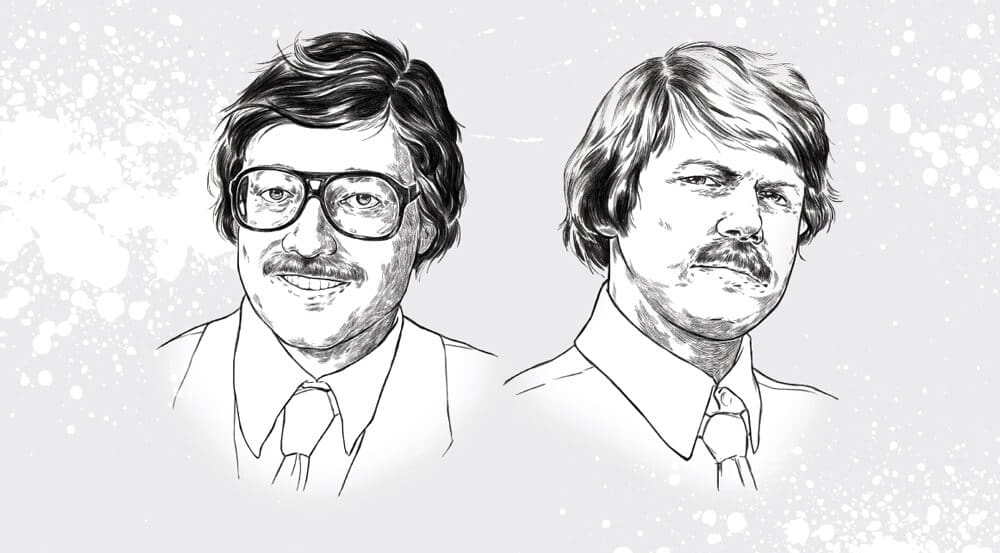

John DeSanto and Gary Waller were in their early thirties when they were named chief prosecutor and lead investigator, respectively, for the Glensheen murder case. They didn’t know it at the time, but Minnesota’s most infamous crime would singularly shape their careers and inextricably weave their lives together. They spent years working alongside each other, eventually penning the book Will to Murder about their experiences. Artful Living had the distinct privilege of sitting down with these lifelong friends to hear their crystal-clear memories of how it all unfolded, to learn what they wish had gone differently and to witness the raw emotion that, to this day, still sits just below the surface.

Artful Living: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you get involved with this case?

Gary Waller: I came home from jogging — I was jogging every day when I was younger — and the phone rang. One of the other detectives said, “The boss wants you down at Glensheen right away.” Well, I don’t know where Glensheen is at; John and I were raised in working families. So, he said to me, “3300 London Road. There’s a double homicide down here. Elisabeth Congdon and her night nurse, Velma Pietila.” I had heard of Congdon Boulevard, Congdon Creek, you know, because they were one of the five wealthy families in Duluth.

I went down there and looked at the crime scene. Velma was on the stairway, and she had 23 lacerations in her head, some of them fracturing her skull. And Elisabeth had a pillow over her face; she had been smothered.

John DeSanto: Here’s my memory of it: In 1976, at age 29, I was appointed chief prosecutor for St. Louis County. I was way too young and inexperienced for this promotion, but I was the most experienced prosecutor in the St. Louis County Attorney’s Office, with only three years’ experience, and I’d tried five murder cases before the Glensheen murders.

So as chief prosecutor, I get the call from the police department: “There’s a double homicide at Glensheen.” Like Gary, I’d never been there. I shouldn’t have been at the scene, but I wanted to see it all, too. And I did take pride in the fact that I’d been at the scene before the bodies left and I could put that in my mind’s eye for later at trial.

AL: When did you first meet Marjorie and Roger?

GW: First, I met Dave [Arnold], their attorney. They came to the police department to see my boss, Ernie [Grams], and me. Marjorie, as soon as she got there, she started talking. And I could tell Dave was pissed. Beforehand he had told us, “I told her to keep her mouth shut, so don’t expect her to say anything.”

AL: What was your first impression of her?

GW: I’ll tell you what: She had a lot of boyfriends, and it wasn’t because she was attractive. I was looking at Roger, and he had a cut on his lip, he had a cut on a finger and his right hand was really swollen. I remembered Velma had been punched in the face before she was beaten up with the candlestick holder. So, when they got up to leave, I shook Roger’s hand, because I wanted to feel it — and he winced. I’d been in the autopsies, and I figured he had punched her.

I was at Glensheen later that afternoon, the day before Elisabeth’s funeral. BCA [Bureau of Criminal Apprehension] came up to finish processing the crime scene. Marjorie came up, and I said, “You can’t come in here.” “Well, why not?” I said, “You can’t. Nobody can — just the cops.” Then she kind of hit on me, and I thought, “You must be out of your mind.” I had more respect for myself than that.

JD: My first in-person encounter with Marj really wasn’t until she was arraigned in court more than a year later. But I remember about a month and a half after the murders she was on the front page of the Duluth News Tribune with a bandage over her face. She cut herself and claimed that Gary did it.

GW: Yeah, not by name.

JD: No, not by name. Described you, right?

GW: Described me to a T.

JD: The first time I’m seeing who Marjorie is was with her bandaged face on the front page of the Duluth newspaper, and I’m thinking, “Whoa, this is going to be something.”

I first see Roger at his arraignment in St. Louis County Court in Duluth. He’s charged with two counts of murder, first degree. And to be honest with you, I recall thinking, “This guy did it?”

And at Marjorie’s trial [in Hastings in 1979], I’ve got this vivid memory that one day she shows up in a bright yellow pantsuit, and I’m thinking —

GW: Looked like a big canary.

JD: You took the words out of my mouth. She looked like a canary.

GW: I told you, she wasn’t that pleasing to look at.

JD: And I’m thinking to myself, “This is weird what she’s wearing to court; she’s charged with murder!”

AL: What bizarre moments do you recall from the investigations and trials?

JD: Here’s one of the most flabbergasting moments from Marjorie’s trial. One day in May of 1979 — more than one month into her trial — it’s her attorney, Ron Meshbesher’s birthday, and she shows up with a cake. She wants everybody to have a piece: “Well, you’ll have a piece, Gary and John,” she says to us. And we had already been telling Ron —

GW: Keep her away from us.

JD: We don’t want to talk to her. We don’t want her talking to us. And she asks, “You’ll have a piece, won’t you, John?” And I say, “You’ve got to be kidding.” And her terse, unbelievable statement was, “Don’t worry; there’s no marmalade in it.”

GW: And then there’s the incident between Roger and [his attorney] Doug [Thomson] during Roger’s trial. We found out that Roger had a coin collection. Well, after we gave Doug that information, Doug takes him into a closet — literally in the closet — outside the judge’s chambers, and he’s yelling at him in there.

JD: Yelling at him.

GW: Oh, yelling.

JD: “You didn’t tell me anything [about owning a coin collection]! You don’t —”

GW: “Goddamn it.”

JD: “You should have told me. Why did you never tell me you had a coin collection?” Because that gave us a reason for Roger to send the [stolen] coin to himself.

GW: In 2003, we got Roger’s DNA off the seal of the envelope [that contained the stolen coin]. Back then, on the envelope, we had an expert testify that it was his handwriting on the outside of the envelope. And Golden — he spelled it with a small G and a capitalized A corrected to an O.

So I got a search warrant to get Roger’s briefcase from his lawyer’s office. I’m going through all this crap in his briefcase, and I find where he’d made the same mistake writing “Golden.”

JD: It was so telltale. That was absolutely his handwriting.

AL: Was Roger just a puppet in all this? Or was he an active participant?

GW: He was a drunk.

JD: Dimwitted drunk. He had a history of alcohol, and he got set up by Marj. I firmly believe that to this day.

AL: If this case were taking place today, how would things be handled differently?

JD: Well, first and foremost, we’d have DNA. We would be able to say that the blood found at the crime scene was Roger’s with 99.999% certainty.

And the fingerprint that went bad? That wouldn’t have mattered. It wouldn’t have reversed Roger’s conviction, and he’d still be in prison.

Here’s the story: Gary’s out in Colorado and finds the envelope with the [stolen] coin. And ultimately, there’s a latent print developed by Colorado Bureau of Investigation. And I think, “We just won the case.” This was back when latent prints were the DNA — they were irrefutable, basically. Well, Gary had told me [back then] that, in his opinion, looking at the comparison of the latent print versus the real or known print of Roger that the latent was too fuzzy.

GW: I told him not to use it.

JD: I got all the way through Roger’s trial with it. So I did get overconfident. We’d convicted Roger, so I thought, “We can convict Marjorie, too, using the same fingerprint evidence.” In retrospect, it was a completely different case, with her charged as Roger’s coconspirator and her not being at the murder scene.

GW: And then there’s the theft of Roger’s wallet from the property room in the Hastings courthouse just before we were going to introduce it into evidence during the testimony of Sergeant Jack Greene. Roger’s wallet contained stamps identical to the stamps on the envelope containing the stolen coin mailed from Duluth to Roger on the day of the murders.

JD: The BCA lab could not physically match the stamps in the wallet to the stamps on the mailed envelope, but —

GW: They were the same type of stamps.

JD: Identical. And that was so critical to us. And then the wallet gets stolen out from under us following defense attorney Frank Berman being inside the property room [where the wallet was] alone.

See, we had an agreement: If the defense wanted to see something in the property room, they wouldn’t go in to see the physical item without a prosecutor there, and vice versa — we couldn’t go into the property room without a defense representative there. So my second chair [then-Assistant County Attorney Mark Rubin] goes in there with the defense, and they take a look at the wallet again. After they leave, a clerk comes and tells me, “Berman was in that property room alone.”

We go back there, and we can’t find the wallet. So I tell the judge, “Judge, we can’t proceed. We need to find this wallet. It’s a critical piece of evidence.” He says, “You’ve got 15 minutes to look for that, and then we’re getting going. I don’t want a delay.”

GW: You forgot a part. Carol Grant was third chair for the defense, and she had this big lawyer briefcase. So she’s ready to go for the day, and she takes her briefcase and heads out to her car.

JD: You ask what I would have done differently? I would have shut down the trial. If I had a little more savvy, a little more experience, a little more guts —

GW: And if the judge had any [guts].

JW: I would have gotten a search warrant, and I would have looked at all their briefcases.

AL: Did the wallet ever turn up?

JD: It never turned up. We lost that piece of evidence.

AL: Was there a point in Marj’s trial when you realized things were going south?

JD: Here’s when we realized it was going south. Late in Marjorie’s trial, in the defense case, Ron [Meshbesher] calls Herbert MacDonnell, who is an interesting character himself. He’s a —

GW: The best expert one can buy.

JD: Yeah, he’s what they called a criminalist, who does everything — paint matching, latent prints. And coincidentally, years later, he testified for the defense in O.J. Simpson’s case.

MacDonnell testifies, “This is not Roger’s print.” So after court, Gary and I are saying, “We need a third expert.”

GW: So I called Quantico and asked, “Do you have any witnesses that could testify for us at a murder case?” They say, “Yup; he recently retired.” What was his name?

JD: George Bonebrake — preeminently qualified.

GW: Head of the FBI latent-print division, recently retired.

JD: He comes in and says, “Give me a few hours on my own down in the basement,” where we had our office set up. We’re up in the kitchen, thinking he’s going to tell us that this is definitely Roger’s print. He comes up and says, “It’s not Roger’s print.”

So, here’s what I have to do. Now I have what’s called exculpatory evidence; it exonerates rather than incriminates. So I disclose it the next morning. I say, “Here, Ron.” And he is ecstatic. And then who shows up on the witness stand for the defense the next day? Bonebrake. It was gut-wrenching.

I was so devastated that I presented, albeit unintentionally, false evidence that ultimately resulted in Roger’s convictions being overturned. I was really emotional, and Gary was trying to encourage me: “Don’t worry; we’ve got enough other evidence.” And we walked the dark streets of Hastings at midnight, and I was sobbing. I said, “How could I do this? How could I do this? We’ve lost the case.”

We had Roger with the stolen jewelry. We had his blood at the crime scene and his hair there, too. But the fingerprint was the coup de grâce. The Minnesota Supreme Court said it couldn’t allow a conviction to stand on evidence that included a misidentified fingerprint.

I should have done more. I should have done more. I should have looked at that print again. There’s no question in my mind that we could have convicted Marj if I’d done some things differently — argued it better, etc. That said, I don’t think we did a bad job.

AL: How did this case shape your careers and your lives as a whole?

JD: I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything in the world, as hard of work as it was. It was the ultimate circumstantial evidence case — the type of cases I wanted to try and was blessed to try for 35 years — and it happened six years into my career. My career became known as BC and AC: Before Caldwell and After Caldwell.

GW: And we were devils to work for after we had experienced this.

JD: We had learned from our mistakes in the investigations and prosecutions of Roger and Marjorie Caldwell from two of the best criminal-defense attorneys the state of Minnesota has ever seen — and we made sure we didn’t make those mistakes again!

Read this article as it appears in the magazine.