Forty years ago, an elderly, ailing Duluth heiress was smothered in her bed with a satin pillow and her nurse bludgeoned to death with a candlestick holder on a sweeping staircase overlooking Lake Superior.

It began in the early morning hours of June 27, 1977, when an unassuming killer lurked in the tiny cemetery bordering the mansion grounds. Pacing amongst the headstones, he shivered and his hands shook, whether from the lake breeze or the nips he was sneaking from the pint of vodka in his pocket.

His mission: break into the 39-room mansion and solve his massive financial problems. But was he alone there in the dark? Did he intend to commit murder or was robbery the idea? And most importantly, who planned the crime?

These unanswered questions — along with the brutality of the attacks and the wide-ranging aftermath that includes arson, bigamy and more dead bodies — keep the buzz about this murder mystery alive today. There are books about the case, television docudramas, even a musical. Adding to the fascination: the scene of the crime, the historic Glensheen mansion, is open for public tours.

The killer’s cemetery vigil ended that night when Elisabeth Congdon, one of Minnesota’s wealthiest women, drifted off to sleep and the night nurse turned off the lights. Around 2 a.m., he stumbled onward.

His name was Roger Caldwell, and he was an out-of-work salesman from Golden, Colorado. Two years earlier, he’d married Marjorie LeRoy, a middle-aged divorcée with seven children. Roger later claimed he didn’t realize it when they met, but Marjorie wasn’t your typical Minnesota transplant. She was Marjorie Congdon, one of the Duluth Congdons, granddaughter of Chester, the mining magnate who made a fortune in iron ore, served in the legislature and built the mansion on the lake at the turn of the 20th century.

Chester’s youngest daughter, Elisabeth had never married. In the 1930s, she adopted two infants and raised them in the grandeur of Glensheen. The girls weren’t particularly close growing up, but to please their mother, they were maids of honor in each other’s weddings. Jennifer and her husband moved to Wisconsin. Marjorie married an accountant and lived in Minneapolis. That marriage lasted 20 years before her frustrated husband, worn down by her overspending, filed for divorce.

Afterward, Marjorie moved to Colorado for a fresh start in the mountains. She met Roger in 1975 at a Parents Without Partners meeting. She was bubbly and vivacious; he was malleable and available. They soon married. To fund her outlandish spending sprees over the years, Marjorie had relied on the Bank of Mom and had even cleaned out her million-dollar trust fund. She bought extravagant clothing, dozens of boots and skates, and hundreds of matching outfits for her children for their horse shows and ice-skating competitions. She bounced checks, trusting her mother would eventually pay the bills. And she did. But now, with Elisabeth reeling from a stroke and needing around-the-clock nursing care, the Congdon trustees stepped in. No more, they said.

By the spring of 1977, the Colorado Caldwells were broke, their home foreclosed, their cars repossessed. And yet, they toured multimillion-dollar ranches, telling realtors that her mother would handle the purchase because the mountain air would help Marjorie’s youngest son, 17-year-old Ricky, with his asthma.

That June night, Marjorie’s mother slept in her bedroom up on the mansion’s second story. Across the hallway, night nurse Velma Pietila made her final checks. She was unaccustomed to the overnight shift; she’d been the head nurse for several years, working days and becoming close with the heiress. She’d retired a month earlier so she could play golf with her husband and enjoy her grandchildren. She agreed to fill in, this night only, when another nurse asked for the evening off and no replacement could be found. Her husband begged her not to go.

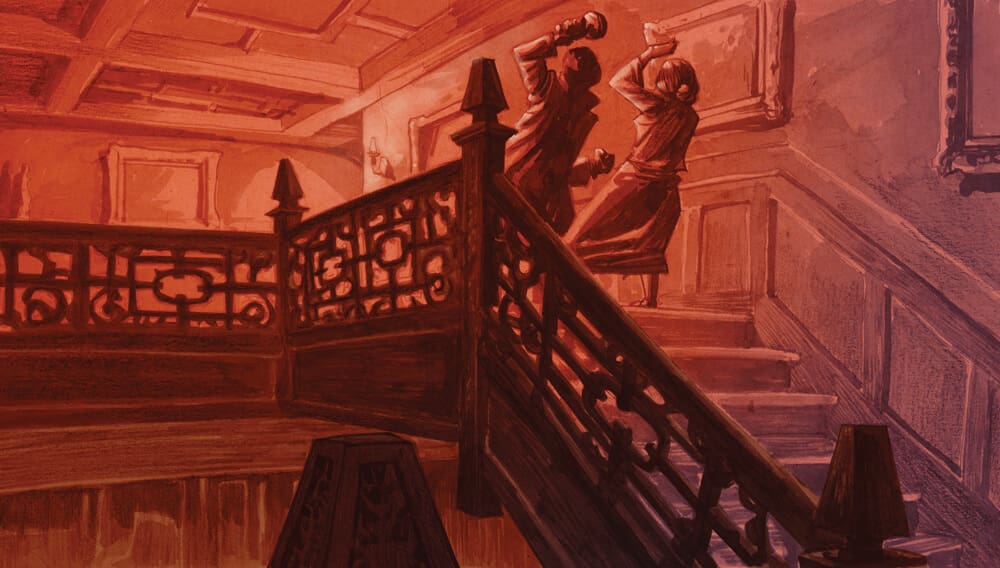

The next morning, day nurse Mildred Garvue arrived at Glensheen at 7 a.m. and was surprised to find the front door unlocked. After stopping to see the cook in the kitchen, she noticed her friend and fellow nurse lying askew on the window seat of the grand staircase. It didn’t register. Why, she wondered, was Velma taking a nap?

Approaching, Garvue saw that Pietila was beaten and bloody, clearly dead. Now terrorized, she rushed upstairs to find Elisabeth dead in her bed, a satin pillow covering her face. The room was disheveled, jewelry strewn on the floor and another pillow tossed to the side. She rushed back downstairs and called 911. The dispatcher stayed on the line in case the killer was still in the house.

Police arrived and searched the grounds. The culprit was gone. Their scenario: A broken window in the billiard room on the lowest level of the house was the entry point. In the dark, the killer had gone upstairs to the first floor then started up toward the bedroom level. Pietila heard him approach and confronted him on the landing. She fought and clawed but was soon overwhelmed by a larger force. She collapsed, but her moans grew louder, so he grabbed a brass candlestick holder and, as he later explained, “beat her with it to quiet her down.”

In the bedroom upstairs, he held a pillow over Elisabeth’s face; partially paralyzed, she was unable to fight back. When she stopped struggling, some five minutes later, he rummaged through a closet and a night table, putting some jewelry in a basket, taking Elisabeth’s diamond ring from her finger and a gold watch from her wrist, and snatching an ancient gold coin from a dresser.

Covered with the nurse’s blood, he washed his hands and face in the small bathroom across the hall, leaving a bloody residue but no fingerprints. He rummaged through the nurse’s purse, found her car keys and fled the mansion, leaving the door unlocked.

By late morning, with the scene secured, police gave their first official statement. The brutal double homicide, they said, occurred during a botched burglary. Some jewelry had been taken.

Three days later, relatives from around the country arrived in Duluth for Elisabeth’s funeral. Marjorie and Roger came in from Denver, and police noticed bruises and cuts on his face and hands. He’d been kicked by a horse, his wife told them.

![]() The botched burglary scenario remained the public version of the crime for the first week, but police were already exploring a different motive. Upon hearing of the heinous murders, several Congdon family members, long aware of Marjorie’s financial woes and vindictive nature, urged police to take a close look at Elisabeth’s daughter and her new husband.

The botched burglary scenario remained the public version of the crime for the first week, but police were already exploring a different motive. Upon hearing of the heinous murders, several Congdon family members, long aware of Marjorie’s financial woes and vindictive nature, urged police to take a close look at Elisabeth’s daughter and her new husband.

There’d been earlier scares, they reported, like the marmalade incident. At a family gathering a few years earlier, Elisabeth had become quite ill. Someone remembered that Marjorie had fed her some homemade orange marmalade. Tests showed the presence of a dangerous chemical in Elisabeth’s blood, but the marmalade jar was never found and authorities were not notified.

Now, in the wake of the murders, such details were important to the Duluth police as they dug into their biggest homicide case ever. Diligent, sometimes sloppy forensic work continued at the mansion for days. Blood and hair were cataloged, but no incriminating fingerprints were found. The lack of DNA technology in those days made the case all the more difficult for the prosecution.

Yet a trail of evidence began to emerge. There was the handwritten will, dated three days before the murders, in which Marjorie signed over to Roger a $2.5-million portion of her expected $8-million inheritance.

Then there was the fact that Roger had flown to Duluth a month earlier to ask Elisabeth and the family trustees for $750,000 to buy a ranch. At the very least, he told them, he and Marjorie needed $500,000 to pay off debts and stay out of jail. His request was refused.

Furthermore there was the envelope, addressed to Mr. Roger Caldwell, in what appeared to be his own handwriting, found in the Caldwells’ Colorado mailbox (it arrived after they’d left for the funeral). Inside was a Byzantine-era coin, like the one taken from Elisabeth’s bedroom. An expert said a thumbprint on the envelope matched Roger’s. And it had been postmarked in Duluth the day of the murders.

Hair found at the scene “closely matched” Roger’s, and some of the blood found matched his blood type.

Jewelry found in the Caldwells’ hotel room after the funeral was strikingly similar to that taken from the mansion. Upon questioning, Marjorie told police the baubles belonged to her and that she and her mother owned many identical items.

The nurse’s car was discovered at the Minneapolis–St. Paul airport the day after the murder. In a garbage can, maintenance workers found the keys and a parking ticket with a time stamp of 6:35 a.m., enough time for the killer to make the 150-mile drive from Duluth after the crime. While searching the Caldwells’ room, police found a receipt from an MSP airport gift shop for a suit bag bought the morning of the murders. Roger had such a bag. Shown a picture of him, two gift-shop workers thought he might have been the buyer.

There was no smoking gun, but chief prosecutor John DeSanto and his team felt their case was strong. Upon hearing that the Minneapolis newspaper planned to publish a story on the Colorado connection, they arrested Roger two weeks after the homicides.

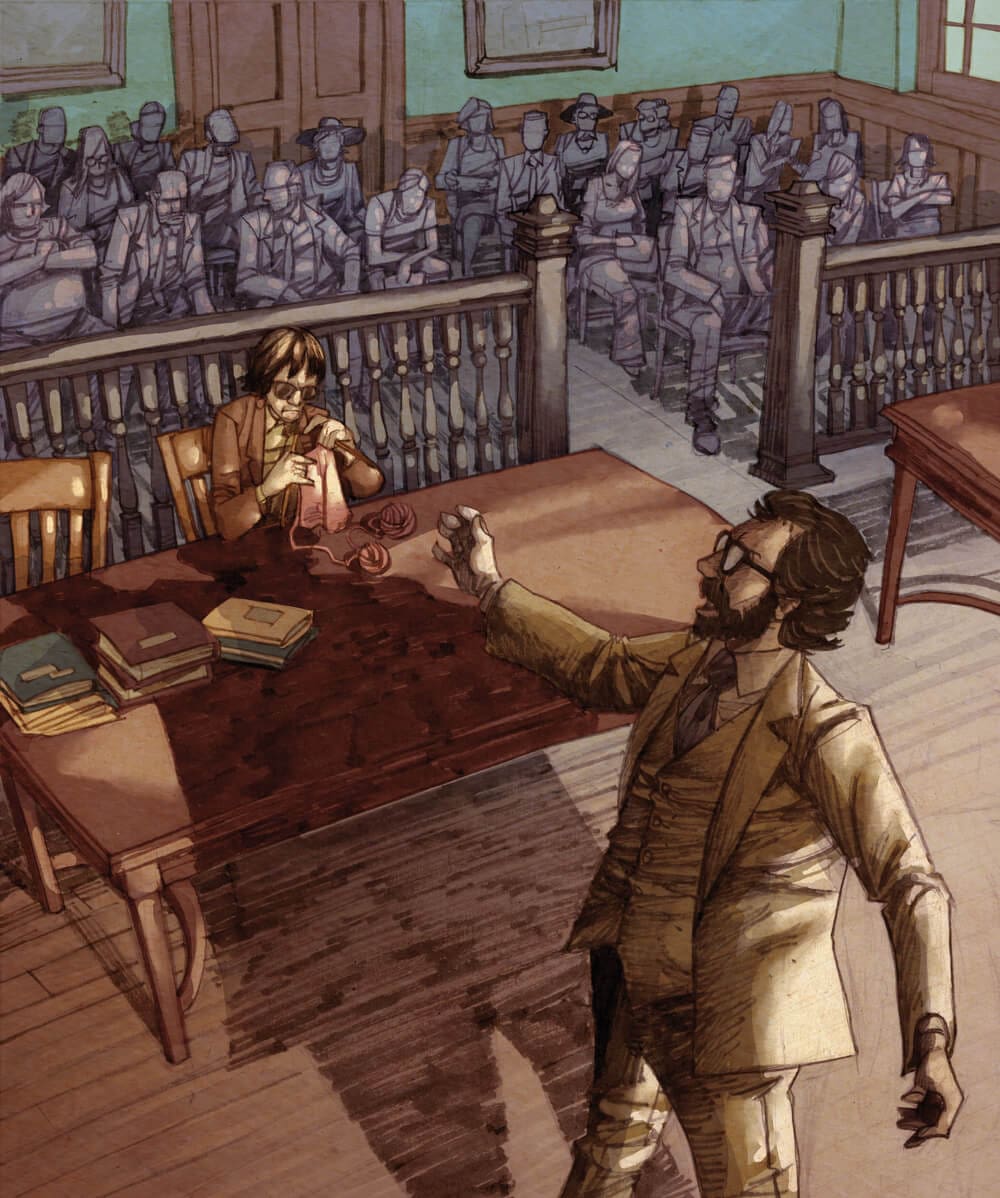

![]() Roger’s lawyers worried about getting a fair trial in Duluth, which has an indisputable Congdon legacy; there’s a Congdon Boulevard, a Congdon Park and a Congdon school. A judge agreed to move the proceedings to Brainerd.

Roger’s lawyers worried about getting a fair trial in Duluth, which has an indisputable Congdon legacy; there’s a Congdon Boulevard, a Congdon Park and a Congdon school. A judge agreed to move the proceedings to Brainerd.

Jury selection began in April 1978, ten months after the murders. It took more than three weeks to find 12 citizens to hear the case. Testimony started May 9 with lead investigator Sergeant Gary Waller showing gruesome pictures of the crime scene and taking jurors through the evidence.

A hole in the case arose when police couldn’t identify two handprints found in the bathroom where the killer had washed up. They didn’t match Roger’s prints, so the defense grandly argued that they belonged to the “real killer.” To clear things up, police went back to the lab to reexamine the evidence. Later in the trial, they admitted they’d solved the mystery: One print belonged to a Congdon nurse; the other was Waller’s, left in the sink early in the investigation.

Another disruption was the abrupt dismissal of a juror. Eventually it came out she’d received an unsigned letter offering $10,000 for a guilty verdict. The judge ruled that she couldn’t be fair under the circumstances. No one was ever charged with sending the letter.

Among the other quandaries: No one had seen Roger in Duluth that day, and despite extensive efforts, police couldn’t place him on any airline passenger list for flights from Denver to Minneapolis and back again (airport security wasn’t as tight back in 1977).

There was also no clear explanation as to why Roger would mail himself the stolen gold coin. He had returned to Denver long before it arrived, so it seemed unlikely to be a message to Marjorie that the deed was done. The defense claimed the envelope was part of an elaborate frame-up.

The nurse’s stolen car was a quagmire. Pietila was filling in that night and left her car by the front door, but other night nurses didn’t always drive to work. The killer apparently found her keys and drove her car to the airport. Wouldn’t someone planning a murder have a better getaway plan?

And in a theatrical ploy, the defense demonstrated that Roger’s arm wouldn’t have fit through the shards of glass in the broken basement window that the killer used for entry. Employing a cardboard mockup of the window, Roger’s attorney had a testifying police officer reach through as if to unlatch a lock on the other side. The officer’s arm, which was thinner than Roger’s, couldn’t fit through the opening without dislodging simulated glass fragments.

Roger didn’t testify during his trial. After eight weeks of testimony, more than 500 pieces of evidence and 109 witnesses, the jurors got the case. They deliberated for two and a half days before declaring him guilty of both murders. Roger was sentenced to two consecutive life terms in prison, with a minimum of 35 years behind bars. But in another twist, he would serve far, far less time.

![]() Roger’s conviction gave DeSanto and the prosecution team the confidence to go further. The day after his sentencing, they charged Marjorie with planning the murders.

Roger’s conviction gave DeSanto and the prosecution team the confidence to go further. The day after his sentencing, they charged Marjorie with planning the murders.

It was a circumstantial case of conspiracy. No one alleged that she had physically committed the murders, as many witnesses had seen her in Colorado, more than 800 miles away. But, the theory went, Roger would not have undertaken the crime on his own. He didn’t know his way around Duluth or the mansion. He lacked ambition, he was easily persuaded and he liked to drink. And in the hours and days after the murders, Marjorie had given inconsistent statements as to why Roger was not seen in Colorado during the crucial time period.

Marjorie hired Minneapolis attorney Ron Meshbesher, the top defense lawyer in the region who was well-known for some highly publicized acquittals. He had the advantage of knowing exactly what evidence the prosecution would use against his client as he had the transcript from Roger’s trial. On top of that, he had an additional 10 months to find holes in the case that could show reasonable doubt.

Marjorie’s trial was moved to Hastings. Two major developments arose during testimony: Meshbesher found an expert who disputed the crucial fingerprint on the envelope with the stolen gold coin, the key link placing Roger in Duluth the day of the murders.

And defense investigators went back to Colorado and found a waitress who now, nearly two years after the crime, changed her story and suddenly remembered seeing Roger that day. In earlier interviews with police, she’d never mentioned his presence, but she came to Hastings and told the jury he was there.

Another major difference in the trials? Marjorie herself. She knitted at the defense table, openly smiled at jurors and kept a book nearby. She even brought a cake to the courtroom for Meshbesher’s birthday, chatting with reporters and spectators during breaks. She didn’t look like a conniving plotter.

Initially, Marjorie insisted on testifying, but she eventually agreed it would be best to remain silent. Her team instead attacked the evidence used to convict Roger. The message to the jurors: The couple had been framed, or at the very least, Roger had done it on his own.

After six weeks of testimony, the jury deliberated for 10 hours and found Marjorie not guilty. After the verdict was read, some of the jurors came forward, hugging the defendant and congratulating her.

Though disappointed and certain that the defense’s theories were false, the prosecutors consoled themselves knowing they had the actual killer in prison. But even that comfort wouldn’t last.

![]() Based on Marjorie’s acquittal, Roger’s attorneys filed an appeal. Without the incriminating fingerprint, they were sure they would prevail in a second trial. (The Colorado waitress had by now recanted her claim of seeing Roger, but it was too late for Marjorie’s case.)

Based on Marjorie’s acquittal, Roger’s attorneys filed an appeal. Without the incriminating fingerprint, they were sure they would prevail in a second trial. (The Colorado waitress had by now recanted her claim of seeing Roger, but it was too late for Marjorie’s case.)

The appeal process grinded slowly ahead, and in August 1982, the Minnesota Supreme Court overturned Roger’s conviction and ordered a new trial. He was released, having served more than five years.

Back in Duluth, authorities were in a bind. A new trial, after all those years, would be problematic. In addition to the new evidence from Marjorie’s trial, witnesses had died. Plus the cost of a second trial would be huge. They worried that if they lost — and Roger walked free — the city’s biggest murder case would remain unsolved.

They proposed a plea bargain. If Roger would confess, they’d offer him a much shorter sentence: just one additional year in prison.

Roger, by now living in his hometown of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, held out for better terms. Negotiations led to a new deal: guilty pleas in return for no further prison time. With that promise in hand, he quickly agreed.

Roger returned to Duluth and confessed in court, saying he’d waited outside the mansion that night, broken in and killed the women. He was drinking heavily, he said, and couldn’t remember crucial details, like how he’d flown to and from Minnesota without detection. He didn’t remember taking the gold coin from the bedroom. He showed no remorse. There was no mention of an accomplice.

His intent, he claimed, was burglary, not homicide. And he insisted there was no getaway scheme: “I didn’t have any plan,” he said in the confession. “I didn’t — this was the most amateurish, slipshod thing, now that I’ve had years to ponder it.” And even though Marjorie was legally in the clear thanks to double-jeopardy rules, Roger denied that she had any involvement or knowledge of the crime.

Free and back in Pennsylvania, Roger fared poorly. He was obese, alcoholic and on welfare. He received $186 a month, lived above a bar and wore clothes from the Salvation Army.

At one point, he contacted the Congdons with a proposal that, if they paid him handsomely, he’d provide evidence showing that others were involved in the murders. Reluctantly, the family agreed to a sum of $50,000 but asked for proof that the evidence was sound. Roger refused and raised the price to $100,000. Negotiations broke off.

In 1988, Roger slit his wrists with a steak knife. He was 54. I was one of nine people at his funeral. Near his body, police found a suicide note, in which he claimed he “didn’t kill those girls or to my knowled [sic] ever harm a soul in my life.”

Was this deathbed disclosure truthful? Turns out Roger had a girlfriend in Latrobe, but she hadn’t attended his funeral because she was in the hospital with a broken collarbone after being badly beaten. So, in fact, he could harm a soul, particularly when drunk. The note was a lie.

![]() When Marjorie was acquitted of plotting to kill her mother, many felt she had escaped justice using a clever lawyer and taking advantage of police mistakes. But eventually, she paid a price for other misdeeds.

When Marjorie was acquitted of plotting to kill her mother, many felt she had escaped justice using a clever lawyer and taking advantage of police mistakes. But eventually, she paid a price for other misdeeds.

Marjorie visited Roger only once while he was in prison. And in 1981, she married a man named Wally Hagen in a North Dakota civil ceremony — without first divorcing Roger. Authorities filed bigamy charges against her, but because it’s not an extraditable crime, she was never arrested. Wally and Helen Hagen had known Marjorie since the 1960s, when their children performed together in ice-skating competitions. They were among the few friends who remained in touch with her. After Marjorie’s acquittal, Helen was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and placed in a nursing home. She lapsed into an unexplained coma days after arriving; nurses reported that the last person to visit her was Marjorie. Three days later, Helen died. Marjorie and Wally were soon inseparable.

After their wedding, a house they had just sold in the Twin Cities was set on fire the night they moved out. Marjorie, who still owed money on the mortgage, was charged with arson. Investigators uncovered a series of unexplained fires in her background, going back to her youth. Again, Ron Meshbesher defended her. This time, they lost. She was convicted of arson and insurance fraud, and sentenced to time at the Shakopee women’s prison.

When she was released some 20 months later, she and Wally moved to the Southwest in an RV, eventually settling in tiny Ajo, Arizona, not far from the Mexican border. Wally had cancer, Marjorie told neighbors, so the couple often went to Mexico to buy his cancer drugs. It wasn’t long before a series of fires occurred in empty homes and garages across the former copper-mining town. Police suspected juveniles.

The Hagens feuded with a next-door neighbor, claiming he threw garbage into their yard and agitated their dog. One night, the neighbor, a border-patrol officer, heard a fuss at his window and found a kerosene-soaked rag on the sill. He called police, who set a trap, hoping to catch the culprit. Around 1 a.m., they saw a flash and rushed out, chasing a figure down a dark alley. It was Marjorie.

She was charged with arson once again. She was jailed for eight months, unable to make bail. Wally, who’d been confined to a wheelchair, seemed to improve while she was gone. He was alert and drove around town, visiting restaurants and flirting with women. But when Marjorie was released, pending trial, Wally’s health deteriorated again. A neighbor said she was giving him pills to sleep.

Wally testified at her arson trial, arriving in the Tucson courtroom on a gurney. He said Marjorie’s arthritis was so bad she couldn’t even hold a match. Jurors later saw him walking by himself in the parking lot.

She was convicted of the attempted arson and would later plead no-contest to other arson charges. The stiff sentence: 15 years in prison, three times longer than Roger had spent behind bars after being found guilty of two murders.

At Marjorie’s sentencing, she asked the judge for one more day of freedom to take care of Wally. The judge agreed, but police suspected she might flee to Mexico. They followed her back to Ajo and sent regular patrols by the house.

The next day, an officer smelled natural gas coming from the house. He knocked. Marjorie said all was fine, that the pilot light had blown out on her stove. A few hours later, she called friends to tell them Wally was dead.

Police found a piece of hose, cut just long enough to reach from the oven to the bedroom. Prescription pills lay near Wally’s body, along with a double suicide note, saying that she’d been unjustly accused and didn’t want to go to prison and that Wally’s health meant that he couldn’t live without her. They wished to be buried together, in one casket, along with their dog. “As we have only the three of us in life, we wish to have the three of ourselves together in death,” she’d written.

Marjorie was arrested for murder. But as the deadline for calling a grand jury neared, prosecutors questioned if their evidence would hold up in court. Maybe it had been a planned double suicide; he’d gone first then she balked. The charge was dropped.

Wally’s three children wanted their father’s body returned to Minnesota to be buried next to their mother. Marjorie, from her prison cell, refused to release it. After a long, costly legal battle, a judge granted the children half his ashes; Marjorie got the other half. That’s when the Hagen family publicly wondered if she had been involved in their mother’s death, too.

Two of Wally’s children attended a 2001 parole board hearing in Phoenix, where Marjorie, clad in a bright orange jumpsuit, was seeking early release. She took no responsibility for her actions and ranted to the board about how the Hagen children and I had caused her much trouble over the years. Several of her children had written letters to the board opposing early release. The ruling: no early parole.

In 2004, having served a decade in prison, Marjorie moved to Tucson. Shortly after her release, her lawyer, Ed Bolding, called me to say she was broke and wanted to write a book to make big money. Would I help? No, I explained. There wouldn’t be any big money or even a book deal if she wasn’t more forthcoming about her role in the murders. I also mentioned it was probably not a good idea to go into business with Marjorie.

Within a year, I learned that Marjorie had accused that attorney of stealing her money while she was in prison. Court records show that she receives about $4,800 a month from the Congdon estate and Wally’s pension, so there should have been a large accumulation waiting for her upon release.

I scoffed at the idea that someone had scammed Marjorie; throughout her life, it’s always been Marjorie who’s done the scamming. But I was wrong. Bolding was convicted of embezzling $1 million from her and another client.

In 2007, Marjorie befriended a man named Roger Sammis in an assisted-living home and offered to help with his finances. He soon died, but she kept writing checks — to herself. Police tried to determine his cause of death but learned that Marjorie had used her power of attorney to have him cremated. She was charged with fraud and forgery, and sentenced to intensive probation.

Three years later, Marjorie went to court to try to get out of her probation so she could move into an assisted-living facility. The judge denied her request.

Marjorie turns 85 this July. She still lives in Tucson.

Joe Kimball first reported on the Glensheen murders back in the seventies as a rookie reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune. He is the author of the bestselling book Secrets of the Congdon Mansion.

Read this article as it appears in the magazine.