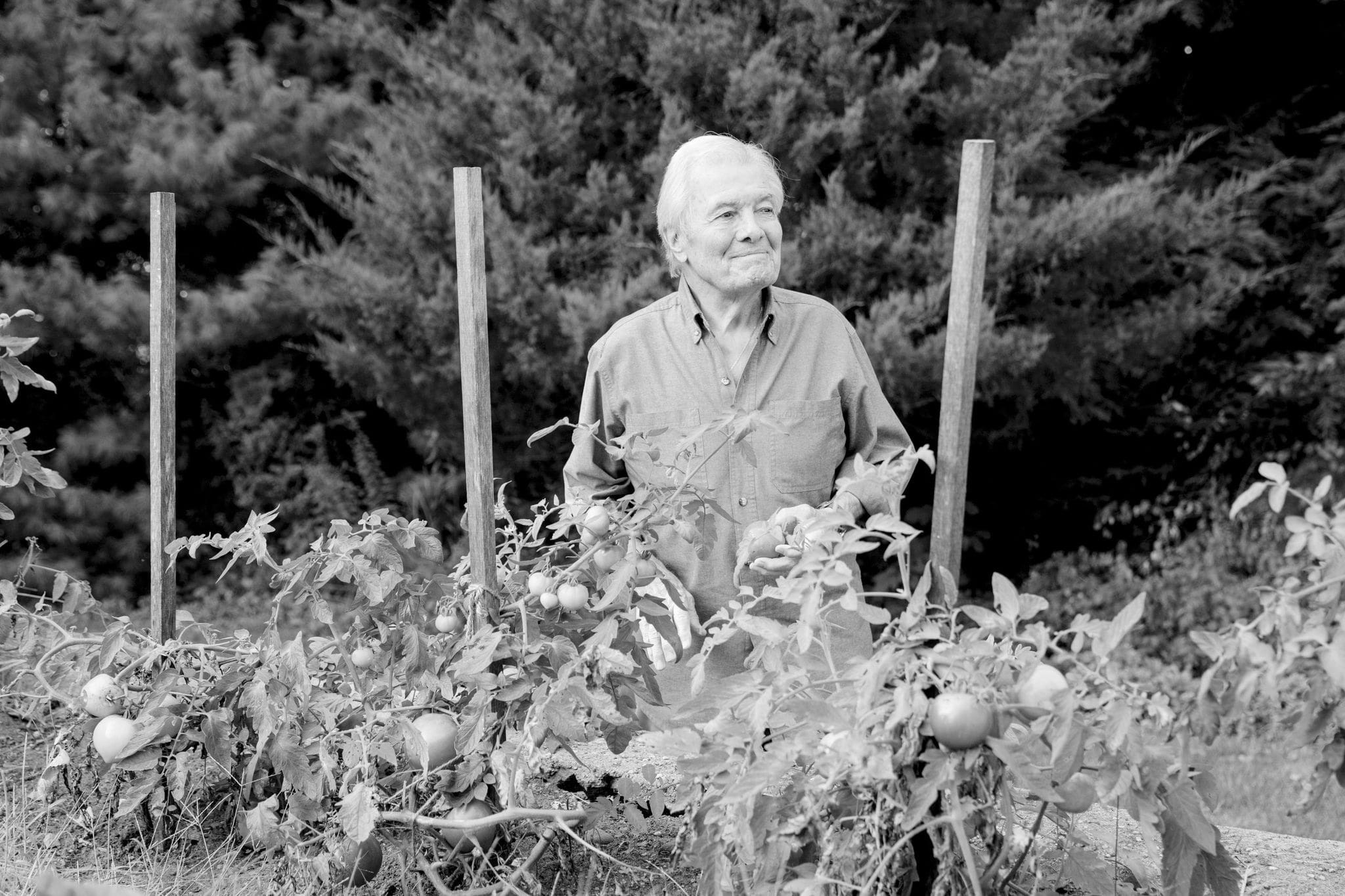

It’s as if the term bon vivant was created just for Jacques Pépin. The celebrated chef sat down for a very personal interview with us from his Connecticut home, where the ever-charming author and TV personality seems at ease these days, distilling life to the essential. “A perfect day for me is if my garden is blooming and I have friends over to play boules,” he says. “We drink wine together and cook together. That’s a really good day.”

Photography by Ken Faught

Surrounded by gleaming pots and pans and dozens of spoons and spatulas, the French-born chef tells us he’s busier than ever. At 87, he’s become a social media sensation thanks to his breezy cooking tutorials filmed inside his delightfully lived-in kitchen. With his casual plaid shirts and easy manner, he prepares whatever he’s in the mood for, signing off with his trademark “Happy cooking.” No surprise that his 1.6 million Facebook followers are obsessed. “The idea was my daughter, Claudine’s,” Pépin explains. “We use a fixed camera and a handheld phone over my shoulder. Usually we film 10 in a day, and it varies based on what I have left in the refrigerator or pantry.” Even more impressive, all the videos are improvised.

But what his newfound devotees might not know is that Pépin doesn’t just love cooking; he also loves painting. For decades, he’s been working diligently in his studio, capturing landscapes, florals, even vegetables. He got the bug in the 1960s as a student at Columbia University and has been creating art ever since.

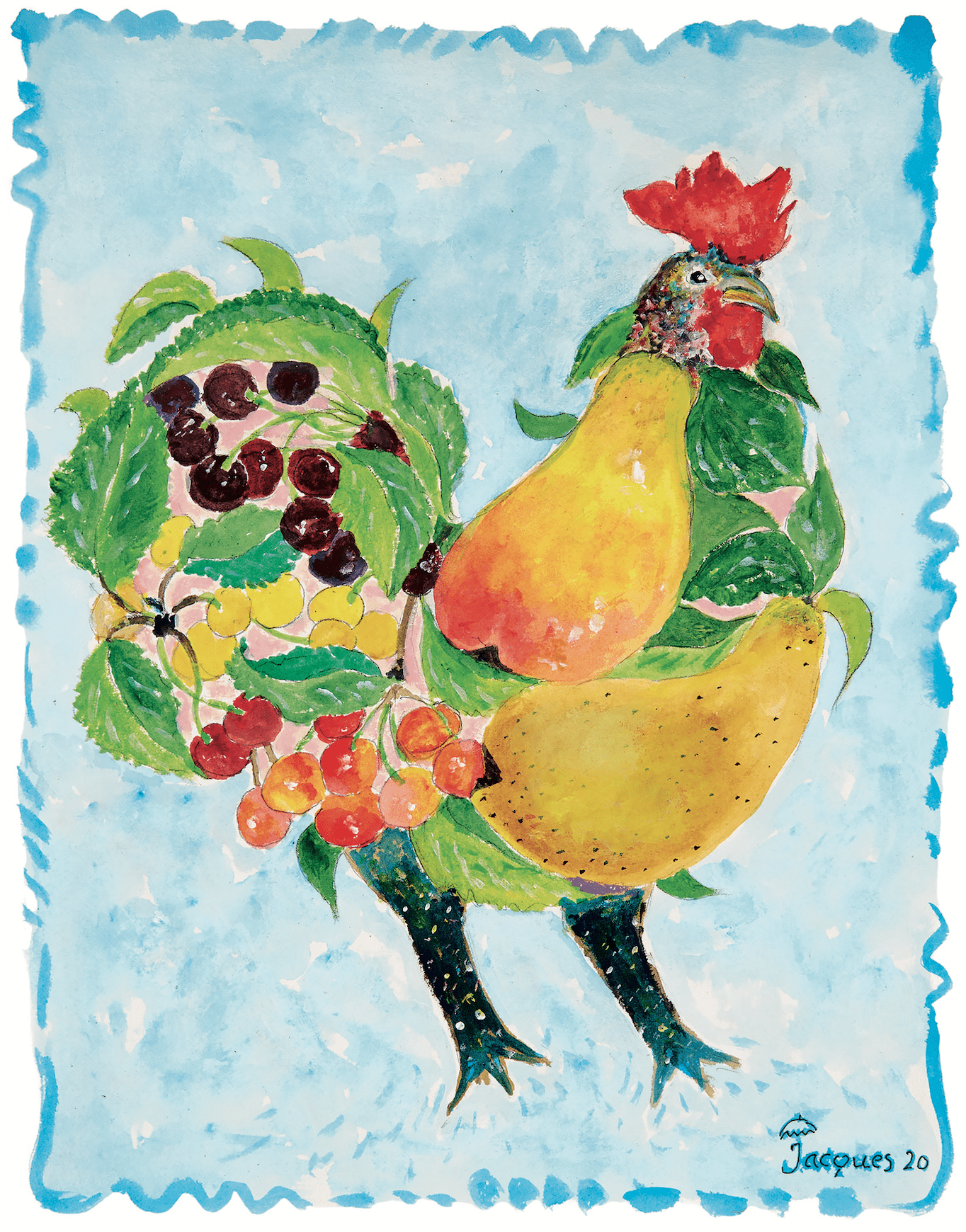

“Cherry Pear Chix” by Jacques Pépin from Art of the Chicken published by Harvest Books (2022)

“When I cook in the kitchen, there is a certain freedom of being a professional chef,” he extols. “You taste, you adjust; you taste, you adjust. And then the food kind of takes ahold of you. Similarly, when I start a painting, very often I don’t really know where I’m going. Then at some point, the painting takes ahold of me. And I react to it, without even trying to validate what I’m doing.”

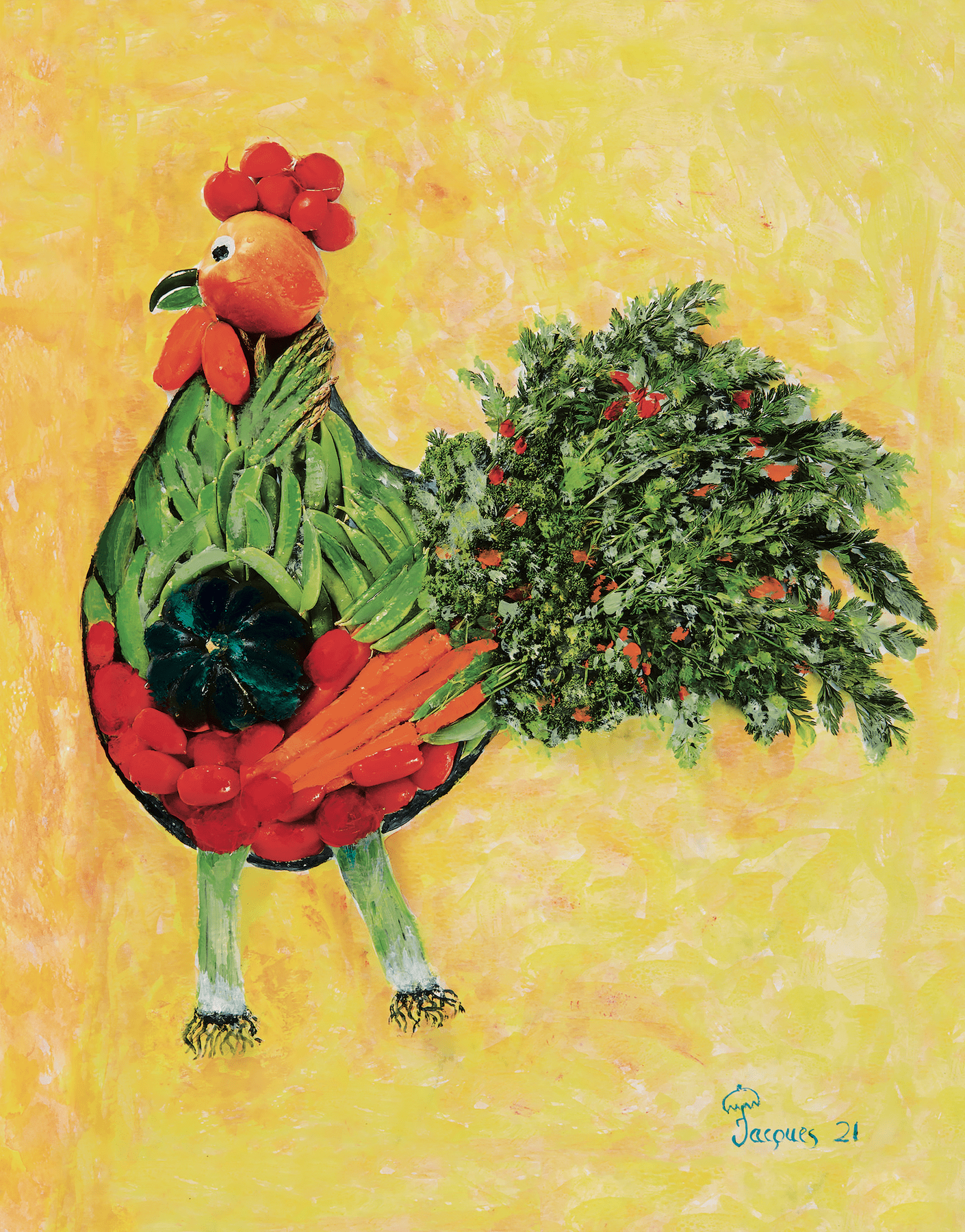

The subject matter he’s painted the most might come as a surprise: chickens. His latest book, Art of the Chicken: A Master Chef’s Paintings, Stories, and Recipes of the Humble Bird, is filled with dozens of his poultry portraits, each with its own personality. “I come from a place in France where we are known for our very special Bresse chickens,” Pépin says. “With their red comb, blue feet and white plumage, they’ve always been a part of my life.”

Photography provided by Jacques Pépin

Astonishingly, this is his 31st book — and perhaps his most personal. A visual and culinary treat, it is filled with stories of omelets and roasted birds. But you won’t find formal recipes here. Instead, Pépin explains how to cook in a narrative style, as if we were sitting right in his kitchen. Along the way, he folds in stories about his life and adventures in the culinary world.

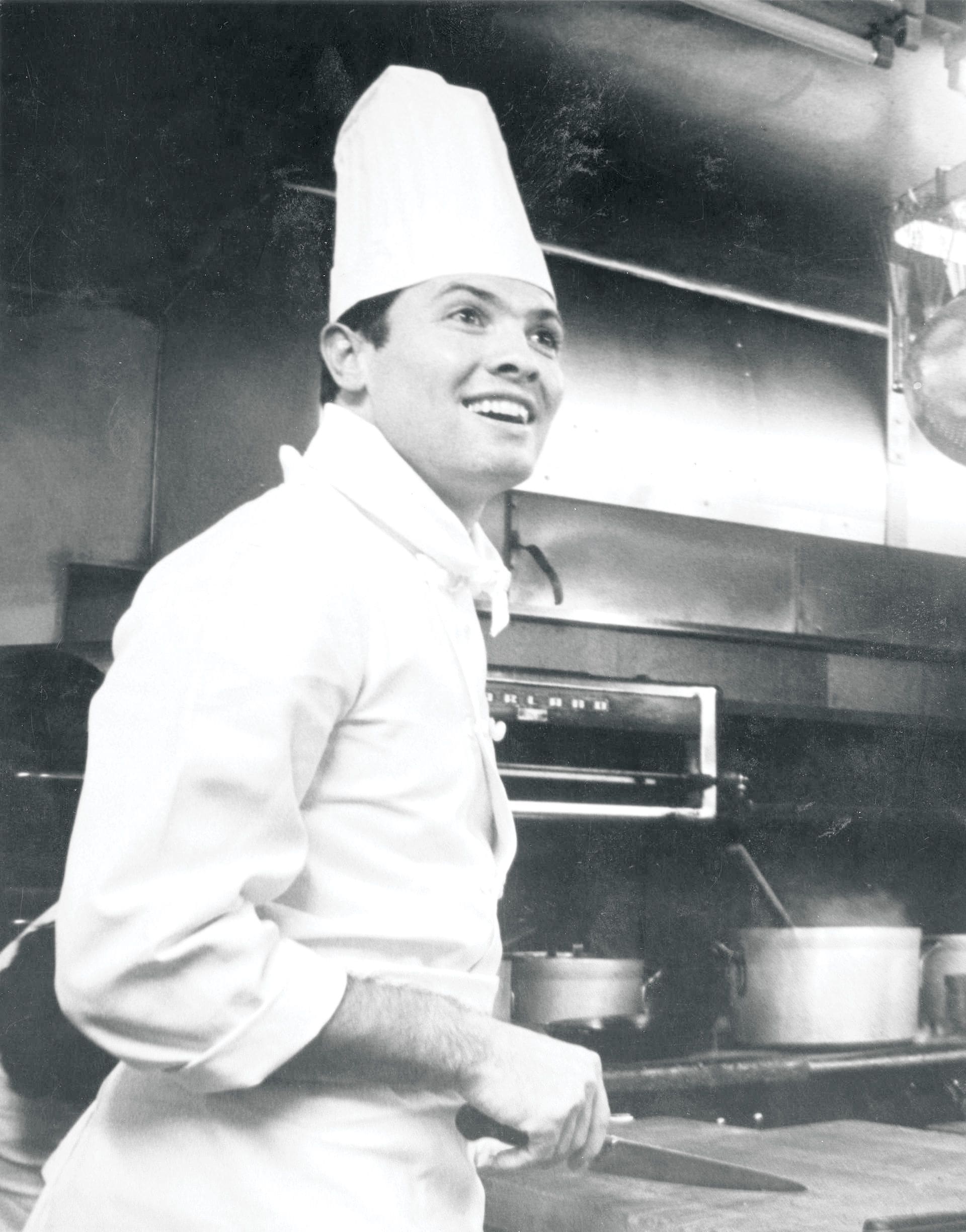

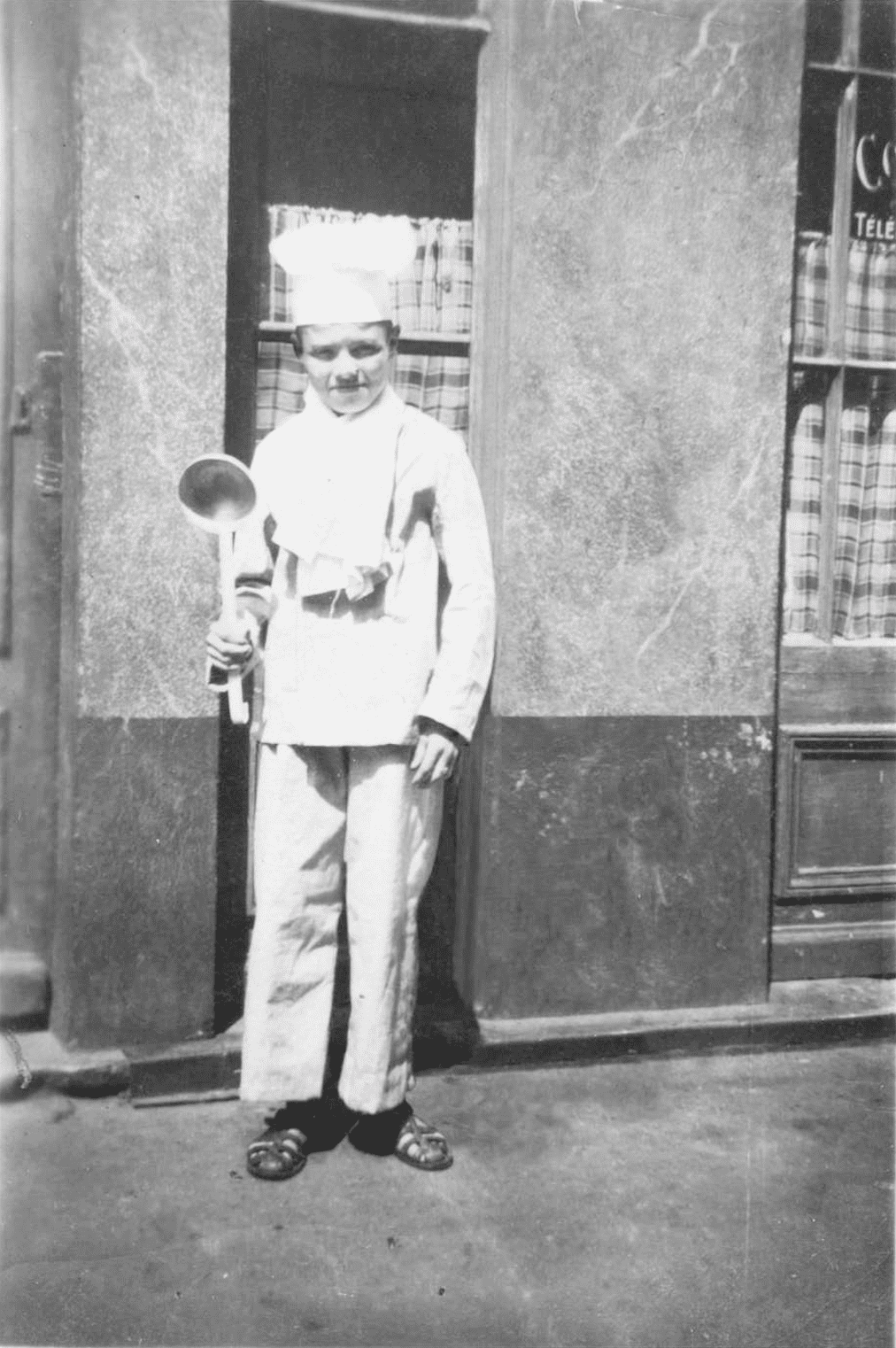

And what a life it’s been. Born in 1935 in Bourg-en-Bresse, France, he left home at 13 to become a chef. After rigorous stints in kitchens near Lyon then Paris, he spent time in the French military, where he cooked for President Charles de Gaulle. But after he came to America in 1959 and started working at New York City’s Le Pavillon, he turned down the chance to cook at the White House for President John F. Kennedy.

“Chix and Vege” by Jacques Pépin from Art of the Chicken published by Harvest Books (2022)

Instead, he pivoted and went to work for Howard Johnson’s, where he perfected the art of making chicken pot pies for the masses. “The years I spent at Howard Johnson’s changed my life as a cook,” Pépin writes in Art of the Chicken. “Learning about production, the chemistry of food, marketing and recipe writing all made me grow and helped me develop skills outside of cooking.”

But then in 1974, everything changed. While driving, he hit a deer and was so severely injured he nearly died. He broke his back, and his shoulder was so badly hurt that he could no longer work in a demanding professional kitchen. So he pivoted again and began giving cooking demonstrations at culinary shops across the country, along with lecturing at Boston University. Then in 1982, he found his way to TV, where his elegant cooking style made him a PBS star.

Photography provided by Jacques Pépin

TV fate knocked again in 1999, when he teamed up with longtime friend Julia Child for their show, Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home. They were a spirited pair, she with her quirky sense of humor and he with his poised wit. “We loved to argue because our verbal jousting for the most part concerned trivial matters,” Pépin writes. “Julia, for example, swore by regular salt and white pepper. I prefer kosher salt and black pepper and occasionally tried to sneak these non-Julia-approved ingredients into our demonstrations.”

Child and Pépin were among the first celebrity chefs in America, using TV to demystify French cooking. And while his notoriety has only grown over the years, he carries that fame with a heaping dose of humility. “Seventy years ago, the cook was at the bottom of the social scale; now we are geniuses,” he tells us. “I’m not sure how that happened — it can be dangerous.”

Photography provided by Jacques Pépin

To be sure, Instagram is filled with young chefs touting their latest masterpieces. But Pépin remains a firm believer in disciplined training. His early education in Paris was one of conformity, studying with one chef then another. He trained under Lucien Diat at Plaza Athénée, along with stints at Fouquet’s and Maxim’s. “Only then, after eight or 10 years like this, after you’ve absorbed multiple points of view, can you begin to filter it,” Pépin instructs. “Then you can bring your own sense of taste, your own aesthetic.”

Over the years, he has developed a more international style of cooking, blending recipes and ingredients from many cultural traditions. But his philosophy remains the same: Cooking together should be fun, recipes should be fairly simple, and taste should always trump presentation. “When you are a young chef, you have to put more on the plate — more garnish, and more and more,” Pépin explains. “Now in my eighties, if I have a good tomato out of the garden with a bit of salt and some olive oil, I don’t need many embellishments. So I retrieve, retrieve and take away from the plate, to be left with something more essential.”

Photography provided by Jacques Pépin

On this day, we ask Pépin about the home cook and what sage advice he has for those learning to cook. “Drink enough wine,” he quips. “People say, ‘I don’t cook at all.’ Well, if you have a friend who cooks, the next time you go see them, ask if you can come an hour early and cook with them in the kitchen. Bring a bottle of wine, drink the bottle of wine and if the chicken is over-cooked, who cares?”

He’s just as spirited talking about popular cooking TV shows, which are often filled with drama. “I know this is TV, but if cameras came into the kitchen of chef Thomas Keller, it’d be like a ballet back and forth with almost no noise,” Pépin points out. “But for TV, they want to create kitchens where people are yelling at each other and insulting each other. It doesn’t work like that in a professional kitchen, frankly. You don’t really teach people to cook by yelling at them.”

Photography provided by Jacques Pépin

These days, the master chef relishes the quiet of his Connecticut home, where he’s lived for 46 years. Everywhere, you’ll find photos of loved ones. After 54 years of marriage, his beloved wife, Gloria, passed away in late 2020. The sadness is palpable still. But his vivacious daughter, Claudine, and her husband, Rollie (also a chef), are always there in the background cheering him on. So too is his granddaughter, Shorey, who is in college now after growing up alongside Pépin in the kitchen.

In 2016, Claudine and Rollie helped set up the Jacques Pépin Foundation, which provides free culinary training through community-based organizations to individuals often excluded from the workforce due to issues like homelessness or previous incarceration. For fans of the beloved chef, there are also paid memberships granting access to a video recipe book as well as an exclusive Rouxbe course, “A Legacy of Technique.” The foundation has become a passion project for the entire family.

“Apple and Chicken” by Jacques Pépin from Art of the Chicken published by Harvest Books (2022)

And yet for this esteemed chef, his day-to-day life comes down to two things: food and art. “Cooking and painting complete me; both are the expression of who I am, and they connect in my life,” Pépin confides in Art of the Chicken. He elaborated on this notion during our conversation, telling us what he decides to paint often comes down to the specific day: “A lot of it depends on your mood. If it’s summer or winter; if it’s hot or cold. You’re in a good mood or a bad mood. There are moments in cooking where you follow your whim, and painting is the same way.”

More and more, Pépin is drawn to creating abstract works — a complex matrix of shapes and patterns, where plates of food and glasses of wine often work their way into the compositions. “The abstract paintings are the hardest ones to stop; you can go on and on,” he says. “It’s the same with food. If you work on it too much, the whole thing disappears. Just like painting — too long and all of a sudden you’ve destroyed it. I always say a painting is never finished, just abandoned.”

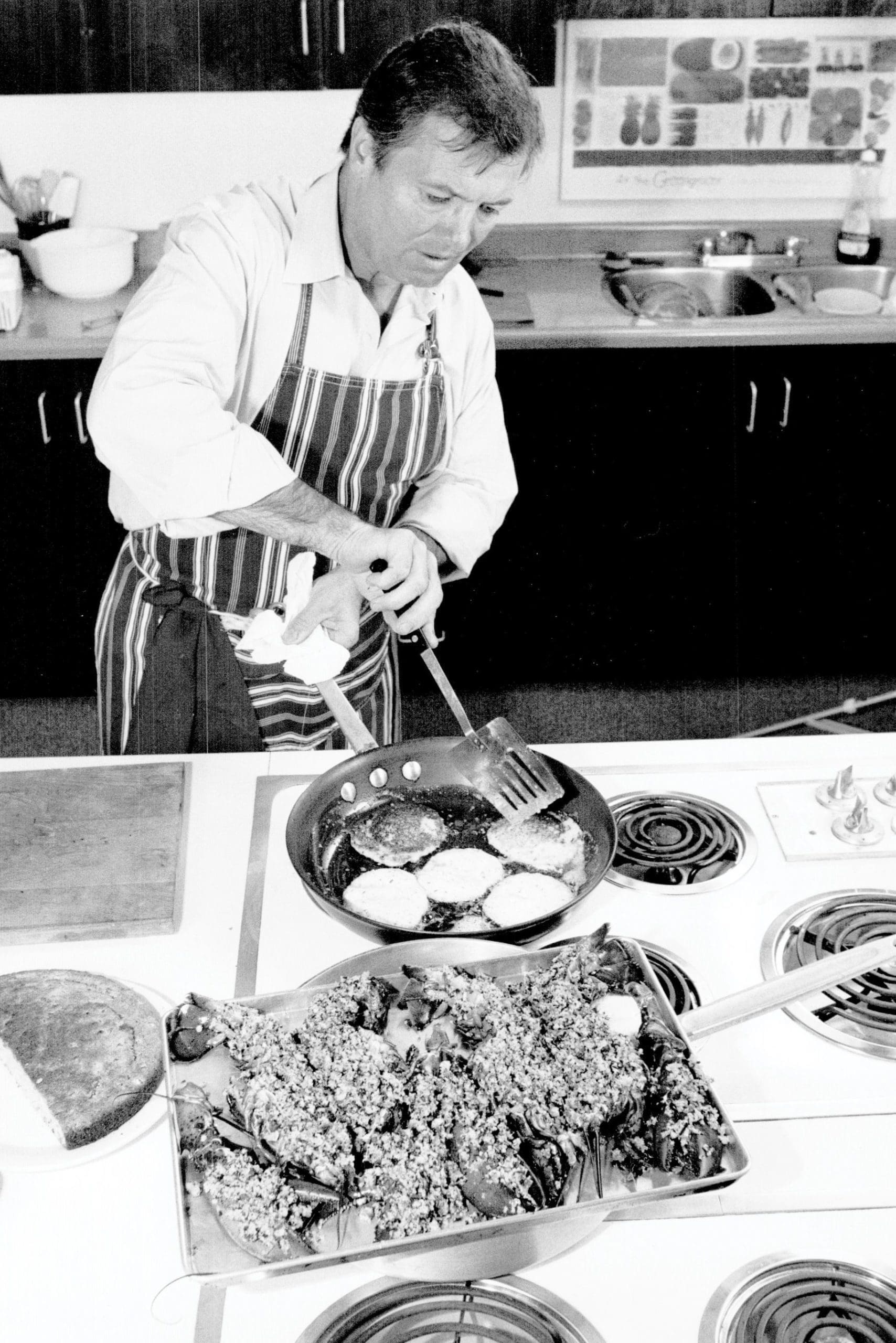

Photography by Dick Loek

Over the years, Pépin’s art studio has become his creative refuge. Set up inside his home, it’s full of stacks of colorful canvases, both finished and unfinished. He used to work at an easel, but since his shoulder injury, he finds it easier to work on a table. And while his cooking is based on years of technique, his artwork relies more on intuition.

“I’ve been painting since the early sixties, and I can look at those works today and I would not know where to go to do this,” Pépin muses. “It’s not the way I think now. It’s not good or bad, just different. I would love to be able to taste the food I made 60 years ago. I’d probably say, ‘Wow.’ Food is very reticent. You eat it, and it disappears. But the painting remains, and you can look at it. So there is a difference.”

“Chicken and Herbs” by Jacques Pépin from Art of the Chicken published by Harvest Books (2022)

Throughout our interview working in the background and sometimes chiming in is longtime colleague Tom Hopkins. For nearly 40 years, he’s been the chef’s photographer and curator, even setting up a website to sell his paintings. Pépin is known for his frugal approach to cooking, often freezing discarded chicken skins for later use. Turns out, he’s just as thrifty with art supplies. “I used to paint five or six times on the same canvas, but now Tom won’t let me do that anymore,” Pépin smirks.

Surrounded by friends and family, the master chef has simplified his life, summing up and savoring. He is poetic in describing his lifetime with food and how memory colors our everyday existence. “Certainly the food you have as a child is very visceral,” he remarks. “Those tastes stay with you, and at some point, they become more than the taste of food. They become love, security. Those foods will stay with you for the rest of your life.”

Photography by Washington Post via Getty Images

Maybe that’s why Pépin is paying homage to his beloved chickens. In a sense, the prized birds of his childhood set him on a course of culinary excellence. And he’s loved every minute of it. “Really the secret to life is simple,” he concludes. “If you can make a living out of something you love to do, then you never have to go to work.” Spoken like a true bon vivant.

Chicken Bouillabaisse

One of the great culinary memories of my youth is when I first tasted bouillabaisse. My father had taken me to a small bistro called a bouchon in Lyon, where the chef/owner was known for his fish dishes. Bouillabaisse is a famous fish stew from Marseille in the South of France, made with many different types of rockfish like red mullet, scorpion fish, and especially rascasse (hogfish) and sometimes langouste (spiny lobster). The stew is flavored with saffron, garlic, onion, tomato, fennel, thyme, white wine and Pernod. It is served with a rouille sauce — a mayonnaise loaded with garlic and flavored with the broth from the fish stew, which lends the finished product a deep reddish color.

A few years ago, I decided to make a bouillabaisse de volaille. In my recipe, I replace the fish and shellfish with chicken and sausage but keep the same flavoring ingredients. I first marinate the chicken pieces with olive oil, saffron, garlic, onion, carrot, celery, herbes de Provence, and salt and pepper. When it is time to cook, I cover the mixture with white wine, tomato, hot sausage, and potatoes, and let it simmer for 45 minutes. Meanwhile, the rouille is made in a food processor by emulsifying egg yolks, garlic, salt, black pepper, cayenne pepper, and some liquid and a potato from the stew. The mixture is finished with a generous addition of the best-quality olive oil available, which creates an unctuous sauce, full of flavor. It’s a different, delectable spin on a classic and yet another delicious way of enjoying chicken.

My Home Version of HoJo’s Southern Fried Chicken

I had never encountered a dish prepared quite like the chain’s famous Southern fried chicken, with its delicious crispy coating. We used a piece of equipment I’d not seen before, a combination deep-fryer and pressure cooker. I enjoyed that chicken so much that I often duplicated the dish at home, making a few adjustments for a non-industrial kitchen.

I began by cutting a chicken into pieces and soaking them for 24 hours in buttermilk and a bit of Tabasco sauce. While I heated lard and peanut oil in a large cast-iron skillet with a tight-fitting lid, I shook the buttermilk off the chicken and rolled the pieces in flour mixed with a little baking powder — making in essence a self-rising flour. When the fat reached 325°F, I dropped the chicken pieces into the pot and put on the lid to replicate the moist conditions of the pressure cooker for 20 minutes or so. The result: chicken at its most succulent.

Julia and Jacques’s Dueling Chickens

Julia and I never could agree on the proper way to roast a chicken. Julia liked to give hers a generous rubdown with butter before putting it in the oven. She called this step a “butter massage.” She also found no need to turn a chicken in the oven and roasted birds weighing less than 3½ pounds breast side up for the entire time. Julia liked to roast her chickens on a V-shaped rack in a shallow roasting pan about two inches deep, contending (rightly) that this method let the heat circulate around the bird for even browning.

I, on the other hand, think it’s important to start the chicken on one side, flip it to the other side, then turn it on its back for a stint, during which I baste it frequently with pan juices. The meat around the juncture of the thigh and drumstick needs the most cooking, and with the bird on its side, that joint is in direct contact with the heat and the skin becomes golden and crisp. But you must cook it in a heavy-bottomed roasting pan that allows for good heat diffusion.

Julia and I agreed that whichever approach we took, a chicken should be roasted at a high temperature (425°F). And we were totally in sync in believing that one of the greatest pleasures in life is a perfectly roasted chicken served with a deglazing sauce made from the brown bits left in the roasting pan. I will finish by saying that both techniques yield an excellent result.

Arroz con Pollo

My wife, Gloria, loved arroz con pollo, a recipe traditional to Latin American cuisine. Gloria was born in New York City, but her father was Cuban and her mother Puerto Rican. Following Gloria’s advice, I make a version of arroz con pollo that her mother used to make. I sauté chicken pieces (sometimes I use only the wings) with spicy sausage and lots of chopped onion and garlic. I add a pinch of cumin, a few drops of sriracha, Italian seasonings and chopped fresh tomatoes. These ingredients go into a saucepan with rice and chicken stock. I cover it and cook it on the stove until the rice is done and the liquid absorbed. The key is using the right amount of rice for the liquid, which can require a bit of tinkering. Diced tomatoes and onions add their own moisture as they cook, so you have to adjust the amount of stock accordingly to achieve the desired moist, creamy and slightly sticky consistency. Gloria liked regular long-grain Carolina rice in arroz con pollo. Before serving the dish, I add some more hot sauce and shower it with a good fistful of chopped cilantro.

Recipes excerpted from Art of the Chicken published by Harvest Books (2022)

Read this article as it appears in the magazine.

An Essential Timeline of Icon Jacques Pépin’s Culinary Career.