The author must have felt like a king returning to Dellwood. He had written the book and gotten the girl. And unlike his teenage visits, he was no longer someone’s plus-one in this land of summer privilege.

Though Fitzgerald polished his next novel, The Beautiful and Damned, and wrote a couple short stories, he mostly drank. And drank. Writes Page in his book: “After one particularly boozy night, Scott forgot to veer right in his shared drive and ended up in the neighbors’ flower garden. Mr. Donahower awakened to discover an open-topped Pierce Arrow blocking his way, its famous driver fast asleep at the wheel.”

The other juicy Fitzgerald story from the summer of ’21 is likely fictional. According to local lore, the cottage’s owner, Mackey Thompson, asked Scott and Zelda to leave in October after they caused a plumbing accident. Some say it was a burst pipe, though it could have been an overflowing sink or tub. When I visit the house, Matt Dean directs me to a flight of stairs leading up to the second floor. They’re warped, which he says could be proof of an incident that started in the bathroom at the top of the steps. In reality, the couple probably left on their own accord so the pregnant Zelda could give birth to daughter Scottie, their only child, in St. Paul.

When the Fitzgeralds moved into the yacht club the following summer, they brought a nurse to look after the baby, which freed them up to swim and golf with friends like Charles Oscar Kalman and Alexandra Robertson, who had a summer place in Dellwood. The couple was also tight with Lucius Pond Ordway, one of the original partners in 3M, and his wife, Jessie.

Stories swirl around that summer like wind off the lake: Sinclair Lewis drank the couple under the table one night. Scott performed a Scottish sword dance with his putter on a golf green. Zelda passed out during dinner and had to be carried back to their apartment. These could all be myths, but somebody smarter than me once said that a myth is actually a poetic telling of a basic truth.

Speaking of truth, thanks to that letter Fitz sent Perkins, we know with some certainty that the author started to think about his third novel in the summer of 1922. I call Page to needle him about deeper White Bear–Gatsby correlations. “Something at Dellwood inspired Fitzgerald to do an Edith Wharton–like New York novel,” he tells me. “But what it is, I don’t know.” He mentions Mary Jane LaVigne, another Fitzgerald scholar and supposed expert on the Dellwood period, but he says she probably won’t talk.

And he’s right. LaVigne is almost comically guarded when I get her on the phone. She won’t even let me record the call. But I get it; historians can be territorial with their findings. And if she’s got a Fitzgerald scoop, why would she share it with an outsider like myself? I start to worry that my quest to find Gatsby at the lake is as foolish as his plan to win back Daisy Buchanan after all those years.

![]() In So We Read On, Maureen Corrigan’s excellent deep dive of Gatsby, she writes, “Gatsby’s magic emanates not only from its powerhouse poetic style — in which ordinary American language becomes unearthly — but from the authority with which it nails who we want to be as Americans. Not who we are; who we want to be. It’s that wanting that runs through every page of Gatsby, making it our Greatest American Novel.”

In So We Read On, Maureen Corrigan’s excellent deep dive of Gatsby, she writes, “Gatsby’s magic emanates not only from its powerhouse poetic style — in which ordinary American language becomes unearthly — but from the authority with which it nails who we want to be as Americans. Not who we are; who we want to be. It’s that wanting that runs through every page of Gatsby, making it our Greatest American Novel.”

Well, Maureen, I’ve got a serious case of the wantings. Maybe what I want is some ownership over Fitzgerald. Isn’t that what we always do with our heroes: project our hopes and fears onto their work in a borderline possessive way?

My favorite scene in The Great Gatsby takes place at Tom Buchanan’s secret love shack in Manhattan. In chapter two, he and mistress Myrtle Wilson throw an impromptu party at the apartment, and at one point narrator Carraway gives his drunken take on the scene: “High over the city our line of yellow windows must have contributed their share of human secrecy to the casual watcher in the darkening streets, and I was him too, looking up and wondering. I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

Like so many Fitzgerald passages, this one is a layer cake. On its surface, it’s drunken poetry. Who hasn’t had one cocktail too many and marveled at the overwhelming beauty of it all? But Fitzgerald is also tipping his hand, reminding us of his lifelong struggle to fit in while also wanting to check out.

This insider-outsider dance hits home. I live in a relatively modest stucco home on the non-lake side of Mahtomedi, and I’d be lying if I told you I wasn’t a little jealous of the residents of the much larger, much nicer houses that sit along the water. At the same time, I’m a big proponent of the old “money doesn’t buy happiness” adage — though that’s easy to say when you live someplace where nearly everyone is well-off. (First-world problems, right? Sigh.)

Unsure where to turn next, I go back to my notes, looking for clues, a sign, anything. Everyone I’ve talked to thus far shares a love of Fitzgerald’s writing at the line level, from the woman at that White Bear library to Robert Steven Williams, a filmmaker who argues that Westport, Connecticut, also deserves some credit for inspiring Gatsby. (Scott and Zelda spent the summer of 1920 there; Williams claims to have proof that they stayed in a small house next to a towering mansion owned by a mysterious billionaire.)

Maybe the clues have been on the page this whole time. I comb Gatsby once more for any direct references to Dellwood or White Bear. Is the robin’s egg blue uniform worn by Gatsby’s chauffeur a nod to the pajamas Fitzgerald donned when he met Boyd, the book reviewer? What about in chapter six, when Carraway gets oddly specific about the date — July 5, 1922? Fitzgerald would have been at White Bear at the time, but only history knows if anything important happened beyond, perhaps, a post–Fourth of July hangover.

I turn to other texts. Somehow I’d missed a short story called “Winter Dreams,” written just before Fitzgerald left White Bear in September of 1922, and years later described by the author as “a sort of first draft of the Gatsby idea.” The story contains obvious nods to White Bear and Gatsby. It takes place on Black Bear Lake. It concerns a proto–Don Draper who chases the idea of perfection as embodied by an unattainable beauty.

Fitzgerald scholars know “Winter Dreams” well, yet they tend to get bogged down by the story’s thematic similarities to Gatsby. But if we accept that the story is a first take on his masterpiece and at the same time clearly based on his White Bear Lake period, then shouldn’t we also compare nonfictional 1922 Dellwood to fictional 1922 Long Island?

Look who Dellwood attracted back then: Old money. New money. Artists. Touring vaudeville performers. It’s just the kind of sociocultural jumble you’d expect at one of Gatsby’s epic pool parties. In a book about the history of White Bear Lake’s east side, historian Paul Clifford Larson describes a fledgling Dellwood as having a pronounced East Coast vibe, noting that an early iteration of the White Bear Yacht Club looked like an Adirondack lodge. He also writes that Dellwood made yachting culture the center of residents’ social and recreational lives, similar to “many resort settlements on the Atlantic seaboard.” Larson doesn’t state it outright, but Dellwood circa 1922 sure sounds a lot like Long Island on the lake.

Finally, look at the geography. White Bear Lake has two distinct features that have been occupied by the affluent for more than a century and are given prominent placement in “Winter Dreams”: Manitou Island to the west and the peninsula to the east. Looking at a map of the lake, it’s not a stretch to think that these landmasses could be rough precursors of East Egg and West Egg, the fictional Long Island communities in Gatsby.

OK, so “Winter Dreams” isn’t quite the smoking gun I was looking for. It doesn’t prove that Fitzgerald’s 1922 Dellwood stay is the most important summer vacation in literary history. But it’s something better. It’s the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. It’s hope. It’s something to build on. (Your move, historians!)

Near the end of winter, I drive onto Manitou Island. Technically, I’m trespassing; it’s a gated community with signs warning the plebes to stay out. But I press on in my crappy minivan, past old estates and new McMansions. Near the south end of the island, I look out across the water. The lake is still frozen, though the top layer of snow has nearly melted. About three-quarters of a mile off sits the peninsula. There are no docks out yet, of course, just beautiful home after beautiful home. One of them is the old Read cottage, where Fitzgerald sometimes stayed as a teenager. Apparently he liked to sit on the big, airy front porch and daydream. If you squint from my vantage, you can picture him there, a young man with so many stories ahead of him.

Tour de Fitz

Minnesota’s greatest F. Scott Fitzgerald hits — plus a couple B-sides for the nerds.

481 Laurel Avenue, St. Paul

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (what a name) was born on September 24, 1896, at his parents’ apartment. And, yes, he was named after the national-anthem lyricist, who happened to be a distant relative on his father’s side. This three-story structure is on the National Register of Historic Places and has been designated a Literary Landmark.

294 Laurel Avenue / 499, 509 and 514 Holly Avenue, St. Paul

It’s easy to see where the writer got his wandering streak. Between 1908 and 1913, his family bounced around to various row houses in the Summit Hill area.

94 Dellwood Avenue, Dellwood

As a teen, Fitzgerald visited friend Elizabeth Clarkson, who summered with her family at this Alpine-style lake home.

56 Dellwood Avenue, Dellwood (White Bear Yacht Club)

When he wasn’t hanging out at private lake homes, a young Fitz swam, sailed and played tennis at the White Bear Yacht Club. Years later in the summer of 1922, he and wife Zelda moved into an apartment here and partied hard; some say they were kicked out for bad behavior. Sadly, that building burned down in 1937, though an American Colonial–style clubhouse was quickly built to replace it.

2279 Marshall Avenue, St. Paul (Town & Country Club)

While home on break from Princeton in 1915, the writer and his friends threw a party at the swanky Town & Country club. Chicago socialite Ginevra King was in attendance, and Fitz fell hard for her. Though she broke his heart, she would later inspire some of his most memorable female characters, including Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.

599 Summit Avenue, St. Paul

Fitzgerald’s parents lived in this three-story apartment building, known for its grand tower, from 1918 to 1919. After college and a stint in the Army, he moved in with them and completed his debut novel, This Side of Paradise. The apartment survives today thanks to its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

374 Selby Avenue, St. Paul (W.A. Frost)

Before it was a restaurant with one of the best patios in town, W.A. Frost was a pharmacy. Fitz often stopped here with friends.

14 Dellwood road, Dellwood

Scott and Zelda rented this summer cottage in August 1921. Instead of writing, he mostly drank, and one night he crashed his car in his neighbor’s flower bed. Legend has it that their landlord evicted the couple that October after they caused a plumbing accident.

79 Western Avenue, St. Paul (Commodore Hotel)

Just before the birth of their daughter, Scott and Zelda decamped for the fancy Commodore Hotel. Today, the building houses a celebrated bar and restaurant, making it one of the few Fitzgerald sites open to the public.

626 Goodrich Avenue, St. Paul

When baby Scottie entered the scene, her parents decided a jazz hotel with a speakeasy in the basement wasn’t the best place to raise a child. So they rented part of this large Victorian home that was owned by a friend’s relatives.

420 Summit Avenue, St. Paul (University Club)

Yet another favorite haunt during Scott and Zelda’s St. Paul heyday, this 105-year-old club still stands today. Did the author really carve his initials into the bar here? That’s members-only information, old sport.