It wasn’t a cult — at least not at first. When Lavonne Christensen met Ron Johnson in early 1976, she instantly was taken with his mild demeanor, his passion for the word of God, his enthusiasm for even the smallest congregation. “He had a certain way,” she says. “He would stand on the edge of a room and let people come to him.”

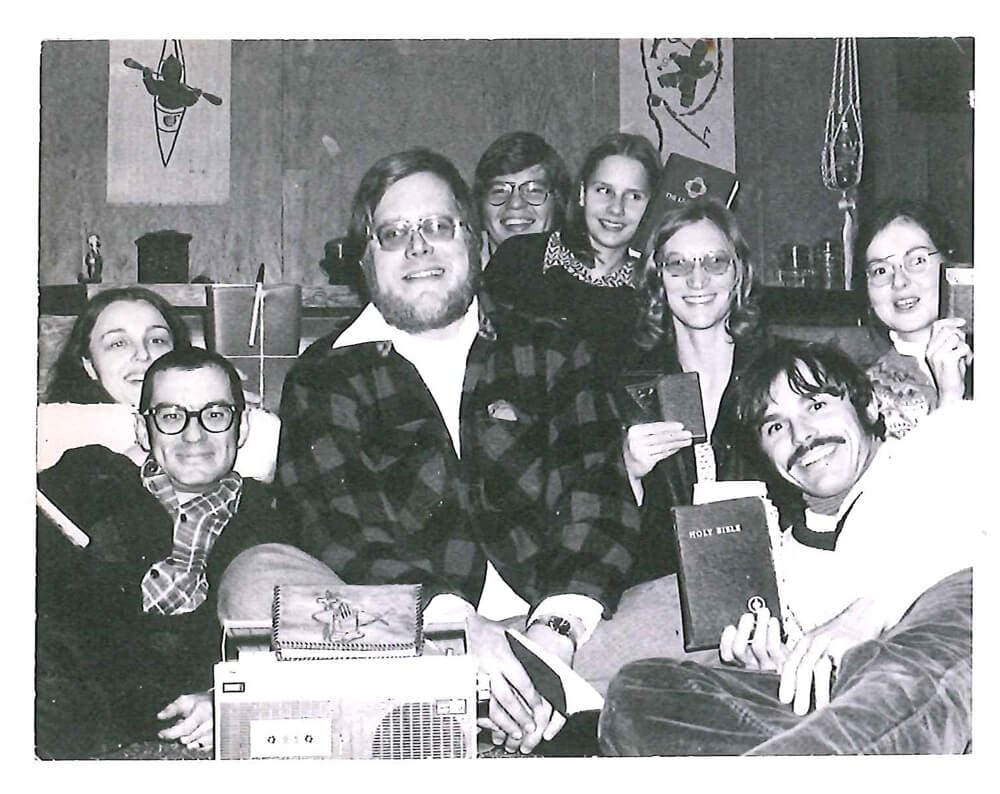

Johnson was a young preacher, eager to find a congregation of his own. In 1976, he was driving his wife and three young daughters four hours every Sunday from Aurora to Silver Bay to lead a gathering of eight people. At first, he preached in Christensen’s living room to four married couples, including her and her husband. “Right away, we were a very tight-knit group,” she says. The connection felt so real that the preacher and his wife even named their new baby girl Lavonne.

Within six months, there were more than 30 worshippers. People crowded shoulder to shoulder in the Christensens’ living room. The congregation started meeting in one classroom in Silver Bay, and then two. Then they held services at the Silver Bay Curling Club. By 1980, the church was attracting more than 300 people each Sunday — that in a town of just 3,000. The church members gave themselves a name: Scofield Bible. At its peak, the congregation met in one of the biggest buildings in town: the Union Hall.

“It was like a movement,” says Lauri Holman, an early member. “Everything seemed so tough in Silver Bay in the late seventies and early eighties. The mines weren’t doing well, and people were getting laid off. It was gloomy, and people were looking for something.”

Christensen was a force to be reckoned with. She estimates she saved some 100 people during a five-year period. “I’m a born saleswoman, and I had my pitch down cold,” she says.

But by 1980, Johnson had changed. “It’s hard to say when it happened, but definitely by the time hundreds of people started showing up, his demeanor changed, his preaching style changed,” says Holman. It wasn’t that he started sleeping around with the churchwomen or embezzling money. He wasn’t that kind of cult leader. But the preacher’s edicts quickly turned bizarre.

First, Johnson told his congregants to get rid of their TVs. Then he preached that the Bible was the only useful text and that all supplementary religious study guides should be burned. “It wasn’t just ‘throw them in the trash,’” recalls Christensen. “He told us to burn them.” Then the minister declared from his pulpit that all schoolchildren should be pulled from organized sports. Christensen pulled her daughter, Lisa, off the track team and no longer allowed her son Eric to play hockey.

“When all the kids got pulled off the sports teams, I think that’s when we got our reputation of being the weird church,” she says. Johnson had an undeniable magnetism, and church members started making displays of affection for their teacher. “One whole summer, a bunch of us remodeled his house,” says Holman.

Christensen started pulling away from her family. “I came to the opinion that my parents were just ‘playing church,’ that they weren’t real Christians,” she remembers. “I never said it to them, but I was certain they were going to hell.” Lisa worried constantly about the souls of her grandparents, teachers and other people she knew who were “out of fellowship.”

Johnson started grooming certain church members, especially women, calling them at all hours of the day and night. “He would call me and ask me check up on certain people, to keep my eye on certain people,” says Holman. “At first, I felt really special. When I would do good things, I would think to myself, ‘Wow, I wish Ron Johnson could see this.’”Even though Christensen was into the church — to the point of shunning her parents — she felt that the minister was wrong on one point. “He was preaching that Christians were always susceptible to Satan, but my belief was that once you were saved, the spirit of God guides you in the right direction,” she says. She talked to Johnson directly then made the cardinal error of discussing her view with a few other congregation members. Word quickly reached the preacher that she might be “falling out of fellowship” with all of her troublesome questions.

In 1981, Johnson unveiled a new threat during a sermon: Someone in the congregation was being used by Satan to destroy their new church. And then he preached it again. And again. And again. “That’s what I remember — the repetitiveness,” Christensen says. “He would talk about the wily ways of Satan and how he comes like a thief in the night. By the end of the year, I was absolutely sick with fear. Every Sunday, I looked around and I thought, Who is it? Who is it?”

Then, in the summer of 1982, Johnson revealed the identity of the evil interloper, she recalls: “He was up there preaching, and then he stops and looks at me and says, ‘Lavonne, can you say you’re not being used by Satan to destroy this church?’”

Christensen was confused. So confused that she didn’t even understand what had happened. It fell to one of the other churchwomen to break it down for her the next week, while their kids were swimming together. “It’s you, Lavonne,” she said. “He said that it’s you.”

In that moment, her world was shattered. “I just remember bawling so much, and saying, ‘It’s not me. It’s not me,’” remembers Christensen. But Johnson had spoken, and she was it, the one working in league with Satan to destroy their church.

Christensen was no longer invited to attend Bible study groups or weekly coffee klatches with the women from church. She still attended Sunday services, but she sat in the back of the room, physically separated from the other worshippers. They did not speak to her or visit her. Holman says that church members were made to understand that if anyone reached out to Christensen, they should report the whole exchange to Johnson right away.

She became so withdrawn and ashamed that she would no longer look in a mirror. “Every thought was like a minefield,” Christensen says. “I would think, Should I make dinner? Should I go to Duluth? And then in the next breath, I would think, Is that what Satan’s telling me to do?” All her life, she had been an extrovert, but now she dreaded even the most routine trips to the grocery store.

Christensen felt that she couldn’t reach out to her parents or siblings because she was still convinced that they did not have “truth.” She didn’t get help from her husband, who had stopped going to Scofield Bible around 1978 and was becoming more and more estranged from her. She couldn’t lean on any of her church friends, who were focusing all their efforts on her children, inviting them to special meet-ups and play dates. “There was an effort on the part of people in church to try to save my children from what they saw as a potentially damaging situation — that is, living with me,” says Christensen.

Lisa was 14 years old when her mother was first ostracized. She remembers being pulled aside by an older kid and told what was happening with her mother. “I don’t remember being afraid, really,” she says. “But I accepted it, absolutely. I completely revered Ron Johnson. To me, he walked on water. I bought into his whole thing hook, line and sinker.”

Some six months after she had been called out, Christensen decided to kill herself. “When I made the decision, I felt this wonderful wave of relief,” she remembers. “I was so happy to think that I didn’t have to deal with it anymore. But mostly, I felt that if I were gone, my children would have it so much better. I thought it was one final gift I could give them.”

Her youngest son, Thomas, was born about a month after Christensen was called out in church as Satan’s co-conspirator. When he was four months old, she decided to kill herself by filling the garage with exhaust from her car. She tucked her children into bed and put the baby in his crib. As she was leaving for the garage, Thomas started to fuss and wail, so she rocked him back to sleep. She tried to leave a second time, and he awoke again, fussing and crying.

“The third time it happened, I wrapped Thomas in a blanket, and I decided I was going to take him with me,” Christensen remembers. “I got outside with him, and I thought, What are you doing? You can’t kill your baby.” She decided she would wait until Thomas was asleep, but he never did settle down that night. “I really, honestly believe that if Thomas had just gone right to sleep that night, I would be dead,” she says.

Christensen attended Scofield Bible Church for three more years after that dark night. She knows how crazy it sounds, to continue attending a church that has very plainly ostracized you and driven you to the brink of suicide. “All I can say is that I really, truly believed,” Christensen says. “I believed that the only way I was going to conquer Satan was to keep going to church, to continue to seek help.”

She was ostracized from that church community until the very last day. She finally left in the summer of 1986, around the same time that she divorced her husband. Christensen was able to gather the courage to leave only after she had an affair with a man in the church, and even then she felt that she was not just leaving a church in Silver Bay, but God himself. “By the end of that three years, I was so starved for human contact, it was like bread and water to me,” she says. Christensen reconciled with her family, moved in with her sister and got her very first job at age 38: a paper route. She says it took a good 10 years to fully deprogram from her experience with Johnson and his church.

Today, Christensen has a successful real-estate business in Two Harbors and takes a certain pride in holding her head high in Silver Bay. “I can talk to anyone in Silver Bay, even though I know there are people in town, even 30 years later, who think I might be somewhat evil,” she notes.

Ron Johnson is still a preacher in Silver Bay. His congregation consists of about 10 people. He no longer uses the Scofield Bible Church name; they call themselves the Lakeside Bible Church. In 1988, he sent Christensen a letter apologizing for his actions. To this day, they still have never spoken about what happened more than 30 years ago in that little town on the North Shore of Minnesota.

Read this article as it appears in the magazine.