Once a year, stunned vacationers at the upscale Arizona Biltmore find their posh summer retreat invaded by hordes of scantily clad, tattoo-laden guests. Hundreds of artists and enthusiasts descend upon the Phoenix hotel for the Hell City Tattoo Festival, a sort of mecca for lovers of body modification. These deeply devoted fans, or “Hellions,” as they call themselves, can get fresh ink, watch their favorite artists in action and even show off their own tats to win prizes.

This year, a virgin-skinned writer from Minnesota joined the throng. I trotted through the doors of Hell City wearing cheerful nautical stripes and embroidered flamingo espadrilles — an outfit that had seemed like a better idea back in the confines of my hotel room. My fellow convention-goers, adorned in head-to-toe tattoos, gauge earrings and the like, were braving the sweltering summer heat to smoke cigarettes and weed outside the building, creating a pseudo gauntlet that I awkwardly ducked through. I tried to casually nod as if I, too, were in the know and that my stripes were hiding some badass barbed-wire tattoo. In return, all I got were a few stony glares and a puff of sweet-smelling smoke blown in my face.

Why was I even at this rowdy convention? To dig into this billion-dollar industry. Hell City in particular is legendary for its raucous traditions, including freak shows and live burlesque. During the day, busty women are ogled on stage as they compete for the coveted honor of being named the No. 1 hottie in the Hell City Hotties pageant. Come night, pool parties offer the perfect opportunity to display new ink in skimpy bikinis. This crowd’s passion is permanently modifying their bodies and having a damn good time doing it.

Little do I know, beefcake is just the beginning. At least Big Greg’s tattoo is intentional; I meet dozens of Hellions who have alcohol-induced ink and no memory of receiving it. Shockingly questionable tats (and explanations) are a dime a dozen. Ohio artist Nathan Varney explains very seriously that his tattoo of a waffle is an homage to his grandmother, who used to make him — you guessed it — waffles. Several artists show me tattoos of burning crosses they got as “a fuck you to religion.”

And yet I also meet many Hellions who have deeply personal, meaningful reasons for each piece of artwork on their bodies. One attendee’s grandfather received an arm sleeve to commemorate his World War II service; he has come to Hell City to put that same tattoo on his arm. Some attendees want the handwriting of a deceased loved one placed on their bodies as a sort of physical memorial.

Stories of redemption and hope are everywhere. One of the most popular Hellions is an armless man receiving a full-color octopus tattoo over his chest and back, with an arm being inked onto the stub of his own arm. “When I was 10, I touched a power line, and it blew out a breaker at 62,000 volts,” he explains. “I lost my arm and most of my toes, and my feet are scarred. My tattoos represent ways that my family and I are survivors. Today, we’re finishing this octopus, because when you cut off an octopus’s arm, it grows back.”

These days, tattoos are considered socially acceptable, if not mainstream; nearly 29% of Americans had tattoos in 2016. But that saturation wasn’t always the case. Until the late eighties and early nineties, tattoos were often an unspoken sign of a long-term prison sentence. Still today they have that same association, and for good reason: Tattoos remain an incarceration rite of passage.

Some tattoos are more common than others. In a sample of 100,000 prisoners, The Economist found 117 inmates with a variation of the phrase “Mother Tried,” 31 with “Fuck the Police,” and seven with “Your Name” on their penises. The most frequent crime-related tattoos have their own lexicon. A watch with no hands indicates a life sentence, signifying time standing still. An outline of a teardrop implies that a murder is coming, and if the murder is successful, the teardrop is filled in.

In Russia, where the government tattooed prisoners until 1863 and 95% of high-security convicts are tattooed today, an incredibly complex code language operates. Playing cards, for instance, have specific meanings, with spades representing a thief, diamonds indicating an informant and hearts signaling someone seeking romance. Some inmates have churches on their backs or chests, with cupolas marking the number of convictions and bells signifying a conviction without parole. Pedophiles reportedly receive mermaids on their stomachs, and murders often get skull tattoos.

I ask Hellion Jordan Bender if he’s ever been stereotyped as a con thanks to his face and neck tattoos. He nods: “You get all sorts of weird reactions. Some people get scared at the sight of me. I remodel homes, and my company has to call clients beforehand to warn them that I’m fully tattooed and tell them I’m not actually a felon.”

“All this horseshit stuff, like script on people’s foreheads — I don’t care who does it, you look like you just got out of prison,” adds celebrity tattoo artist Josh Payne. That transgressive quality, however, seems to be part of the allure for a rising number of millennials eagerly sporting face tattoos. Younger generations see them as a commitment to achieving success in a creative field. When The New York Times interviewed 30-year-old creative director Travis Hardy, he noted that his face tattoo was a permanent mark of his desire to avoid corporate culture: “There’s no turning back. There’s no normal job or whatever. I’m going to continue to creative direct or write treatments for music videos or stage design. I’m not going to turn around. This served as a stamp: I believe in myself.”

At Hell City, face tats are considered a universally bad idea, but they’re by no means the worst tattoos these people have ever seen. Big Greg and his partner, [Big] Jeff, laugh uproariously at their favorite horrible tattoo, even showing me photos on their phones. It’s a man’s torso with a life-size tattoo of his internal organs and intestines, with feces making its way to the colon. A banner exclaiming “This, Too, Shall Pass” waves proudly above it.

Some of the bad tattoos are lighthearted, while others are just disturbing. One artist tells me about a man who came into his shop requesting tattoos of his stillborn baby’s footprints crawling over his torso.

Other artists have had to correct mistakes. One tells me of a client who came in to have his face tattoo fixed; he had requested “Chief” but had gotten “Cheif.” Some Hellions are too afraid to tell me about their tattoos for fear their relatives might read Artful Living.

This application and removal may sound simple, but in truth, it can be outrageously expensive. These days, acclaimed tattoo artists charge between $100 and $500 an hour, and that’s once you can get off their waitlist. Celebrity artist Scott Campbell, whose clientele includes Penelope Cruz, Josh Hartnett, Marc Jacobs, Courtney Love and Kanye West, charges $2,000 an hour.

At New York City’s Bang Bang tattoo shop, junior artists complete black and gray arm sleeves for prices nearing $20,000. The shop recently underwent a $1-million renovation and now boasts a koi pond, fridges filled with Fiji water, and video screens displaying content from the shop’s full-time videographer. “It’s like the Apple Store in here,” Miley Cyrus told The New York Times when she showed up for some new tats (her mom’s signature on her arm and an impromptu ankle tattoo displaying “slang for part of the female genitalia”).

Acclaim often comes from tattooing movie stars and rock stars, as was the case for Bang Bang owner Keith McCurdy. He achieved international fame after tattooing Rihanna and today is sought out by well-to-do clients from around the world. His shop tattoos a mile-long list of the rich and famous, including Orlando Bloom, Nicolas Cage, Katy Perry, and Kylie and Kendall Jenner. Justin Bieber, meanwhile, will fly McCurdy across the globe when he wants a tattoo; the artist traveled to Panama on a moment’s notice for a reported $10,000 to give the pop star some fresh ink. For his part, McCurdy owns Amazon stock, plans to launch a Netflix show about Bang Bang and just purchased an entirely new set of teeth.

Technology has transformed the industry, with tools and materials at a premium. In 2018, VICE followed rapper 2 Chainz’s quest to find the most expensive tattoo in the world. He settled on Hart & Huntington Tattoo Co. in Las Vegas, owned by freestyle motorcyclist Carey Hart who’s equally well known for being singer Pink’s husband and being the first motorcyclist to ever do a backflip. Although the tattoo was small, the ink alone cost a reported $9,000 per bottle — and only 10 bottles existed. It was made from exhaust carbon ash and smoldering tire remains collected from tracks left by Hart’s own motorcycle.

But for those who don’t require the royal treatment, tattoos remain a relatively accessible form of art. By the end of the Hell City convention, I find myself chatting and laughing with everyone from Vietnamese gang members to middle-class parents, each with an interesting story to tell.

I escape without too many questions as to why I don’t have tattoos myself — that is, until the last day. I’m cornered by two of my new artist friends, Sean and Nathan, who are dead set on making a sacrifice to the tattoo gods (i.e. tattooing virgin skin). I stutter and stammer. To tell the truth? I finally understand the appeal of an instantaneous yet permanent declaration of yourself on your own skin. I escape only by promising that I’ll be back to get inked.

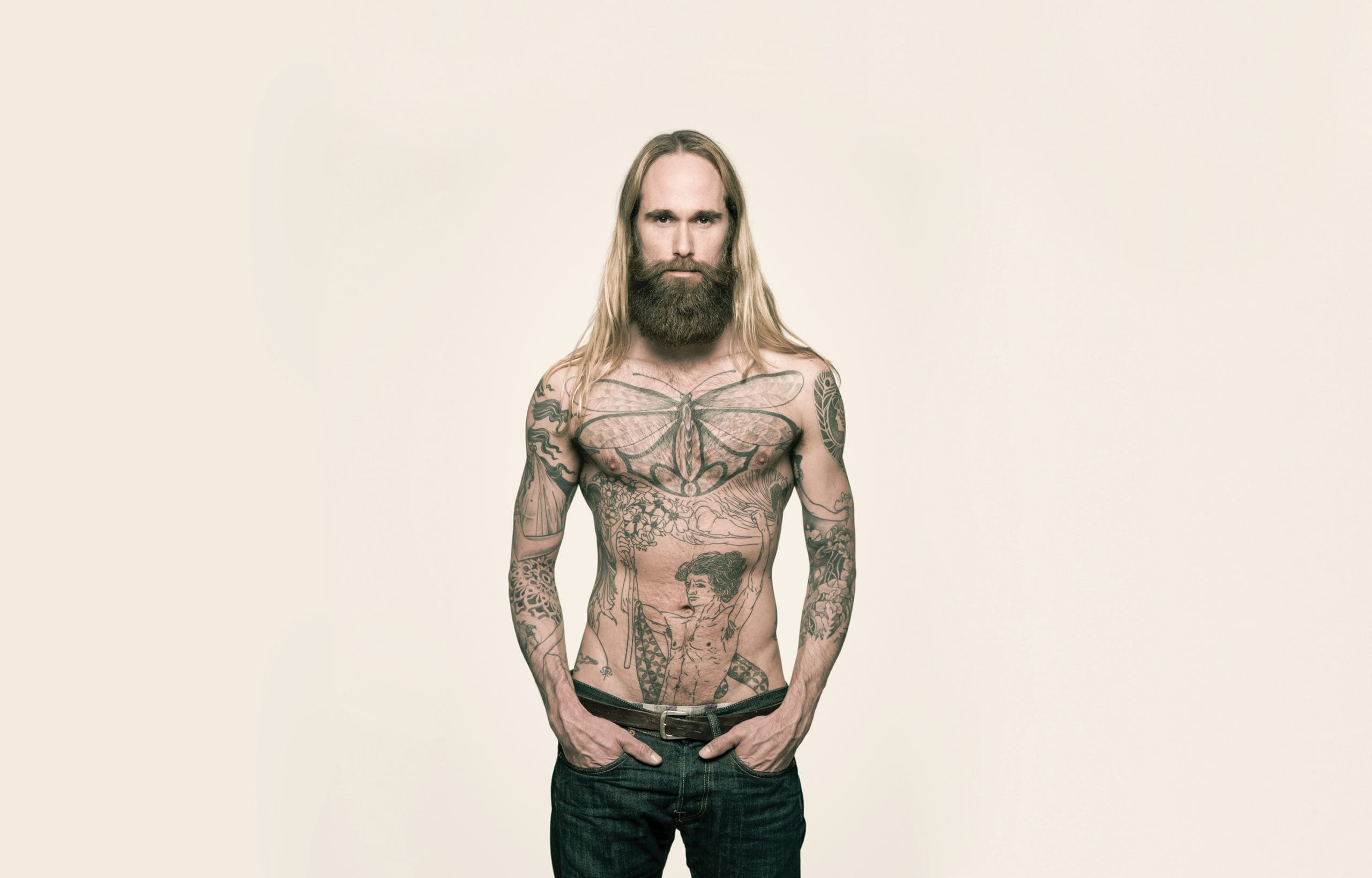

Ralf Mitsch’s book Why I Love Tattoos features 50+ portraits of people who share the inspiration behind their ink.