Marjorie Congdon is a chatterbox. Or at least she was, 33 years ago. During her murder trial in Hastings in 1979, Congdon held a kind of court of her own. During breaks in the criminal proceedings, clusters of reporters formed half-moons around her as she spun stories about her mother, about growing up in Duluth’s famous mansion, even about her favorite serialized cartoon, Hägar the Horrible. She accused the Duluth police of heartlessly pulling hairs out of her husband’s armpits for evidence. She railed against his jailers for not allowing him to have a pair of Hanes underwear on which she had written “I Love You.” She also blasted the Chester Congdon estate managers for leaving her penniless and on the cliff’s edge of public assistance.

All of this ended up in print, which drove her lawyer, Ron Meshbesher, up the wall. He told her again and again not to talk to the press, but Marjorie seemed unable to help herself. She was even chatty with the prosecution, the very people trying to put her away for murder. She brought a homemade chocolate cake to court. She amiably hit up the prosecuting attorneys for donations to a horse sanctuary. (This last move brought on a stern warning from the judge that she was in court to stand trial for murder, not to solicit donations for pet causes.)

But then, on July 20, 1979, Marjorie was acquitted of conspiring to kill her mother, the fabulously wealthy Duluth mining heiress Elisabeth Congdon. Marjorie refused all questions at the courthouse and slipped into her lawyer’s gray Cadillac Seville. A few days after the trial, a reporter asked her how she celebrated her legal victory. She revealed that she bought a bag of White Castle hamburgers and enjoyed them at Como Park in St. Paul. It would be the last time she would directly answer a reporter’s question.

Joe Kimball, the former Star Tribune reporter and current MinnPost writer, holds the title for most Marjorie Congdon interview attempts. After years of making phone calls and sending certified letters to her home and to prison, he flew to Arizona in February 2001 to see her stand for parole. By then, Marjorie had served eight years in prison for attempting to burn down a house with a person inside. (Marjorie’s various biographers, including Kimball and Sharon Darby Hendry, believe she has committed dozens of arsons in her life, but she’s only been convicted of two.) At the hearing, Kimball watched her rant to the parole board about the children of her third husband, Wally Hagen. She said her ungrateful stepchildren refused to pay for her husband’s desperately needed medical care. This unforgivable neglect, in turn, forced her to commit arson and insurance fraud. Kimball watched all this in a cement-block parole room, but he didn’t get his interview.

Then, in 2005, when Marjorie was out of prison, he got a call from her lawyer that she wanted, finally, to do a tell-all book because she needed money. Kimball felt compelled to tell the truth: that there probably wouldn’t be some big payday from a book, even if she revealed all kinds of titillating information about the famous murders at Glensheen and the arsons that followed. “I told him, ‘Marjorie isn’t O.J. Simpson,’” remembers Kimball. With that, Kimball says, Marjorie shut the door on the book idea and hasn’t opened it since.

Author Sharon Darby Hendry, who wrote Glensheen’s Daughter: The Marjorie Congdon Story, made one attempt to talk to the heroine of her true-crime tale. She went to the prison in Goodyear, Ariz., where she asked the warden to ask Marjorie for an interview. “The warden told me I was crazy for wanting to talk to her,” says Hendry. “And when she came back, she said that Marjorie had gone ape over me being at the prison.”

Gail Feichtinger, the ex-Duluth News Tribune reporter and author of Will to Murder, has the best interview-attempt story, full of the kind of theatrics that make Marjorie so darkly irresistible to reporters. Feichtinger was there in 2004 when Marjorie emerged from the prison gates with a cardboard banker’s box of possessions. Feichtinger’s photographer fired off a few shots of the 71-year-old before Marjorie climbed into a hired Crown Victoria and laid down in the backseat. Feverish with excitement, reporters and TV crews tried to pursue the car, but the driver — going faster than 100 mph — zipped past a slew of vehicles on the shoulder and blurred out of sight.

I arrived in Phoenix on a bone-dry Friday evening, and considered, not for the first time, why older people choose to live in such hot climates. Are they really that cold? The air outside the airport felt like a smelting furnace and smelled of baked asphalt and singed leaves.

I had had so much swagger a week earlier at the Black Water Lounge in Duluth. There had been a buoyant private party at Glensheen, the same mansion where Elisabeth was asphyxiated in her bed, and her nurse, Velma Pietila, beaten to death on the stairs. Even the youthful Duluth mayor was there, munching on fruit kebabs and little cherry tomatoes stuffed with mozzarella. Later, at the Black Water, Artful Living’s up-for-anything publisher, Frank Roffers, yelled over the din to challenge me to go to Tucson, to find Marjorie. I hoisted my martini like a royal mace and proclaimed — loudly — that I would go anywhere for the chance to meet face-to-face with the infamous Marjorie Congdon. I was flushed and bold, the one kid at the slumber party who actually gets naked and races to the mailbox and back. Sure, I would go to Arizona to find Marjorie Congdon, the woman who many people believe is a cold-hearted killer and a real-life psychopath. Double-dog dare me.

But in the charred Arizona heat — and without my martini — the whole thing didn’t seem like quite such a good idea. For one thing, Marjorie had been diagnosed a psychopath, and at the world-renowned Menninger Clinic no less. Her second husband had slit his wrists with a steak knife. Her third husband had died suddenly of gas poisoning. And now I had flown to Tucson to throw rocks at the hornets’ nest.

Which is maybe why I started chattering excitedly to just about every person I ran into: the retired couple at the baggage carousel, the Enterprise Rent-A-Car lot attendant, even the highway patrolman who pulled me over halfway between Phoenix and Tucson on I-10 for driving at night with my headlights off and my sunglasses on.

“She’s in prison, right?” the cop said, ripping my warning off his pad and handing it back with my driver’s license. “No,” I said. “I think that’s why I’m telling you.”

On Saturday morning, I woke early and drove my rented Kia Soul right into Coronado Place, the sagging, outdated condo development where Marjorie has lived for the past eight years, since getting out of prison. I found her musty rose-colored building, and then her parking spot. Under her unit number sat a tired Chevy S-10 truck, the bed loaded down with 10-gallon plastic buckets and strange valves and tubes. My first horrified reaction was that Marjorie had graduated from arson to bomb making.

Just as I was at my most compromised, with my Kia nose-to-nose with the Chevy, and my body leaning way over the steering wheel to peek in the cab of the truck, Marjorie appeared from around the corner and stared hard at me, angry and angular behind her famous huge sunglasses. She was smaller than I thought she would be — almost bird-like, with violent varicose veins and dirty canvas slip-on shoes. A sharper reporter, someone like Kimball, would have jumped out of the car and said, “Marjorie?” But my heart, suddenly bound up in some kind of cardiovascular straitjacket, wouldn’t hear of it. As if by instinct, I slammed the Kia into reverse and sped at top speed through Coronado Place and back out into the anonymous safety of Tucson. As I drove, I took deep, gulping breaths. Is it lame, I wondered, to be this scared of an 80-year-old woman?

After that bizarre encounter, I parked outside the entrance to the development, donned my binoculars and watched for the next phase: Operation Charming Card. In Minneapolis, I had express-mailed a fabulously expensive letterpress card and enclosed a snapshot of myself cuddling with one of my two cats. This had been my father’s brilliant idea, and I was willing to go with it. After all, my father is such a gifted salesman that he was able to take the near-impossible task of selling encyclopedia sets door-to-door and turn it into a six-figure career. (This despite the fact he has a near-paralyzing fear of dogs.)

At noon, our plan began to unfold, right on schedule. I watched the USPS delivery man drive to Marjorie’s building, ring her bell and deliver my card to her outstretched hand. I stared at my cell phone, waiting for her breathless call. “I wasn’t going to talk to you,” I imagined her saying. “But when I got this beautiful card and saw this darling picture of you and your cat…”

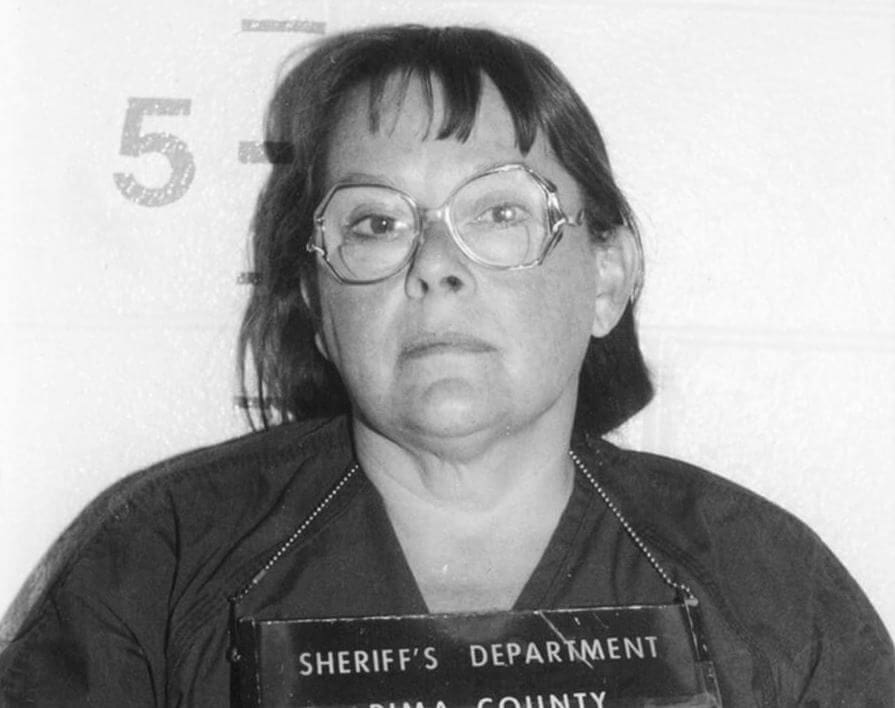

But my phone didn’t ring. For the next few hours, I went around the Coronado development, randomly ringing bells and knocking on doors, and generally being a neighborhood nuisance. No one I talked to had heard of Marjorie Caldwell, or Marjorie Hagen, or Marjorie Congdon, or Maggie Wallis, which I had read somewhere was her new nom de guerre. I accosted a middle-aged man in nurses’ scrubs who was throwing away a bag of cat droppings. I showed him Marjorie’s photo, from the cover of Glensheen’s Daughter, and his eyes flashed with recognition. “Geez, I think that’s the lady with the great big greyhound,” he said. “My lady friend lives right next door to her.”

After that, there was nothing to do but wait and watch for the Chevy S-10 to emerge from its spot. I played through the scenarios: Marjorie would drive her truck to the grocery store, and I would strike up a conversation with her in the produce section. Marjorie would drive to Denny’s, and I would amiably ask to join her in a red pleather booth and we would eat Moons Over My Hammy omelets. Marjorie would stop by the flower market, and I would delight her with a hand-tied bouquet of daisies. Marjorie would emerge from her condo wearing her big sunglasses and a white scarf, and I would surprise her by wearing the same thing, and we would snap a twinsies picture that I would post on Facebook with the caption, “Me as Marjorie Congdon with the REAL Marjorie Congdon!” After nine hours of waiting, I found, the mind gets a little silly.

Finally, at around 10 p.m., I drove the Kia back to the Holiday Inn, where I spent two demented hours Googling “psychopath” and “sociopath.” I learned, among other things, that the two words mean the same thing and that the general profile of a psychopath is a person who feels little or no empathy, who is highly intelligent, grandiose, manipulative and a pathological liar in addition to this killer ingredient: easily bored. One line, from a recent New York Times article, chilled me to my spine: “If they can get what they want without being cruel, that’s often easier. But at the end of the day, they’ll do whatever works best.”

It occurred to me that there was sad irony in the fact that a mentally ill little girl — and there’s convincing evidence that Marjorie was deeply disturbed even as a young child — would be adopted by one of the few families who had the resources to get her serious psychological treatment, but in the end chose not to. If little Jacqueline Barnes — Marjorie’s birth name — had been adopted by even a middle-class family, the burden of a psychopathic child would likely have been too great, both in resources and connections. But Marjorie was adopted by Elisabeth Congdon, a single woman so unbound by social convention that she adopted two babies all by her lonesome in the early 1930s and didn’t give two hoots what the Duluth society matrons thought about it. Though having a child who set fires and tried to poison a horse was apparently too much even for the maverick Miss Congdon, the family swept Marjorie’s “eccentricities” under the rug. That is, until the whole thing blew up in their faces.

It made me think of the formal dining room at the Glensheen mansion in Duluth, personally designed by Chester Congdon, the original patriarch. The table was designed with discreet buttons at each end, so the lord and lady of the house could summon servants without having to actually call out, “Yoo-hoo, Jeeves!” What the Congdon family needed with Marjorie — what they wanted — was a “discretion” button. They didn’t get it.

The next morning, back at my stakeout post, I stumbled into a bit of luck. A middle-aged couple pulled over next to my Kia and asked if I was part of the citywide manhunt for Isabel Celis, the 6-year-old girl who disappeared from her Tucson bedroom in April. I told them I was actually waiting for Marjorie’s white truck, because I was hoping to get an interview with her. The husband suppressed a little smile and said, “Oh Maggie doesn’t drive. Doesn’t even have a car. I think the pool guy parks in her spot.”

After some negotiation, I convinced them to let me interview them about Maggie, so long as I didn’t include their names. “We really don’t want her to get mad at us and burn our place down,” said the wife with a strange amount of cheer.

Back at their unit, the couple painted a detailed portrait of Marjorie’s post-prison life. Up until very recently, they said, her life revolved around her service dog, a rescue greyhound named Raja. On most mornings, she could be found sipping coffee with Raja in tow outside the Bruegger’s Bagels on Tanque Verde Road.

“The first time I went into her house, she opened a closet door and there were hundreds of dog leashes, in all different colors and patterns,” said the wife. “I thought it was strange because I never ever saw Raja on a leash. It was a problem, actually.”

Marjorie had apparently euthanized Raja just a few days before my trip to Arizona. “She tried everything,” said the wife, sadly. “Alternative treatments, acupuncture. I think the only time she left was to take Raja to some vet or another.”

The couple revealed that when Marjorie first moved into Coronado Place, a neighbor had slipped them a piece of notebook paper with an unfamiliar name. “Google it,” was all the neighbor had said. “That’s how the information about Marjorie gets trafficked around here,” confided the wife. “The books — Will to Murder, Glensheen’s Daughter — they get passed around.”

The couple revealed that there’s a small group of Coronado Place residents, led by the homeowner’s association president, who are “petrified” of Marjorie and document her every move in the development. (I called this association president, a woman named Mary True, and indeed she said she had compiled a “four-inch-thick binder on [Marjorie].” True refused to say more, but added, “I definitely have enough information to put her back in jail, if it comes to that.”)

Marjorie also has a few close friends, who take her grocery shopping and drink coffee with her at Bruegger’s Bagels.

I asked the couple if Marjorie ever hinted about her past. “Oh never,” said the wife. “I don’t think I’ve ever even heard her say her last name. She’s chatty, though. She likes to talk about the news — and dogs. Anything about dogs.”

When I met Marjorie’s best friend, she was watching Chopped All Stars: Judge Remix. Chef Marcus Samuelsson had just won the $50,000 grand prize and was hopping excitedly across the screen. “Oh good,” she clapped. “I wanted him to win.”

A larger, older woman in a motorized wheelchair, the friend asked that her name not be published, for fear of attracting the kind of attention that regularly annoys her infamous friend. Under those constraints, she agreed to chat for a bit. She revealed that before Marjorie even moved into Coronado Place, she read all the books about her. “There were rumors that she was moving here, and I went right out and checked them all out from the library,” she said.

That opened the door for what I thought was an obvious question: “Weren’t you afraid?”

“Oh no,” she said. “I judge people as they are, not how I heard they are. Everyone deserves a chance at redemption.”

“But the murders, the arsons?” I said.

“She’s only ever been kind to me,” she responded quickly. “Though I did have to sign the papers.”

I gave her a puzzled look, and she explained that Marjorie’s probation officers paid her a visit and explained, in painstaking detail, that a friendship with Marjorie could pose serious risks. “Then they had me sign a piece of paper that I understood,” she said.

I gaped at this, until the woman loudly summoned her frenetic white poodle.

“Well, I have to go,” she said. “I promised Maggie we’d go out for a walk. I will ask her to talk to you, but I don’t think she will. You can follow at a distance, if you want.”

I watched the woman move slowly to the center of the condo development with her white poodle wandering dangerously all around. Then, from Marjorie’s building, she came. This wasn’t at all the woman I saw the first day, with the angular face and the varicose veins. This woman was hunched and shuffling in a long, pink nightgown and matching robe, with white socks and blue plastic flip-flops. Slowly, very slowly, she pushed a rolling walker. The couple I had interviewed earlier had told me that she wanted to move into an Emeritus Senior Living facility in Tucson because she had so many health problems. When they told me that, I had taken it with a giant grain of salt; after all, health problems have traditionally been just another card Marjorie could play — with judges, with lawyers, with family — to get what she wants. But this looked like the real deal: She looked very thin and small, but unmistakably Marjorie, with her short dark hair slicked back, like a female version of Sen. Joe McCarthy. I watched Marjorie and Marjorie’s friend and the poodle work their way around the development until it was too dark to see.

In the morning, I made my last desperate attempt. I ruffled up all of my courage and rang Marjorie’s bell. She came briefly into view, still small and frail-looking, but now dressed in a crisp blue-checked shirt. “Hi, Marjorie,” I said quietly. She looked me square in the eye and said, “Please leave or I will call the police.” Then, just as quickly as she was there, she was gone.

I wondered what a steel-toed journalist would do. Camp out on her stoop? Make her call the police? I briefly wondered if I should write out a list of interview questions and tape it to her maroon-painted gate. It could be my Martin Luther-esque protest statement for all the reporters out there who have traveled more than 1,500 miles for an eight-word quote. I mumbled the questions to myself, like a crazy person:

“What was it like growing up in a mansion?”

“Do you have any regrets?”

“Have you ever felt really happy?”

“Which of your husbands was the love of your life?”

“Are you really a psychopath?”

I didn’t camp out, and I didn’t tape up a list of questions. I just walked back to my rented Kia, and I turned it toward the airport.