One artist is out to prove that cartoonist extraordinaire Charles Schulz earned his place among such greats as Van Gogh and Picasso.

In his lifetime, Charles M. Schulz rarely turned down interview requests. He found them “relaxing” and a welcome distraction from his day job, drawing the world’s most popular cartoon strip, Peanuts.

Read through some of those interviews, though, and a curious trend emerges: Schulz is quick to put himself down, downplaying his artistic nature. When Barnaby Conrad of The New York Times Magazine asked him about cartooning in 1967, Schulz said, “Cartooning is a fairly sort of proposition. You have to be fairly intelligent — if you were really intelligent, you’d be doing something else. You have to draw fairly well — if you drew really well, you’d be a painter. You have to write fairly well — if you wrote really well, you’d be writing books. It’s great for a fairly person like me.”

He frequently mentioned to reporters that his parents had third-grade educations and that he himself never finished college. When Newsday reporter Stan Isaacs asked if he saw cartooning as art, Schulz responded, “Comic strips aren’t art; they never will be art. They are too transient. Art is something so good it speaks to succeeding generations. … Comic strips are not made to last; they are made to be funny today in the paper and thrown away.”

The put downs became such a signature part of Schulz interviews that one reporter, B. Eugene Griessman of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, called him out on it: “You say you are not very sophisticated at all. Why do you say that? Is it because you’re modest or because it’s true?” To which Schulz replied, “I really think it’s true. In the first place, I don’t really think I’m especially smart. … I don’t regret not being highly sophisticated, but who even knows what it is. I don’t even think about it.”

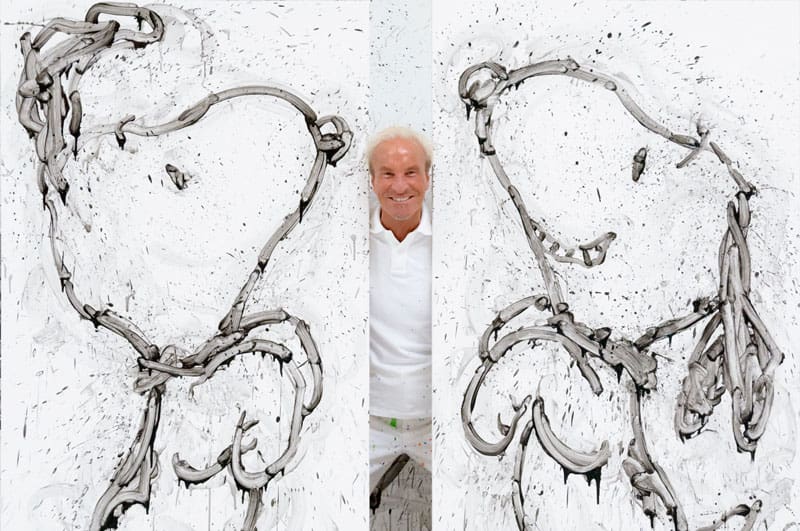

Schulz called himself “just a cartoonist.” But according to his longtime friend and protégé, it was all image-crafting. “He wasn’t trying to be disingenuous,” says artist Tom Everhart, who became very close to Schulz during the last 20 years of the cartoonist’s life. “But he was very concerned that people wouldn’t understand him.”

Everhart says Schulz was exceptionally sensitive; that to him, every perceived slight cut bone-deep. “My friend was very insecure,” he tells Artful Living. “Telling people, ‘What I do isn’t art’ and saying things like, ‘I’m not very sophisticated,’ was his way of protecting himself.”

Everhart says that, contrary to what he told reporters, Schulz very much saw Peanuts as art and himself as an artist. “Part of my job was to talk about his art,” he notes. “He would send me to explain his art to various groups of people, to say what he couldn’t.”

Fourteen years after his friend’s death, Everhart is still on a crusade to prove that not only did Schulz know exactly what he was doing but that he was an abstract master, on par with the greats: van Gogh, Rothko, Pollock, even Picasso. He has made it his mission to dispel Schulz’s own carefully crafted image as the Midwestern simpleton who drew funny-looking kids. Everhart has given more than 75 public lectures, and his own paintings revolve around this central thesis: Charles Schulz was an artist, and he knew it. Here, Artful Living examines Everhart’s case.

Everhart’s Case

Artist Tom Everhart is on a mission to make the case that his friend Charles Schulz was a self-aware artist of the highest degree. Here’s an abbreviated version of his lecture.

Exhibit A: Schulz left clues in his strip.

Exhibit A: Schulz left clues in his strip.

Even as he professed himself unsophisticated in the press, Schulz was actually very well-read and closely followed art trends, says Everhart. Thomas Eakins and Vincent van Gogh are named in Peanuts, but some references are much slier. Case in point: Schulz knew and admired painter Philip Guston and paid quiet homage to his famous closet light bulb (left) in a cartoon published shortly after Guston’s death in 1980 (right).

Exhibit B: He cultivated a form of line work that was revolutionary for its day.

Exhibit B: He cultivated a form of line work that was revolutionary for its day.

A line-work detail from Peanuts (left) and an untitled painting by American abstract expressionist Franz Kline (right). Everhart says that Schulz intensely followed the developments of the abstract expressionists in the early 1950s, when his comic strip was just a few years old.

Exhibit C: He was tremendously influenced by Dutch post-Impressionist master Vincent van Gogh.

Exhibit C: He was tremendously influenced by Dutch post-Impressionist master Vincent van Gogh.

Van Gogh’s line drawing “Enclosed Field with a Sower in the Rain” and Peppermint Patty walking through the rain in Peanuts.

Exhibit D: Schulz developed a distinctive wavy-line effect that added incredible visual interest.

Says Everhart: “Most people thought his line looked like this because his hand was shaking. Schulz himself would sometimes use this excuse. But the truth was that his pen work was incredibly controlled, and he would lightly push and pull up on his pen to get that exact wiggle effect.”

Exhibit E: Schulz believed the best line work incorporated lots of light.

“His lines move from fat to thin and then from thin back to fat — almost like a stoplight flashing at you,” says Everhart. The effect is one of dappled light.

Exhibit F: Schulz was able to explain complex ideas, such as time and space.

Says Everhart: “He told me once that every mark on a piece of paper plays with the surface. So in that way, each mark is noted by the eye individually and thus represents time.” In this way, Schulz’s Woodstock never says a word, but he speaks nonetheless.

Exhibit G: Schulz toyed with the artistic feel of his strip to such a degree that the earliest panels are virtually unrecognizable as Peanuts.

He used traditional perspective in the early 1950s. Note the horizon line with the house and trees in the distance.

Exhibit H: Toward the end of his life, Schulz became a little more frank.

In 1975, in the Peanuts Jubilee book, he printed one of his high-school report cards and this first-person caption: “This report card is printed to show my own children that I was not as dumb as everyone has said I was.” In 1999, in A Golden Celebration, he reflected on 50 years of work: “As the strip grew, it took on a slight degree of sophistication. Although I have never claimed to be the least sophisticated myself.”

In the same volume, he wrote, “There are several factors that work against comic strips, preventing them from becoming a true art form in the mind of the public. First, there is the quality of the reproduction. Comic strips are reproduced with the express purpose of helping publishers sell their publications. The paper on which they appear is not the best quality, so the reproduction loses much of the beauty of the originals. The strip is not always exhibited in the best place, and there are always annoying things like copyright stickers or the intrusion of titles in the first panel just to save space. The true artist, working on his canvas, does not have to put up with such desecrations.”

But perhaps the frankest quote of all was given to Hugh Morrow of the Saturday Evening Post in 1956. “You know,” said Schulz reflectively, “I suppose I’m the worst kind of egoist — the kind who pretends to be humble.”

From Artist to Abstract Artist

From 1950 to 1960, Charles Schulz changed almost everything about his comic strip.

He removed spatial depth. As Schulz read more about the abstract expressionists, he realized his art needed to be distilled and clarified, that he needed to remove visual obstacles and create a stronger bond of intimacy between character and reader. In the mid-1950s, Schulz began to eradicate traces of spatial depth from his strip. A Peanuts panel from the early 1950s (left) and a panel printed post-1960 (right).

He clarified his backgrounds. A panel of Schroeder’s piano in 1950 (left) and a panel from 1960 (right). “By removing perspective, Schulz brings his readers inside the strip,” explains Everhart. “It almost feels as though we are on top of that piano. Once he gets rid of traditional perspective, nothing fades away from us.”

He Picasso-ified his characters. A detail shot from “Interior with a Girl Drawing” by Pablo Picasso (left) and a post-1960 drawing of Snoopy (right). Schulz had a favorite Picasso quote: “A face has two eyes, a nose and a mouth. You can put them where you want.” Like Picasso, Schulz abstracted his characters to such a degree that when they turned their heads, their eyes wouldn’t be in the same place (creating an exceptional challenge for the animators of the Peanuts TV specials and movies). Charlie Brown is never shown riding a tricycle, for example, as his arms and legs are too short. A real-life Charlie Brown would not be able to get his arms over his head.

He stripped each character down to its most essential, expressive self. An image of Woodstock from 1950 (left) and Woodstock circa 1960 (right). Schulz told Everhart that he believed Woodstock to be his greatest achievement in character development, noting: “Woodstock demonstrates perfectly my contention that the drawing is vitally important. Abstracted cartoons can express emotions.”