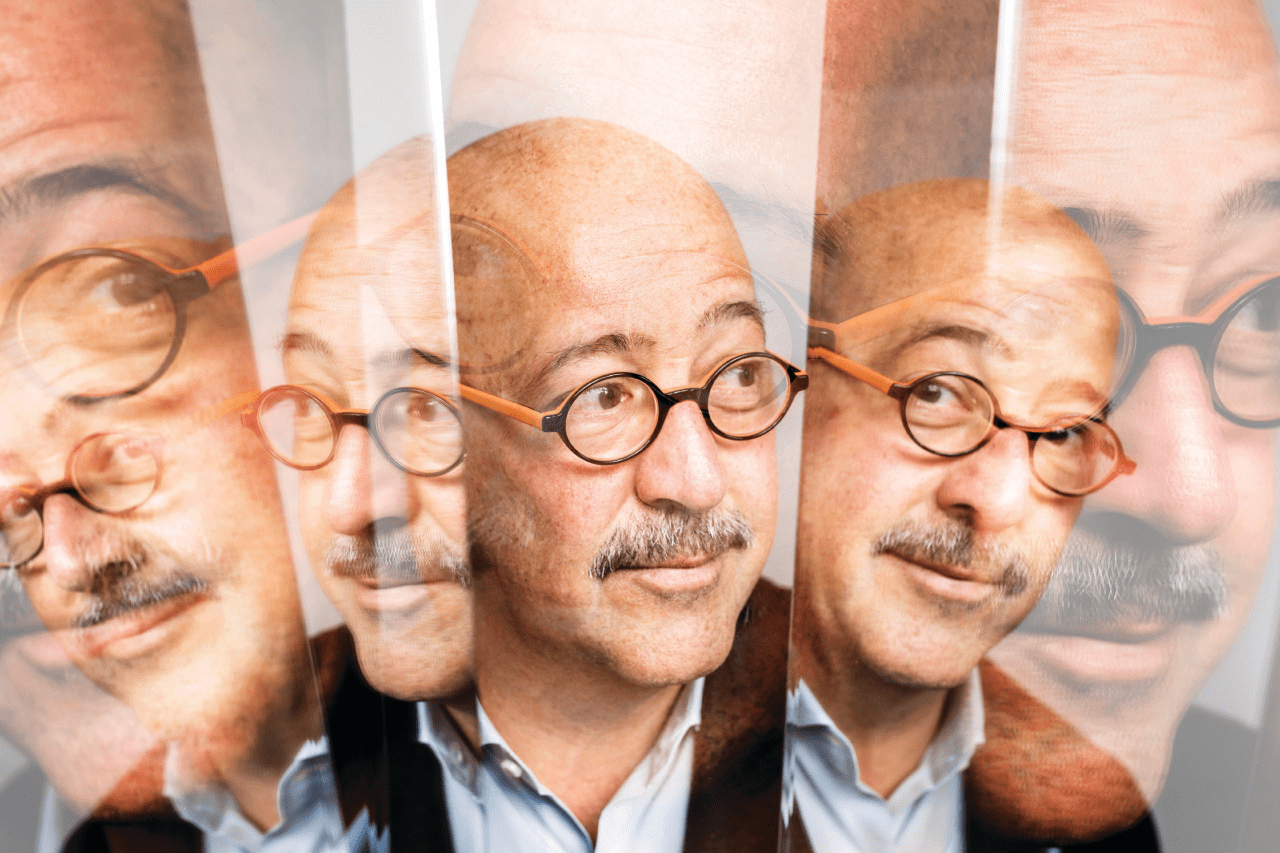

Photography by Brandon Werth

Andrew Zimmern is something of an enigma in the food world, shape-shifting from celebuchef to restaurateur to food critic to television personality to content creator to culinary teacher to children’s author. But long before the 57-year-old was eating giraffe weevil on Bizarre Foods or combatting the controversy surrounding the opening of Lucky Cricket, he was facing a different kind of battle: one against his inner demons and his addictions. In a terribly and wonderfully candid interview, he spoke about the trauma that set it all off, the time he tried to drink himself to death, the constant work he does to stay sober even today and everything in between.

On his childhood:

“I was raised in New York City in a privileged surrounding by most conventional standards. My parents had divorced but were best friends. I had a lot of healthy role modeling. But I never felt comfortable in my own skin. Even as a little kid, I remember never feeling like I really fit in.

When I was 13 and was away at sleepaway camp in Maine the summer of ’74, I tried smoking pot. I had tried booze a bunch of times — stealing sips out of my dad’s drinks, drinking with my cousins on holidays. When I tried smoking pot, I didn’t have any euphoric feeling at the time, but I knew I was onto something.”

On what sparked his early addictions:

“When I returned to New York City in August of ’74, my father picked me up at the airport, and we drove to the hospital. My mother was in a coma for several months as the result of a misstep in surgery; she had been given the wrong anesthesia, which cut off the oxygen supply to her brain. She had suffered some severe brain damage.

At 13, I walked into this room and saw my mom in a plastic oxygen tent. It was an extremely traumatic event in my life, one that has affected me greatly up until even a couple years ago, when I started doing some serious trauma-related work.

But my dad was of the Greatest Generation. He was in the navy in World War II and helped build a business in New York City. We were going to deal with this by having a good cry now then maintaining a stiff upper lip — life goes on. He did the best he could, but in retrospect, it wasn’t enough.

I found myself in the Upper East Side apartment where my mother and I had been living with a nanny and a housekeeper, and my father returned to his apartment downtown. And I very quickly became overwhelmed with the myriad feelings and situational changes. I was also overwhelmed by the outpouring of grief and compassion from family and friends. The tragedy just grew to really titanic proportions in my head. I certainly didn’t want to be feeling what I was feeling.

Now, this was in 1974; times were different. We had a family charge at the drugstore on the corner. We had a wad of cash in the silverware drawer for emergencies. There was a charge at the liquor store. There was a fully stocked bar. I had friends who had friends who sold weed and other drugs. So I started drinking and smoking pot regularly. And it was at that time that I felt that euphoric sense of relief.

I had found my coping mechanism. I felt like I had armor on. If the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, and my tool was drugs and alcohol. So that became my way of living.”

On his addictions spiraling out of control:

“I very quickly started doing pills, cocaine, hallucinogens. By the time I went to college, I had already experimented with heroin. So when I got to college, the gloves came off, and I became a typical New York garbage head. Whatever was around was my drug of choice. I liked to mix things that brought me up with things that brought me down so that I could use all day long, whether that was narcotics, sedatives, opioids mixed with cocaine. I was functional, which gave me the false illusion that it was manageable. But things just continued to get worse and worse.

I had several required leaves from school. The third week of my freshman year, I woke up in a hospital room. I wasn’t used to the heavy drinking of the college scene, so the technical reason for my hospitalization was alcohol poisoning, but in reality, I was on a massive cocktail of lots of things. I was released from the hospital, there was a campus police report, and I was required to go for a drug and alcohol assessment.

I took a bunch of tests, and the counselor, a gentleman named D.B. Brown — I’ve never forgotten him — talked to me for an hour. He told me that on the Jellinek Curve, which is one of the tools that measures if you are an addict or an alcoholic, I was already at a chronic level. At 18.

I told him to go screw himself. I was 18 and in college. I felt like I was Superman. This wasn’t a problem; this was a situation. During my blowouts at school when I was required to take semesters off, I would go cook in Europe. I did pretty well. And I found an industry where a lot of people with my issues were comfortable, sort of hiding out in a sense.

One of the many characteristics of alcoholism and drug addiction is hyper-responsibility versus hyper-irresponsibility. In my case, I could show up to work and kick ass because I was so competitive. Then at night, I’d go out to these underground clubs or to someone’s house where we’d just get high all night long then go to work the next day and function beautifully. But there would be newspapers sitting around my house that were a year old. There were bills that were just left unpaid. Somehow I managed to sort of walk between the raindrops during college and ended up graduating.”

On how it all came undone:

“I had made a bit of a name for myself as a talented young culinary in New York City and had a series of fantastic jobs. I chefed in restaurants, general managed restaurants, helped start a bunch of restaurants, even worked for the city’s top public-relations guy for six months to learn that side of it. My goal was to have my own restaurant group at some point.

Along the way, although my work life was going great, my alcoholism and drug addiction were dragging me down the other way. Ultimately, the addiction always wins out. And in 1990, everything came undone.

I stopped being the funny guy at the party and started being the scary guy at the party. I would get calls the next day and instead of hearing things like, ‘Oh my God, we got so drunk. You were so hysterical,’ it was, ‘Dude, that was really awful. That really scared me. I’ve never seen you that aggressive or violent before.’

By that point, I was leading quite a triple life. I had my professional life during the day. I had my life with my friends that I was desperately trying to hold onto. Then I had my secret after-three-in-the-morning life. First you’re out with your friends. You go out to a show; you go to a bar. But then everyone has had enough and goes home. That’s when I would go to the underground hellholes where people who can’t stop, who’ve lost the power of choice, who’ve lost control, who’ve lost manageability wind up. And all of that caught up with me.”

On his year of homelessness:

“By December 1990/January 1991, I was evicted from my apartment. I had no one to call, no one’s couch to crash on. Everyone had had enough. So after I got evicted, I put a bunch of my stuff in storage with the last of my money then went to the Blarney Stone and started drinking with the same drunks who were always there at two in the morning. They asked me what was new, and I told them I didn’t have a place to live. They told me to go talk to Bobby.

Now Bobby was part of a bottle gang. When the Blarney Stone would close for a couple of hours, people would buy a bottle at the all-night liquor store and drink in the alley around the corner. Bottle gangs were fairly prevalent then, and they still are. He told me, ‘We have a building down on Sullivan Street in Lower Manhattan.’

So that night I took my duffel bag with some clothes and some of my possessions and slept in this abandoned building on Sullivan Street. It was a townhouse that was in the midst of being renovated. Work had stopped. Actually, demolition is more like it; renovation is a little too fancy a term. There were concrete casements in the windows. There was electricity that had been pirated from a nearby building across the roof with extension cords. And there was a sink with running water, so you could drink water. Thus began my year of homelessness.

I didn’t shower for a year. Every night, I slept on a pile of dirty clothes on the floor that I called my bed. I didn’t really sleep; it was more like passing out. Every couple days, I would steal a bottle of Comet cleanser that I would pour in a circle around my sleeping area so rats and roaches wouldn’t crawl over me in the middle of the night.

And I thought that was OK and normal. That’s how bad it was. And I just kept falling further and further down. I would steal purses off the backs of chairs in bistros on the Upper East Side and bring them downtown to drug dealers to sell the credit cards and passports for money. That was my life.”

On the time he tried to drink himself to death:

“There were winners and losers in life, and clearly I had lost the game of life. I convinced myself that the easiest way to deal with the guilt, the shame, the unaddressed trauma going back to my childhood would be to drink until my body broke down.

So I stole some jewelry from my godmother, hawked it, got a little pile of cash and checked into this hotel called the San Pedro, a grade above a flophouse. I then went across the street to the liquor store to buy a couple cases of — I’ll never forget it, Popov vodka had come out in plastic bottles and I remember asking for a third case just because it would be light enough to carry upstairs. I never actually broke into the third case. I started drinking around the clock and blacking out.

I couldn’t tell you whether it was three or five days later, but I woke up one morning and the tension, the Ace bandage that had been tied so tightly around my entire life just wasn’t there. I felt a desperate need to reach out to someone. I called my friend Clark, who was shocked to hear from me. He came down and got me out of there. Unbeknownst to me, he was already planning my intervention.”

On his intervention:

“I walked into my intervention the afternoon of January 28, 1992. Some people wanted to say some stuff to me. I had a choice and a plane ticket to Minnesota. And everybody wanted me to get on that plane and go get help.

It wasn’t until several weeks later that I saw it for what it really was. The most caring and compassionate thing that you can do for another human being is sprinkle them with dignity and respect, and show them that you love them. That’s what human beings need to get well. It was an incredible act of profound kindness. At the time, I was so emotionally beaten down, I just couldn’t stop crying. All the quit had left me. I had always been fighting everything my whole life. One of the hallmarks of recovery is that at some point, you have to bottom out, and I really bottomed out that day.

The day before that, Clark had asked me, ‘What are you going to do?’ And I said, ‘Well, if you just lend me a little money, I could get this job. I’ll go to this meeting. I’ll see this doctor.’ And I was hustling and shucking and jiving and lying. And just 24 hours later, walking into that room, I realized I didn’t want to live the way I had been living.

My parents, teachers, doctors, friends, friends’ parents, lawyers, shrinks and eventually judges — everyone had been telling me the same thing for almost 20 years: You need to stop drinking and drugging, and start addressing these things in your life — and I am here to help you. People want to help other people. That’s how we’re hardwired as human beings. I had thousands of life jackets thrown to me while I was drowning, and I just kept throwing them back in the boat. That night, I put on the life jacket, and I wound up at what is now Hazelden Betty Ford up in Center City.”

On getting treatment at Hazelden:

“I spent five weeks at Hazelden. The first couple days, I was on the medical board while they detoxed me and made sure I was physically safe enough to go to a unit. When I got down to my unit, I was so ready to be done with this phase of my life that I just said yes to everything. I attended every group. I attended every lecture.

And I found myself with a solution put in front of me very quickly: the 12-step program. Everything in the literature, everything people were telling me was that my success really hinged on a relationship with something bigger than myself. It could be the great spirit, it could be a tree, it could be the ocean. It’s not a religious program; it’s a spiritual program. And one thing everyone had in common was that they had stopped living their life on a me-me-me basis and started living in an other-centered fashion.

My whole life, I thought there was nothing bigger than me, which was pointed out to me many times during those first couple weeks in treatment. All I had to do was look at my own story. My best thinking and acting had gotten me to this horrific place in my life where I had bottomed out, crashed, almost died — and wanted to die.

I could admit I had a problem and that my life was unmanageable, but the idea that something other than me was going to help me get well was like Greek mythology. I just didn’t feel like there was any way I could achieve that. You’re just really waiting for this grand gesture, this big-picture, white-light, burning-bush thing to happen to you.

Much more commonly, though, you have an experience as the result of doing the work that’s laid in front of you, especially early on. You have a spiritual experience that’s more of what the great Dr. William Silkworth called a learned experience. And I was like, ‘I’m a good learner. Maybe I can get this. Maybe this will happen for me.’ That really set me on my course for staying clean and sober now for a long time.

I had heard for several weeks from different speakers how important it was to get a sponsor early on. So I asked one of the speakers if he would sponsor me. He gave me his number and told me, ‘Call me when you get down to the Twin Cities, if that’s where you wind up.’ My relationship with him is now 27 years old.”

On living in a halfway house:

“When I left Hazelden, the recommendation was four to six months in a halfway house they run called Fellowship Club on West Seventh Street in St. Paul. I had nowhere else to go. I had no other plan. I had no other opportunity. I had nothing. So my answer to anything anybody told me was yes.

One requirement of the house was that you got a job right away. So I spent a day writing this business plan about remaking the food program at the halfway house and presented it to the director. And I got laughed out of the office. They told me, ‘Go get a regular job, something that’s nine-to-five that you can leave behind so you can focus on your sobriety.’

Ultimately, if you don’t get a job, they find one for you, because it’s a requirement for staying in the house. There were a lot of construction and cleanup companies that knew there was a reliable source of labor in certain pockets around the Twin Cities, like our halfway house. So on the third or fourth day, I wound up cleaning toilets at a hospital. So there was a lot of motivation the next day to get a different job. I then went to every food-service establishment I could walk to or could take a short bus ride to, and I found a job washing dishes at a diner on Snelling Avenue that’s no longer there — Dubin’s.

Then I applied for a dishwasher job in a restaurant that some people I knew from New York City were opening. The French partners who own the Theater District restaurant Café Un Deux Trois opened one in the Foshay Tower in the spring of ’92. Some people I knew in the recovery community got jobs there as waiters, and I applied to be the dishwasher. And I just transferred my awesome dishwashing skill set from Dubin’s to Café Un Deux Trois.”

On the importance of halfway houses:

“Some people need to be rehabilitated. I needed to be habilitated. I needed to learn how to live. I had my dishwasher job. I was going to meetings. I started having moments where I was extremely joyous. But I was in a safe and protected place to take the baby steps I needed to take.

That’s why halfway houses and transitional housing that supports people with mental-health issues are so important to me. Because you need to let people who are really sick or who have been traumatized have a safe place to take those baby steps and get well.

Today I’m on the boards of some important organizations that help a lot of people in this country. And I try to make a difference in the lives of people with whom I can share my experience. It doesn’t matter if someone is a homeless veteran. I’m not a veteran, but I’ve been homeless, and I know what that trauma feels like.”

On the time he almost relapsed:

“I remember one night two, three months sober, being in a car with some guys coming home from a meeting, and they were looking to buy cigarettes. In those days, there were machines in bars, and some bars sold them from behind the counter. So they stopped outside this bar, and I told them I was staying in the car. I remember I was the only one in the back seat. There were two guys in the front seats, and they got out and walked into the bar. They were probably back in two minutes with their smokes.

And I sat there staring at that bar. I just kept saying, ‘Stay in the car. Stay in the car. Stay in the car.’ Because I knew if I got out of the car, I was going to drink. It was just staring me right in the face. I couldn’t go in. It really speaks to the idea of, ‘What is my reason for being here?’ Because at that point, I was working as a dishwasher in a restaurant that had a full bar, but I never felt like drinking there. You never know when you’re going to be challenged. But if you have a good reason and you have a plan, you can get through those early stages.”

On maintaining his sobriety:

“Quite frankly, my experience has been that if you are taking your medicine, you don’t get sick. And the recommendation of millions of people with more experience than me was, ‘Don’t drink. Go to meetings. Do the work.’ It’s almost like the kindergarten rules that I had ignored as a child. But once I started paying attention to those, it was like all of a sudden I had been jolted with electricity.

And then in a healthy way — and I mean this in the healthiest way possible — you become so attached to other ways of making yourself feel good. I devote 25% of my time and probably just as much of my money to doing things for other people. I would love to say that I do it solely because I want to be helpful to other people, but I do it because it’s the recipe for success in my life. When I’m doing service work, I’m taking my medicine that makes maintaining my sobriety almost no work at all. Now, that’s after a long time. But I’m still active. I still regularly attend 12-step meetings. I still do all of it. It’s changed over time, but that’s very typical with sobriety in my experience.”

On how his addictions sit at bay inside him:

“Drinking, drugging and all these -isms are progressive diseases. They lead to jail, institutionalization or death. They never get better. They never go away for the real addict. They’re always with you. They may be dormant; they may stabilize for awhile. They give the false illusion of being manageable and make you think you’re fine. But it’s a progressive disease.

I believe we are all just an arm’s length away from that next drink or drug. My disease has not gone away; it’s just dormant inside me. I have to remind myself that my disease is just in there exercising and doing pushups, waiting for me to stop doing the things that keep me well. But I also know that as long as I keep doing the things that keep me well, I’m going to stay well.”

On addiction in the hospitality industry:

“I’ve seen studies that put the hospitality industry at No. 1 or No. 2 in substance-abuse rates across all sectors of employment. I think that’s for a lot of reasons, but first, there are a lot of transient workers. Everyone always thinks we’re talking about fancy restaurants, but this is across all of the hospitality industry. So you’re talking about some of the lowest paying jobs in America. The hospitality industry is also the No. 1 or No. 2 employer of single parents and the No. 1 employer of people transitioning out of jails and institutions. So the population that you’re selecting from is one issue.

But I think the more important piece of it, at least in my experience, is that these are environments where you can hide out. If you want to hide out, you can find a place in the restaurant business. For generations, our industry has been plagued with -isms: alcoholism, drug addiction, toxic masculinity, emotionally abusive environments. Restaurants have had to do a lot of work over the past 10 years and are still doing a lot of work to clean themselves up.

By the same token, there are very positive things about the hospitality industry: the sense of family, the bonds that are created through this intense kind of work. That has rescued a lot of people, which is my story. Restaurants rescued me and gave me my life back.

But it’s that same competitive, emotionally abusive environment. It’s that same intense combat arena. Whether it’s cleaning rooms in a hotel or peeling potatoes in a restaurant, there are four people doing that job. And the person who’s the slowest is not going to have a job the next week. It’s a meritocracy oftentimes managed by people who have no idea how to manage a meritocracy.”

On addiction as a public health crisis:

“As a society, we have a choice: Do we want to take care of everyone? Do we believe that everyone should have the same fair start? Do we believe that everyone deserves the same grace, dignity and respect? As the late great Senator Paul Wellstone once said, ‘We all do better when we all do better.’

The idea that someone else is going to fix this problem doesn’t work. Because alcoholism, chemical dependency and all the other -isms touch every single family in America. There’s not a family in America that’s immune to these -isms. This is a national mental-health crisis because of all the dollars that flow through our healthcare system and how much of the mental-health parity laws are yet to be equalized. If you break your leg, you can go to the hospital and get it taken care of. If you have a mental-health issue, good luck.

Until we solve that problem, we are all responsible for a massive public health crisis that I believe we are living in right now and are largely ignoring. Healthcare costs in this country are soaring. And there’s a significant amount of those healthcare costs that we as taxpayers are paying for that is a direct result of mental-health issues like alcoholism and drug addiction. They’re mental-health issues. They’re also physical-health issues. And we pay for it all on the back end.

Wouldn’t it be better if we had mental-health parity laws that could help get people into the appropriate places early on? Wouldn’t it be great if we were able to provide affordable drug and alcohol treatment to everyone who needs it?

I think it’s shameful. Actually, it’s beyond shameful. It’s criminal. And I’m choosing my words carefully here. I don’t think it’s too dramatic to say that ignoring our fellow Americans in need and watching them die when they could have been helped is its own form of genocide. I think ignoring these crises in our country is bordering on criminal at this point.”

On the opioid epidemic:

“The Big Pharma financial stranglehold is a big part of the problem. You have drug dealers with diplomas on the wall in white lab coats with stethoscopes around their necks.

As a sober person, I’ve had medical situations that have required me to take painkillers. I had a really horrific burn on my hand about 18 years ago. And the first thing they did in the ambulance was throw a painkiller down my throat. Then, I get out of the hospital 12 hours later, and the doctor writes me a prescription for 24 codeine pills and says, ‘This is good for six days, and you’ve got three refills.’

Thankfully I had a plan. You always have to have a plan. I said, ‘First of all, get rid of the refills. I’ll take six pills. If I need more, we’ll call you.’ Then I handed the bottle to my wife. Because who knows what my brain is going to tell me when I’m in pain in the middle of the night? Shit, I’ll take two and snort two more. We have gotten to the point where people are being overprescribed drugs that are much stronger than they need. It’s pretty bad.”

On Anthony Bourdain’s suicide:

“I was in Philadelphia. It was a Friday morning. We had been out really late shooting Thursday night, so we had an 11 o’clock start. We’d been doing nine, 10 long days in a row, so I decided to sleep in. I set my alarm and turned off my phone ringer for the night.

My alarm went off and I grabbed my phone to turn it off, and I almost vomited because I had maybe 80 missed calls and 220 texts. I just had never seen anything like that before. And that could only mean one thing: Something horrible had happened to my child, and the whole world was trying to get ahold of me.

But then when I tapped my phone, I saw a news notification with Tony’s name. Then I tapped my messages, and it was every food writer I knew, every culinarian, every mutual friend. I was stunned, absolutely stunned.

I started to read some of the notes, and I started to cry. I called my crew and said, ‘We’re not going to work today at 11. I need some time.’ It was just an awful, awful, awful day. It wasn’t until many hours later that the shock… because your first… this is someone you know. He’s your friend. There’s stuff to do, people to call. Then as the day went on, we were reminded what a symphonic presence he had and how culturally important he was to so many people. And the shock — I still can’t believe he’s not with us.

On the insidious nature of suicide:

“Now, Tony could afford mental healthcare. But I think it just shows you how insidious so many of these mental-health issues are. Many mental-health issues have a component of their symptomology where the afflicted person’s brain tells them they don’t have a problem. With alcoholism and chemical dependency, we call it denial. But there are a lot of other mental- and physical-health issues that have a similar component.

Several weeks after Tony’s death, we had the Aspen Food & Wine Classic. Kat Kinsman, who started an online group called Chefs With Issues, organized an awareness raiser for chefs to talk about this and to let people know if they’re struggling there are options. Several of us in the food industry who are in recovery helped facilitate that meeting. Then several weeks after that meeting, an Aspen bartender and line cook killed himself.

When I heard about it, it made me angrier than I have been in a long time. Here we have the attention of a nation focused on the deeply sad loss of a treasured icon, and it should be the church bell around which we all go running to convene to solve this problem as best we can and to provide resources and help so that other families, other friends, other people don’t have to find themselves in this same situation.

Unfortunately, I know a lot of people who have killed themselves. It’s not an instantaneous thought, feeling and reaction. It is something that is evil and pernicious that’s inside of you. It just underscores how much help we need to give everyone.

Can we save everyone? No. I didn’t have to go to my intervention and get on that plane and go to Hazelden. If I hadn’t, I would have wound up dead. We’ve lost a lot of people who, when you investigate the stories of their lives and learn what was really going on, were thrown a hundred life jackets just like me and kept tossing them back. I’m especially sensitive to this because I know that if I hadn’t put on that last life jacket, I would have been one of those anonymous deaths like that bartender in Aspen.

We have a national health crisis on our hands. Teen suicide rates are climbing at the greatest pace I believe since we’ve been recording the data. If this isn’t a clarion call for people to understand that it’s not up to somebody else to do something, that it’s up to us to do something, then I think we are dishonoring the loss of all of those people who aren’t with us anymore who should be.”

On what to do if you are facing addiction:

“I live my life very transparently for a reason: because I have to. Because we’re only as sick as our secrets. At various times in my life when I was unwell, it always revolved around secret keeping. It’s one of the first hints that you’re starting to compartmentalize and not living life on an other-centered basis.

What I tell people is that you have to find someone to talk to. You have to somehow summon the courage to ask for help. You have to share that dark, painful thing that you never want to tell anyone. Because until you do, it will always have power over you. The reason that so many people don’t is that they feel they will be rejected, that they won’t be understood. Their secret will be out. Which is why affordable mental healthcare is so important.

I’m oftentimes jealous of people who are very into organized religion, because there are mechanisms within that. I’m not advocating for any religion over another, but all of them have built-in mechanisms where people are in regular attendance at a church, a synagogue, a mosque and can interact with other people of faith and with faith leaders. So you can reach out and say something. You have to let somebody in. That’s the toughest thing in the world — to let that first person in.

The other thing I tell people is that there’s not a human being who walks through life between the raindrops, who doesn’t have issues, who hasn’t done things they regret, who doesn’t carry around varying degrees of shame and trauma with them. Everyone can relate. I’ve never heard a story of someone who turned to another human being and said, ‘I’ve got this horrible thing going on in my life,’ and had the other person walk away. That’s not how human beings work.

Even though there’s a voice in your head that says, ‘I can’t do this. I shouldn’t do this,’ you can and you should. It’s a must. Because if you’re not sharing that thing, it will continue to grow and have power over you. And eventually, that voice in your head will tell you something very dangerous.”