One of the abiding rites of Upper Midwest life is leaving the Upper Midwest. I did.

For most of the 2010s I conducted an epic tryst with Mediterranean France. I fell in love with dark, fleshy wine, green Lucques olives and scrubby hills. With overripe figs, the innards of sea urchins and a red-wine stew called a gardiane made from the flanks and shins of Camargue bulls.

And then Covid struck and college tuition loomed, and like many who leave the Upper Midwest for romantic reasons, I returned for practical ones — children, family, career — that I could not quite find it in myself to regret. It was thus that I entered my late 50s: In the midst of an ambivalent repatriation. A Minnesotan, not by choice. Not not by choice.

Chef Adam Ritter is a baby-faced Minnesota farm boy with one of those smiles that looks as if he is apologizing, despite a resume spangled with five Michelin stars over three continents. He, too, had left the Midwest and come back. He was Chef de Cuisine at what is probably the best restaurant in the history of the Twin Cities: Gavin Kaysen’s Demi. Then in July 2024, he opened his own place, Bûcheron, in South Minneapolis.

In French, Bûcheron means “lumberjack,” and the ethos behind the restaurant is precisely to combine high French technique with an unassuming Northwoods hospitableness, which sounds impossible to pull off until you see it working. And it worked — a young restaurant so painstakingly conceived, so mature and self-assured, that within weeks it felt like a classic.

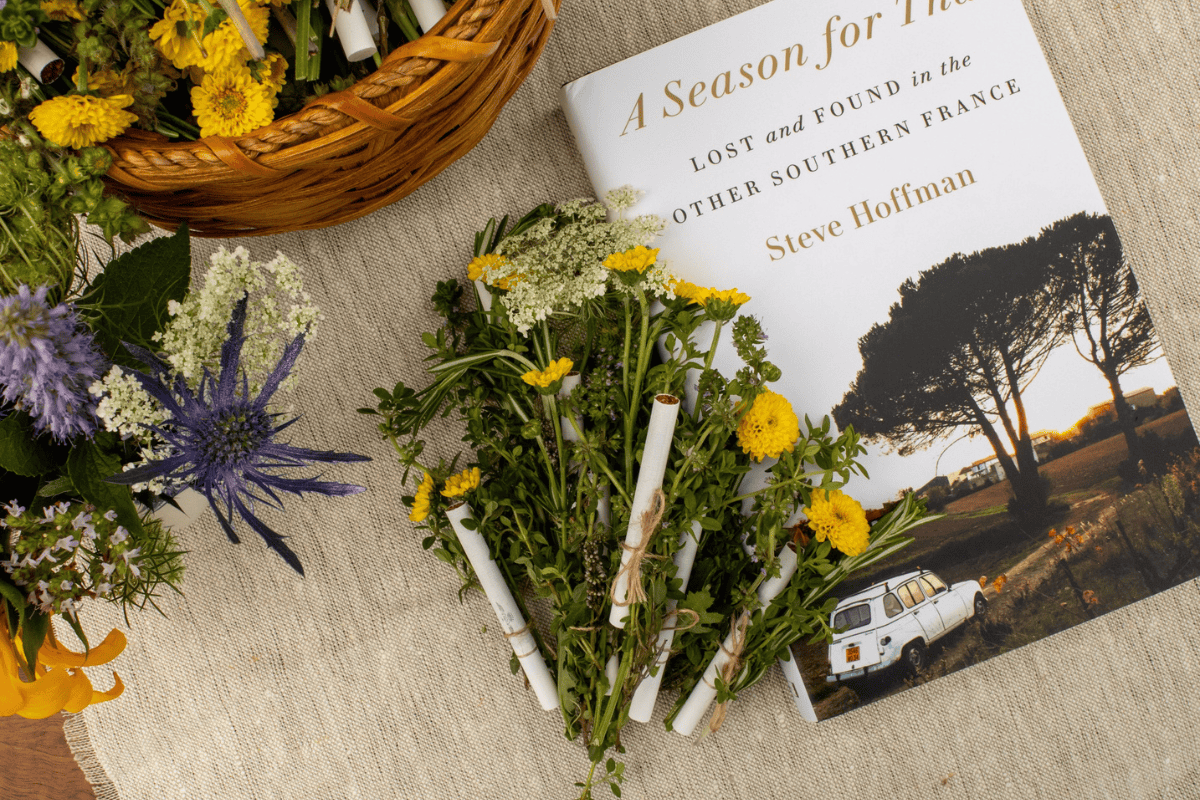

Meanwhile, I had just published a memoir about being a Minnesotan in the Languedoc region of southern France. Ritter and his spouse, co-owner Jeanie Janas Ritter, emailed me. “Let’s do a meal about your book,” they said.

I think now about all the ways the resulting meal could have gone wrong. It could have been French in the grand restaurant tradition, so unlike the rustic comfort food of Occitania. It could have been Frenchified kitsch. Berets and bal musette. It could have been a sort of Olympiad of look-what-I-can-do technique.

Most fatally of all, it could have been nice. That Minnesota version of nice that, at its self-congratulatory worst, is about good intentions and a corporate-task-force-style arrival at the second-best solution. The kind of reflexive friendliness that refuses to ask for excellence because good enough is not only good enough, but also more polite.

In the end, the meal wasn’t any of those things. I found myself in a kind of suspense all evening, willing the man on the bicycle not to fall from the high wire.

The table bouquets were crafted with herbs and foraged Queen Anne’s Lace, the wild ancestor of carrots, which grow profusely in Mediterranean scrubland and Minnesota meadows. The music was Georges Brassens and Charles Trenet, from the Languedocian cities of Sète and Narbonne.

In the way that art is always specific, the wines were not French, Mediterranean or Languedocian, but were made by a friend of mine in an 800-person village called Autignac — the village where my book is set.

The menu itself was like a meticulous translation, a retelling of the story in the language the chef happened to speak most fluently. Every detail of every dish contained a point of reference that nodded to, winked at or riffed on some detail from the book itself.

There was a very ironic cheeseburger lifted from the opening scene. There was an endive salad with puffed red Camargue rice and goat cheese from deep, deep inside the story’s fabric. The fish stew was not Bouillabaisse from the relatively distant Marseille, but Bourride from nearby Sète. On and on like this.

It was an almost unthinkable prospect: A chef at the top of his game, steeped in the alpha tradition of restaurant kitchens, voluntarily spending two nights in his own restaurant playing rhythm guitar in perfect accompaniment to someone else’s song.

I want to say it was the most completely thoughtful meal I have ever participated in and, for a number of reasons, something that could maybe only happen in Minneapolis. Because we are large enough to attract this kind of talent, but small enough for something this intimate to happen. Because we are a reservoir of quiet excellence that likes to express itself in surprising ways. Because we are a place people move away from and come back to.

He doesn’t talk about it much (in a very Minnesotan way), but Gavin Kaysen was mentored by Daniel Boulud, who was mentored by Paul Bocuse, who was mentored by Fernand Point, who was mentored by Auguste Escoffier. Kaysen in turn mentored Adam Ritter, who emerged, a little sweaty, at the end of the evening — an evening spent telling me my own story through his eyes and, in the process, offering me some brotherly reassurances about what it means to be from Minnesota. He offered me his apologetic smile and a glimpse of that quality that is maybe the very best of what it means to come from this part of the world: a real and believable humility.

“Did we do OK?” he asked.

Last month Bûcheron won the 2025 James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant in America.

They did OK. Yes. They did OK.