Whoever thought the 10-year-old kid carving crude tattoos of comic-book characters with a steel-tipped ink pen on the arms of his classmates at St. Vincent de Paul school would become one of America’s most successful artists? That his wasted hours in the pool halls of St. Paul would cultivate his taste for characters? That his fascination with the huge, onyx sculpture in St. Paul’s City Hall, “Indian God of Peace,” would foster his appreciation for form and oversize art?

Certainly not LeRoy Neiman’s mother, who threw away his early comic-book art because she thought “any kid could draw if he wanted to.” Not the nuns who discovered the blistered skin of his tattooed schoolmates and promised to find the culprit to give him a “thwacking he won’t forget.”

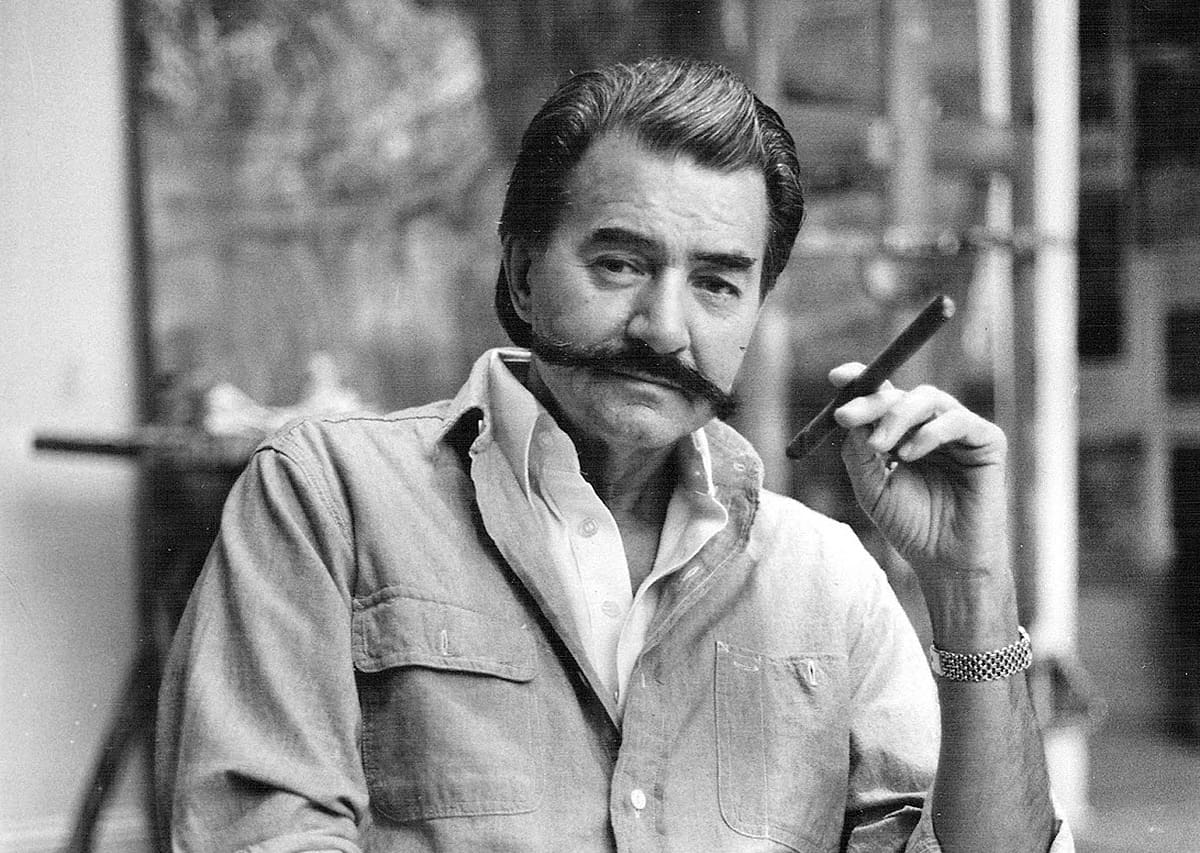

Neiman, he with the outsized mustache and the dark looks of a South American bandito, was on the road to nowhere as a kid growing up in St. Paul’s Frogtown neighborhood.

But his art saved him, and it saved him spectacularly, leading him to a long career as the chronicler of prizefights, movie stars, Olympic Games, Formula 1 races, and the international watering holes and resorts peopled by what came to be known as the world’s jet set.

“He was a very stylish guy,” remembers Twin Cities sculptor and Neiman collector Bill Mack, who often visited the artist in New York City. “He’d walk into a building, and you knew he was LeRoy Neiman. You wouldn’t know Jasper Johns if he walked in. But you knew LeRoy.”

It wasn’t just the mustache that sometimes curved all the way around his cheeks, ending within half an inch of his earlobes. There was the trademark cigar, maybe an open-collar silk shirt worn untucked. And there was that swept-back mane of hair, silver as he aged and still luxurious at his death in the summer of 2012 at age 91.

Neiman graduated from the school of hard knocks and moved into a world as vivid and splashy as the paintings that made him famous, kaleidoscopes of color and life that excited his fans even as critics dismissed him. At the end of his days, Neiman triumphed. His fortune and fame grew, and his artwork fetched higher and higher prices.

And the kid from Van Buren Avenue did it his way.

“LeRoy Neiman quite intentionally invented himself as a flamboyant artist in much the same way that I became Mr. Playboy,” Hugh Hefner once remarked.

Neiman agreed. “I guess I created LeRoy Neiman,” he said. “Nobody else told me how to do it.”

Neiman was formed in the crucible of a broken home and the streets of St. Paul. Born in Braham, he, his brother and his mother, Lydia Serline, were abandoned by his dad, a drifter named Charles Julius Runquist, a few years after Neiman’s birth. But his spirited and attractive mother, a teetotaler who won dance competitions doing the Charleston, shrugged off Runquist and moved with her two young sons to the big city of St. Paul. There, she went through two more marriages, and one of Neiman’s stepfathers, a Polish-German-American leather factory foreman, lent the artist his last name.

As a youngster, Neiman hung around with poor kids and toughs, sometimes jumping on trains to ride the rails with hobos before hitchhiking back home. During summers he worked on his grandmother’s farm in Braham.

In St. Paul, Neiman studied the portraits of former governors at the state capitol, noting the portraitists’ techniques. He walked among the mansions on Summit Avenue, though he would later write in his autobiography, All Told, “I was never envious, just curious. I had heard enough about the loveless lives of folks on the hill, but how could [their lives] be worse than ours down in gasoline alley? A lifetime later, when I saw that world up close enough to paint its brash, brassy life of conspicuous consumption, I never lost sight of what it looked like from the bottom up.”

He began climbing the ladder to the top of the art world when his sixth-grade teacher, Sister Marie de Lourdes, submitted his crayon drawing of a northern trout from Milles Lacs Lake to an art contest. It won an award, though Neiman later noted that “nobody noticed.”

But he was on his way.

As a teenager, Neiman frequented St. Paul fight clubs and began sketching boxers, a passion that would stay with him the rest of his life. When traveling carnivals came to town, he drew sword swallowers, fire-eaters and “hootchie cootchie girls.” He idolized gangsters and sought them out in the clubs carved from the sandstone cliffs along the Mississippi River.

Neiman wasn’t much for pastoral scenes — he was attracted to the outliers, to life’s grand spectacles.

He joined the Army at age 22 and worked as a cook during World War II. On D-day plus six, he stormed Omaha Beach in Normandy, France, and eventually entered Paris after the fall of the Germans. For fun, he illustrated the walls of mess halls with drawings of pretty women and romanced as many of them as he could. In 1946, Neiman returned to St. Paul and, courtesy of the GI Bill, studied briefly at the St. Paul School of Art before moving south to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Chicago was Neiman’s lucky city. In 1952, he spied an apartment building janitor carting half-empty cans of high-gloss enamel paints to the trash. Neiman asked if he could have them, and thus was born his technique of, as he put it, “dribbling, splattering, puddling and meandering [paint] like multicolored snakes” on canvas that he then spread using an artist’s palette knife and basic plastering tools.

It was the technique he used the rest of his career. He began winning awards, including a second prize for “Men, Boats and the Sea” at the Minnesota State Show in 1954; the piece was later hung at the Walker Art Center for a collectors exhibition. He’d send paintings to his mother, who would enter them in local contests and proudly collect the awards.

While doing illustrations for a major Chicago department store, Carson Pirie Scott & Co., Neiman met a copywriter who wanted to start a magazine targeted squarely at men. And so began Playboy. By the fifth issue in 1954, Neiman was illustrating pieces in Hugh Hefner’s fledgling magazine. He also met another copywriter at Carson’s: Janet Byrne, who would become his wife until his death.

Neiman and Hefner were a natural match, and the success of Playboy opened the doors of a new life. His first illustration, for a story about a jazz singer who committed suicide, won a prestigious award for art direction, and other magazine editors began assigning him work. But Hefner wanted Neiman on his team exclusively, and so began a relationship that served both men well.

Hefner decided to play to one of Neiman’s main talents: the ability to paint so quickly that he could take in a tableau — a fancy restaurant, a boxing match, a beach at St. Tropez — and render it into a painting in record time. His work managed to capture not only the setting and its occupants but also the energy and Zeitgeist of the moment: thoroughbreds straining to cross the finish line at the Kentucky Derby, the crowd at Maxim’s in Paris, the clash of pro football players, a tennis player reaching for a serve in a stadium with an audience as colorful as a patchwork quilt in the background — nothing seemed too large for Neiman to embrace in a painting.

He sketched sports and Olympic games live for ABC, NBC and CBS. For 15 years, with a seemingly unlimited expense account, Neiman contributed illustrations from around the world for Playboy’s feature “Man at His Leisure.” He created a simple sketch that became almost as iconic as the magazine’s trademarked bunny: a sexy, pixie of a woman in thigh-high stockings nicknamed a “femlin” who posed in seemingly endless forms to punctuate the magazine’s party-joke page.

Neiman’s association with Playboy was a double-edged sword. It granted him entrée to big events and brought him fame and fortune — by one estimate, more than 150,000 of his prints have been purchased with an estimated market value exceeding $400 million. He donated art frequently to charities, and his works hung in the Art Institute of Chicago, the Whitney Museum, St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art and dozens of other prestigious venues around the world. He collected honorary degrees.

But none of that endeared him to art critics. Even as the marketplace spoke — originals often fetched hundreds of thousands of dollars — critics didn’t relent.

Asked to share his thoughts on Neiman’s works, New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer remarked, “That might be difficult — I never think of him.”

Upon Neiman’s death, the Times labeled him an “archetypal hack” whose popularity stemmed from “his ambitiously opportunistic personality and his position as Hugh Hefner’s court artist. … With his ever-present cigar and enormous mustache, he was a cliché of the bon vivant and a bad artist in every way.”

Neiman professed not to care about his toughest critics, though he hardly ignored the art establishment. He founded (and reportedly endowed with $6 million) the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies at Columbia University in 1996. A year before his death, he and his wife donated $5 million to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to build a new student center. He’d not only studied there, but he’d also taught there for a decade before and during his Playboy years.

“I started collecting his art in the ’80s when I met him,” recalls Mack, who works from his Edina studio, Erin Taylor Editions, along with his wife, who runs an adjoining gallery, the Griffin Gallery of Fine Art. “I’ve seen him draw at fights. I’ve seen videos of him drawing. When he paints, it’s spontaneous. To capture a moment in a public place — just think of the pressure.”

“In my opinion, LeRoy is underrated,” he adds. “It’s like Picasso. They said his work will never be worth anything because there’s so much of it. You could buy a Picasso in the ’70s for a few thousand dollars. I have a LeRoy Neiman piece that was worth several thousand dollars in the ’80s and is worth half a million now. It’s a big oil painting done in the ’60s of a jazz player with a saxophone. It’s hanging in my house, and I’ll never sell it.”

When Neiman married Byrne in 1957, they returned to visit his mother in St. Paul. Then the newlyweds drove north to Duluth to find his father; they found him in a ramshackle Two Harbors boarding house living with a mangy dog. It was the last time the two would meet.

Neiman’s relations with his titular hometown weren’t much warmer, though he sometimes returned to visit. In 1985, for example, he did a painting of St. Paul’s Winter Carnival.

Twelve years later, as Neiman was negotiating with St. Paul to contribute $4.5 million to fund a downtown museum that would display much of his artwork, Pioneer Press columnist Katherine Lanpher decreed that his art “stinks” and compared it to “Precious Moments figurines and ceramic villages of Little Dickensian houses.”

Neiman said he felt as if he’d been “mugged” by a cabal of “uptight citizens who couldn’t justify matching me up with their Saintly City. It was the Playboy artist stigma again, but I was over it. That was the last time I let St. Paul put me on a roasting spit.”

A peacemaking expedition to Manhattan by Minnesota Gov. Arne Carlson and St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman couldn’t convince the artist to change his mind.

Neiman’s extravagant mustache was suggested by Salvador Dalí’s wife, Gala, whose advice could have applied to his art and marketing genius as well as his facial hair.

“LeRoy,” she said, “never do anything in half measures. Either grow your mustache wider like Salvador and make it a character or cut it to mouth width like Omar Sharif.”

He went long; he wasn’t a half-measure artist. Whether it was his mustache, his portraits of baseball players on Wheaties boxes, sketches of delicate Kirov dancers or an oversize painting on the fuselage of a Manhattan radio station’s traffic helicopter, Neiman splashed it out.

“I’m a painter of imaginary people and places,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Don’t mean they weren’t there, it’s just they weren’t there quite the way I painted them. … Painting is making invisible things visible.”

For Neiman, painting was also his passport out of the tough streets and bars of St. Paul and into the pantheon of modern American painters alongside the likes of Andrew Wyeth and Peter Max. For him, revenge was a dish best served in bright colors.

Oh, Jesse, Where Art Thou?

In 1999, former Washington correspondent for the St. Paul Dispatch/Pioneer Press Albert Eisele invited his friend LeRoy Neiman to attend a speech by then-governor Jesse Venture at DC’s National Press Club. While there, Neiman drew sketches of the wrestler-turned-politician that he turned into a 4-foot-by-5-foot impressionistic portrait. Neiman offered the painting to Ventura to use as his official portrait at the state capitol. Ventura declined, and to this day, Eisele wonders what became of the artwork.

Reproductions of the painting of Ventura giving Winston Churchill’s classic “V for Victory” sign aren’t hard to find. As recently as late October, a “framed bookplate image” of the piece was offered for sale on eBay for $40, and the painting is searchable online.

The final say? According to Tara Zabor, director of operations with the LeRoy Neiman Foundation in New York City, the painting is owned by the artist’s foundation.