In the late 1400s, the second son of Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni eschewed his family’s finance business to pursue a passion for art. Sadly though, without a patron, he was unable to support himself. Ever resourceful, he decided to craft a statue replicating a Hellenistic artifact in hopes of scoring a few quick lire. Working with art dealer Baldessari del Milanese, he enveloped the figure in stone and soil to tease a patina of age, christened it “Sleeping Eros,” and sold it to one Cardinal Raffaele Riario. Before long, the rooked Riario realized his Eros was erroneous. And while he angrily confronted the dealer to recoup his investment, Riario’s ire didn’t extend to the artist whose talent actually impressed the duped collector. Instead, he became the young man’s first patron, an excellent move given that his first name — Michelangelo — was to become among the most celebrated in the world of Renaissance art.

Fast-forward some 500 years, when the Maine Antique Digest reported the presale of a previously uncatalogued masterwork by Martin Johnson Heade. Believed to be part of the painter’s “Gems of Brazil” series, the piece sold at Sotheby’s in 1994 for $717,500. The highest bidder? Internationally renowned collector and Chairman Emeritus of Masco Corporation Richard Manoogian. Shortly thereafter, art world insiders wondered if the altruistic art aficionado, whose private collection has graced the halls of the National Gallery, had been hoodwinked. The short answer? Yes.

The Heade in question was actually a stunning forgery by Ken Perenyi, an artful dodger who sold his first manipulated masterpiece before he was 20. His faux works graced international auction blocks for three decades before he turned his palette toward less indictable pursuits. To curtail what would have been certain embarrassment, news of the fraudulent Heade was kept remarkably under the radar. It’s reputed that Sotheby’s took the piece off Manoogian’s hands, stating only that “an important Heade sold at Sotheby’s disintegrated during restoration.” Disintegrated, indeed.

Then in 2004, Sotheby’s made front-page forgery news once again when it was reported that one-time Gucci Group head Domenico DeSole acquired (what he believed to be) Mark Rothko’s “Untitled, 1956.” Having purchased the piece for a cool $8.3 million through Ann Freedman, president of the then esteemed (and now defunct) Knoedler gallery, DeSole delighted in showing off his rare find. Until, of course, it was discovered that the beloved abstract was really just a couple rectangles painted by some guy from Queens. One can only imagine the rich comments being tossed about the art world’s proverbial water cooler in the aftermath of that particular incident.

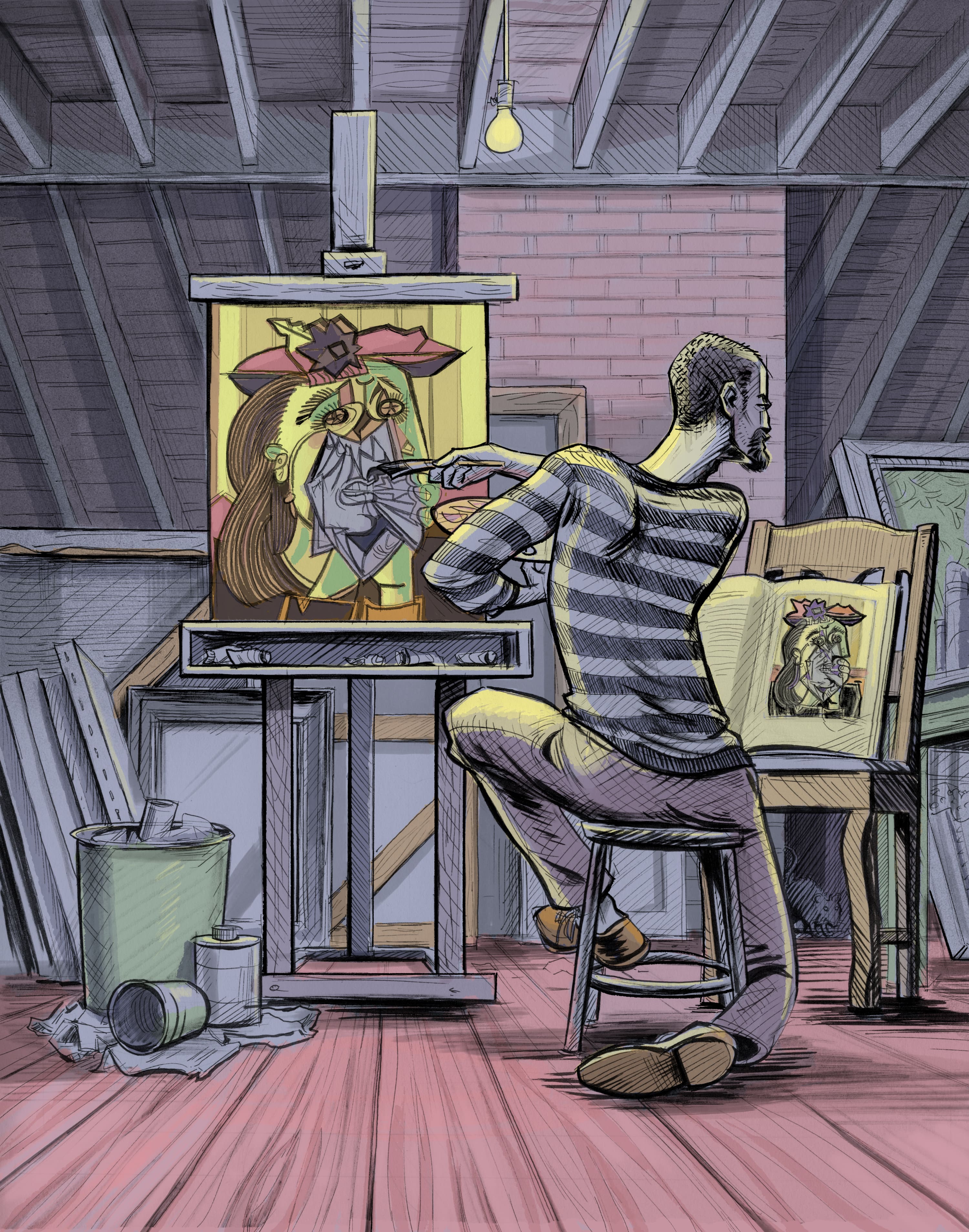

Illustration by Michael Iver Jacobsen

The case of the forged Rothko begot eight years of intense litigation focused on the Knoedler’s sale of some 40 fakes to the tune of a very real $80 million. Shockingly, Freedman was never charged with a crime despite overwhelming evidence that she was fully aware of the sketchy provenances of pieces she sold. In fact, after the Knoedler’s shameful demise, she went on to open another Manhattan gallery, which by all accounts is doing just fine despite its owner’s entanglement in past scandal. Buyer most certainly beware.

It is of little doubt that the Knoedler’s downfall played a role in the decision by Sotheby’s to be more proactive in plucking phonies off its revered block. Enter Orion Analytical, headed by scientist and art conservator James Martin and acquired by the auction house in 2016. In a display of cutting-edge sleuthing, Orion examined more than $100 million worth of artwork destined for the block in the first year alone. Yet even such grand perlustration can’t authenticate a piece of art with absolute certainty.

“A universal magic scientific technique to detect forgeries does not exist,” asserts Kilian Anheuser, head scientist at Geneva Fine Art Analysis in Switzerland. In his lab within the heavily guarded Aladdin’s cave known as Geneva Freeport, the renowned expert unravels the tapestry of doubt one strand at a time. “Analytical instruments give us only a curve with some peaks, nothing else,” he notes. In order to be useful, those curves and peaks require translation, i.e., accurate identification of chemical elements and apperception of any organic matter present.

“We have to interpret what that means for authenticity,” Anheuser explains. “For example, is titanium white in a supposedly early 1920s painting anachronistic or not? To be meaningful in a historical context, scientific results have to be historically interpreted.” But is all this really necessary if you’ve got a certificate of authenticity in hand? “Never trust any nicely printed document entitled ‘Authenticity Certificate,’” he adds. “Good expertise, either art historical or scientific, will start with detailed observation, compare it with reference data, and very clearly state the limits of its conclusions.” Still skeptical? Consider the 2013 arrest of Christian Parisot, then president of the esteemed Modigliani Institute, who was charged with providing false certificates of authenticity for nearly $8.7 million worth of bogus — wait for it — Modiglianis.

So how does a forger conceive an artwork capable of fooling even the savviest of experts? “As scientific analysis becomes more advanced, so do forgers’ skills,” says Perenyi. “As a forger, you must know as much as, if not more than, the experts to survive their scrutiny. When I would choose a particular artist to copy, it always began with a genuine appreciation of that artist. I would do research, reading everything I could get my hands on. I would post images of the artist’s work on boards to create visual flowcharts. I would spend days looking at their body of work so when I finally began to paint, I saw images as the artist did and thought like the artist did. My paintings were natural progressions. It was an evolution where I finished what the original [artist] could not.”

Like his counterfeiting counterparts, Perenyi — who, by the way, was never charged with art fraud despite a 30-year career and a five-year FBI investigation — would place important forensic markers in his work. From creating under drawings in a specific artist’s style to limiting oxidation where a canvas would have been protected under the rabbet of a frame, forgers glean from a seemingly bottomless box of tricks to successfully swindle. The best forgers submerse themselves in the science and delve into the minds of the experts. They not only anticipate but meticulously reproduce myriad telltale forensic signs.

For instance, knowing that antique varnish casts a characteristic green light when viewed under ultraviolet light, Perenyi would salvage varnish from a painting of similar age, strain it through a fine sieve and reconstitute what remained with modern varnish to create a coating that would fluoresce convincingly. Though brilliant, the method was missing one key element.

“Because there was sugar in 19th century varnish, flies were attracted to it,” he explains. “And where there are flies, there are flyspecks. The droppings are transparent at first but turn brown then black with time. It can take 75+ years for fly dropping patterns to emerge, and experts expect to see those patterns in paintings of a certain age. So I learned how to make aged fly droppings by mixing epoxy glue or thick linseed oil with color pigment then applying the mixture with a pin to create patterns of raised black dots.”

In addition to physical attributes, the provenance of artwork can and does support authenticity. So it would be reasonable to assume that a work with multiple, well-documented transfers through respected auction houses has been thoroughly authenticated somewhere down the line, right? Not so fast. Perenyi readily admits that to this day he still occasionally spots one of his paintings in an auction catalogue. “It’s like seeing an old friend,” he quips, before noting he wouldn’t embarrass the seller or the buyer by raising a red flag.

So, what’s a collector to do? “Your homework,” notes Anheuser. “Have a close look at as many authentic objects from your collection area as you can: in museums, at art fairs, in your friends’ collections. Use a magnifying lens or a stereomicroscope if you have one. Try to figure out exactly how the object was made: What tool marks can you see? How would you make it yourself? Talk to conservators; they spend hours, days and weeks looking at objects at close range, touching and feeling them. Talk to experienced collectors, museum curators and gallery owners, who have a wealth of experience to share. And never buy under pressure, especially if you’re new to art. It’s better to lose an object than buy wrong. Life has plenty of opportunities.”

If we’ve learned anything from the spectacular forgeries of the past, it’s that despite all due diligence, it’s still entirely possible for even the most learned art lover to be duped. And should you find yourself on the raw end of a forged artwork deal, what should you do? “Collect as much information as possible and bring the painting back to where you purchased it,” Perenyi says. “And if you bought it at Sotheby’s, tell them Ken sent you.”

How to Spot a Fake

Six common-sense tips to avoid being taken.

Google It

Sophomoric, perhaps. But it’s worth taking a moment to check if the painting you have your eye on is already part of an auction or collection. In 2000, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s offered Gauguin’s “Vase de Fleurs” for sale at the same time. The Christie’s version was declared a fake, while Sotheby’s went on to sell its for £169,000.

Check the Back

Inspect the back of the painting for labels or marks suggesting the piece has passed through galleries or auction houses. Then call these institutions to ensure the artwork did in fact come through them. You can also check markings on the back of a painting against photos in official archives; lesser, amateur forgers typically focus only on the front.

Know the Artist

For instance, did the artist prefer tacks or staples? In the 1940s, some artists started using staples rather than tacks to secure their canvases to stretcher bars — some, but not all. A notable exception? Jackson Pollock, who said, “I hardly ever stretch my canvas before painting. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface.”

Look for Clues

Cheap forgers have a penchant for cheap materials. The old masters used quality brushes that didn’t leave behind errant bristles, while forgers have been known to opt for less expensive tools that can shed tiny hairs.

Sniff It Out

With age, the original paint used by an artist will cure completely. A new forgery, however, can retain the smell of paint. While you may get an odd look or two when found (literally) sniffing around a painting you admire, due diligence has its own reward.

Face Reality

Finally, if it seems too good to be true, it is. If you were offered a brand-new, fully equipped Bentley for $10,000, you’d know something was awry. The same goes for art. Work by known artists sold for far less than market value is sketchy at best, despite how alluring it may seem.