All products featured on ArtfulLiving.com are independently selected by our editors. We may earn commission on items you choose to buy.

Fly-fishing, like many worthy pursuits, requires a learning curve. That learning curve feels quite steep at times. You may find your line caught in trees, your fingers struggling to tie knots, or your rod — the rare object that is both strong and fragile — snapped in two (though I’ve also broken them, by a miracle of physics, into three). That’s all before the fish get involved, and they rarely cooperate.

But when everything aligns (and even when it doesn’t), fly-fishing is a delightful diversion. For some of us, it has become the main attraction.

The sport really began with trout in the English chalk streams. They live in cold water in very appealing places worldwide, like Patagonia’s great rivers, Montana spring creeks and winding brooks in Wisconsin’s Driftless area. So you’re already in a beautiful setting and, ideally, out of reception. You’ve escaped the forced urgency of emails, the social media hum and all those notifications about developing stories. (I’m prepared to wait until the story is fully developed.) Yes, you’re on the water and out of time.

Now, all you have to do is catch a fish. If you want to do this the easy way, you wouldn’t pick up a fly rod. But that’s alright. We’re aiming for something higher here, a certain ideal, an artfulness, though we rarely meet that lofty standard. We move the rod back and forth — the cast is harder than it should be — but if everything goes well, the line gently unfurls and the fly lands on the water and drifts down the current toward a willing trout.

In this moment, the sport is no longer about aesthetics and overwrought poetry. When that fly moves over the fish, we enter the realm of action. Or potential action, anyway. This drift is important. The fly must move in the current naturally; if there’s any drag, no discerning trout will bother. And trout are nothing if not discerning. You might drift a fly over a trout and be rejected, often more than once. This can be frustrating. What more do they want? we ask. Sometimes the fish will come right up — you can see them clearly in the river — and turn away. I’ve seen trout open their mouths and decide at the last possible second, No, this isn’t for me, while my knees went weak.

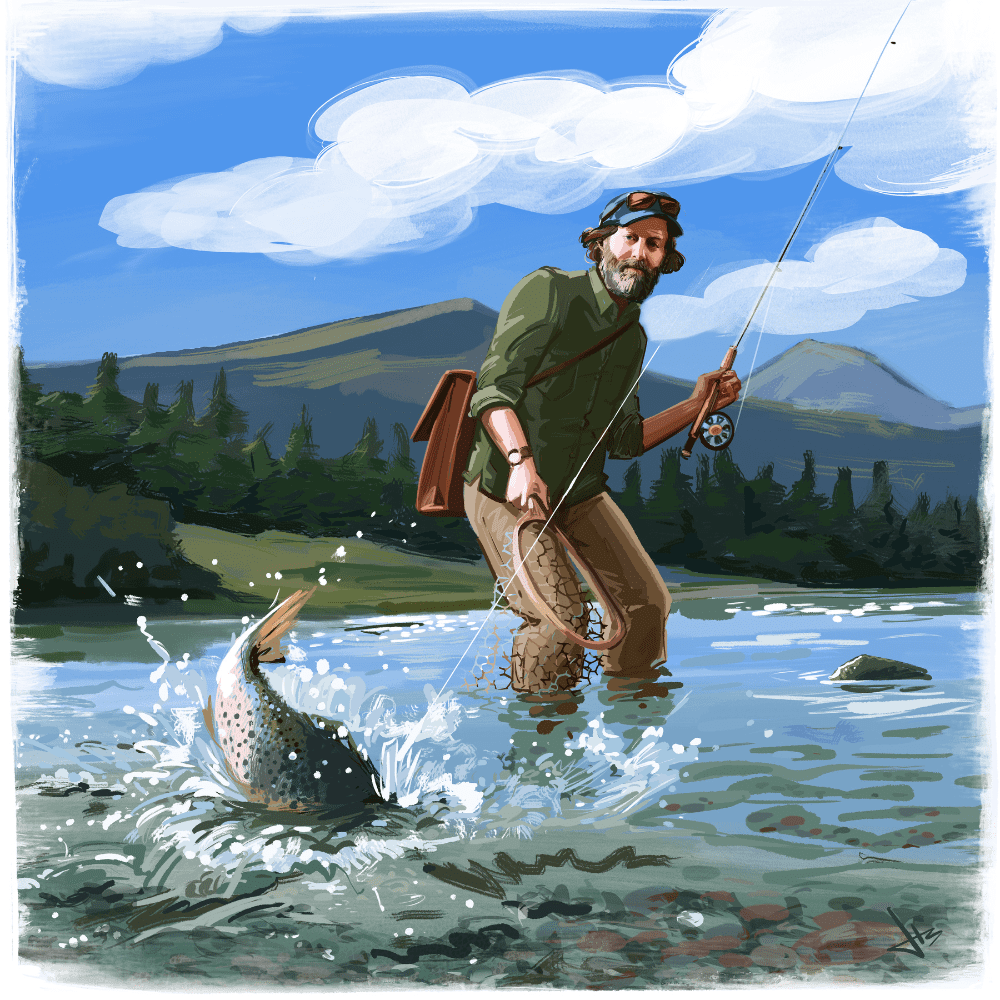

But every so often, the fly disappears in a little splash, sometimes so subtly you barely notice. Don’t be deceived, though: Those subtle takes can be caused by large trout. You raise the rod to set the hook. There’s a brief second, which seems to last for an eternity, before the line goes tight. Until that happens, you’re suspended, uncertain if you’ve connected to the fish. Today, the angling gods have smiled upon you, and you feel the weight of the fish. Game on.

Fly-fishing uses light tackle — you can’t simply reel the fish in, as the line is so fine the fly will break off. (I told you this wasn’t the easiest way!) You try to keep pressure on a trout that wants no part of you. It may swim upstream away from you; it may jump out of the water. The first time you see any trout is always exciting. Now you know what you’re dealing with.

This connection, this fight is the burst of action that gives fly-fishing its symmetry. Though it’s really asymmetry, since you’re not catching fish that often. This is the moment that you dream of, that justifies all the waiting and speculating. You’re part of a drama — and sometimes, it must be said, that drama turns into tragedy. I’ve lost fish in many ways, none of them satisfying. Sometimes the loss really is nobody’s fault, mere vagaries and the angling gods’ whims. Occasionally, the loss is due to what might be dubbed “user error.” Creaky reflexes, too much pressure — the list goes on. (To spare his feelings, we won’t name the user who has made this error.)

When it all works out, though, you net a brown trout — a fine creature. Not brown at all, really, but a gold flank with fine black spots, occasionally lined with vivid red. Finally, the circle is complete. Fly-fishing offers, in these rare moments, a deeper connection to the natural world and an escape from the fast-paced one where we spend most of our lives. Our skills improve over the years, though never as much as we hope. And the humbling moments make the successes all the more exhilarating. Yes, you can philosophize too much about fishing, and I certainly do. But then you move beyond that, gather yourself and make one more cast.

A Minnesotan turned New Yorker, David Coggins is the author of the New York Times bestseller Men and Style and writes a column for Artful Living. His latest book, The Believer: A Year in the Fly Fishing Life, comes out in April.